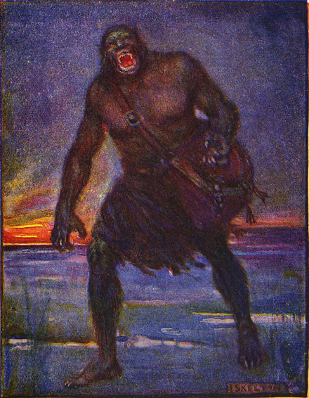

Of all the horrifying scenes, which activate what Michael Lapidge has termed the psychology of terror in Beowulf,[1] none are more terrifying than the scene of Grendel’s approach from the night, through the marsh and to the hall. Translations and adaptations of Beowulf approach Grendel in a variety of ways—from emphasizing his monsterization as a eoten “giant” (761) and þyrs “troll” (426) to more humanizing treatments that focus on his status as a wonsaeli wer “unfortunate man” (105).

This Halloween, in continuing our series on Monsters & Magic, I offer a translation and recitation of the monster’s haunting journey to Heorot. This scene has been well-treated in the scholarship, and Katherine O’ Brien O’Keeffe has noted that once the monster finally enters the hall, there is a potential “horror of recognition” by the audience who is then able to identify Grendel as human.[2]

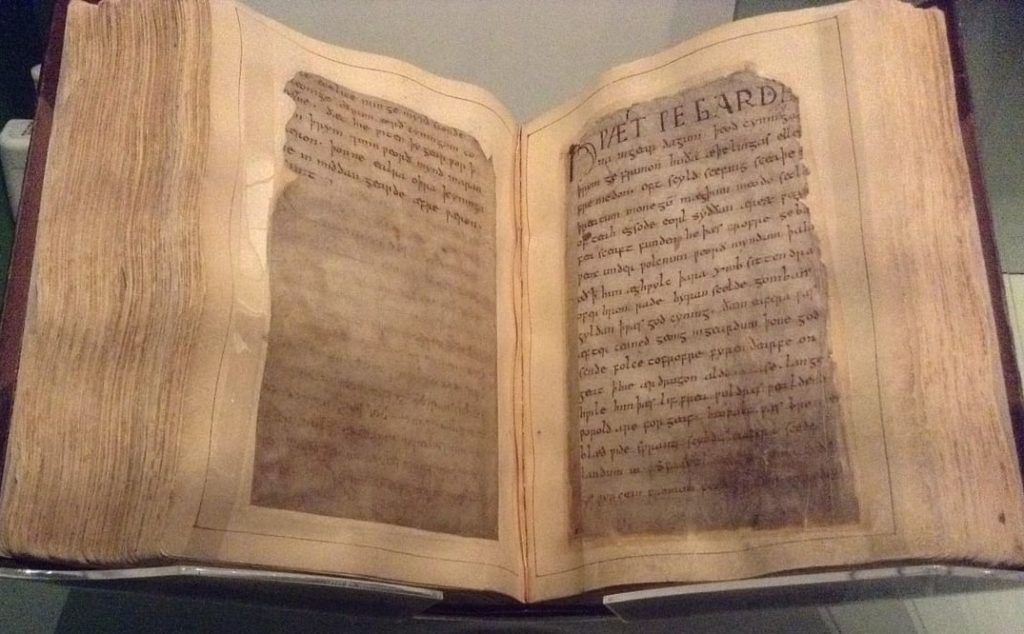

This blog will focus closely on the Old English poetic language and how Grendel shape-shifts as he draws nearer to Heorot, seemingly coming ever better into focus and transforming to match the space in which he inhabits. I will consider three major sections of his approach, signaled by the thrice repeated verb com “he came” (703, 710, 720), and I will reflect on the ways in which Grendel is described in each leg of his journey.

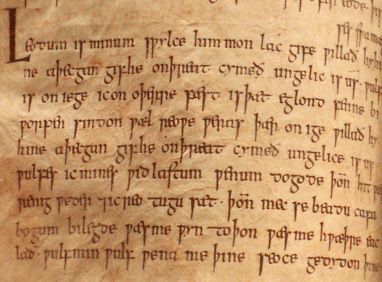

In the first passage, Grendel com on wanre niht “came in the dark night” (702), and he is characterized as sceadugenga “shadow-walker” (703): either a “going shadow” or “one who goes in the shadows” (both at available options based on the poetic compound). His movement is described as scriðan “slithering” or “gliding” (703), further emphasizing his portrayal as a shadow monster. Later, when Grendel is named a synscaða: either a “relentless” or a “sinful ravager” (707), depending on how one interprets the polysemous Old English syn in the compound,[3] the monster is described as pulling men under shadow, characterizing Grendel as a night terror shrouded in darkness. Indeed, when Grendel comes from the dark night, he is represented by the narrator as a shadow monster that hunts and haunts after sundown.

