In translating and reciting Deor, I took more artistic liberties than in previous translations of Old English poetry. Because the translation and recitation are their own discrete projects, I will discuss each separately, beginning with my translation.

Translation: “Deor’s Dark Elegies” by Richard Fahey

Tackling a translation of the anonymously titled Old English poem editors refer to as Deor, I chose to focus on a few features that mark this poem as unique in the corpus—especially the episodic structure and the operative elegiac mood of the piece.

In my translation “