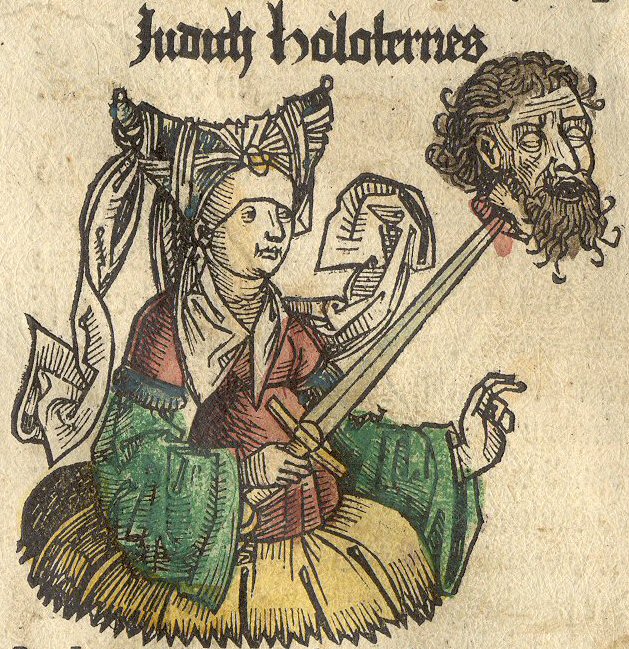

In the second passage, when Grendel ða com of more under misthleoþum “then came from the marsh under misty-slopes” (710), the monster emerges from the swamp and is addressed by his name: Grendel (711). I imagine the silhouette of the monster taking shape in the mist—perhaps a human shape—corresponding to his characterization as manscaða, which likewise plays on polysemous Old English man in the compound, (either mān meaning “criminal” or man meaning “human”).[4] The alliteration in line 712 seems to stress the possibility of monstrous manscaða as “ravager of humans” or a “human-shaped ravager” since manscaða alliterates with the monster’s intended prey, manna cynn “the kin of humans” or “mankind” (712).

The mist rising from the marsh continues to obscure the audience’s view as Grendel wod under wolcnum “went under the cloud” (714) maintaining the suspense generated in the scene by suspending knowledge of Grendel’s ontology. Nevertheless, in this second leg of his journey, Grendel’s form seems to come into focus as he shifts from sceadugenga “a shadow-walker” (703) into manscaða “a mean, man-shaped, ravager of men” (712).

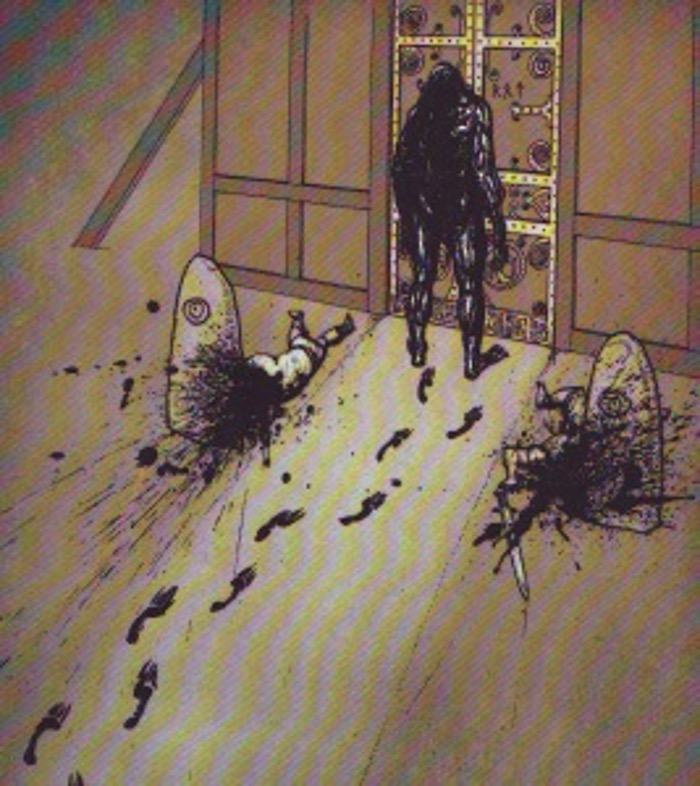

In the third passage, Grendel finally arrived at the hall and the audience learns at long last what Grendel is: rinc dreamum bedæled “many bereft of joy” (720-21). During the last leg of his journey, Grendel’s humanity is laid bare leading to the ultimate realization identified by O’Brien O’Keeffe, when Beowulf appears to recognize Grendel’s humanity after the monster bursts open the door of the hall.

Throughout the next twenty lines, in addition to Grendel (720), the term rinc “human warrior” is repeated: twice in reference to the Geatish troop as a whole (728, 730), once in reference to the sleeping man Grendel cannibalizes when he arrives, who the audience later learns is Hondscio (741), and once in reference to Beowulf himself (747). This repeated use of rinc “human warrior” highlights how Grendel is a mirror for the hero and the Geatish warriors, characterized in identical terms.

Similarly, when Grendel approaches from the shadows, Beowulf is described as bolgenmod “swollen-minded” and angrily awaiting battle (709); however, once the monster arrives at the hall, Grendel becomes gebolgen “swollen (with rage)” as he enters the hall ready to glut himself upon the men sleeping inside (723). This parallel description interweaves the respective emotions and behaviors of both hero and monster in Beowulf.

The interplay between hero and monster continues when Beowulf and Grendel struggle together, both called reþe renweardas “ferocious hall-guardians (770) and heaðodeore “battle-brave ones” (772) during their epic battle that nearly destroys the hall. The fusion of hero and monster together into a shared plural subject and object respectively helps to underscore their mutual affinity: the hall must contend against the fury of both warriors and each is a fearsome—yet overconfident—conqueror, who intends to overcome any enemy he encounters.

We know that this is Grendel’s final chance to haunt the hall, and the monster is at least able to feast on one last human, this time a Geat and one of Beowulf’s own warriors (Hondscio). Sadly for Grendel, once Beowulf finally decides to enter the fray, and after a relatively brief struggle, the monster is fatally disarmed and retreats to die at home in the marshes.

Naturally, vengeance follows. Unfortunately for the Danes, and especially Hroðgar’s best thane Æschere, the audience soon learns that Grendel has a mommy, and anyone who messes with her baby boy, will have to answer to her.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading:

Brodeur, Arthur G. The Art of Beowulf. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1959.

Fahey, Richard. “Medieval Trolls: Monsters from Scandinavian Myth and Legend.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (March 20, 2020).

—. “Enigmatic Design & Psychomachic Monstrosity in Beowulf.” University of Notre Dame: Dissertation, 2020.

—. “Mearcstapan: Monsters Across the Border.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (July 20, 2018).

Gwara, Scott. Heroic Identity in the World of Beowulf. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Johansen, J. G. “Grendel the Brave? Beowulf, Line 834.” English Studies 63 (1982): 193-97.

Joy, Eileen, Mary K. Ramsey, and Bruce D. Gilchrist, editors. The Postmodern Beowulf: A Critical Casebook. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press, 2006.

Kim, Dorothy. “The Question of Race in Beowulf.” JSTOR Daily (September 25, 2019).

Köberl, Johann. The Indeterminacy of Beowulf. Lanham, MD: University of America Press, 2002.

Lapidge, Michael. “Beowulf and the Psychology of Terror.” In Heroic Poetry in the Anglo-Saxon Period: Studies in Honor of Jess B. Bessinger, edited by Helen Damico and John Leyerle, Studies in Medieval Culture 32, 373-402. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 1993.

O’Brien O’Keeffe, Katherine. “Beowulf, Lines 702b-836: Transformations and the Limits of the Human.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 23.4 (1981): 484-94.

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Sharma, Manish. “Metalepsis and Monstrosity: The Boundaries of Narrative in Beowulf.” Studies in Philology 102 (2005): 247-79.

Ringler, Richard N. “Him Sēo Wēn Gelēah: The Design for Irony in Grendel’s Last Visit to Heorot.” Speculum 41.1 (1966): 49-67.

[1] Michael Lapidge, “Beowulf and the Psychology of Terror,” 373-402.

[2] Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, “Transformations and the Limits of the Human,” 492.

[3] Andy Orchard raises the possibility of polysemy in synscaða, see Pride and Prodigies, 38.

[4] Orchard also raises the possibility of polysemy in manscaða, see Pride and Prodigies, 31.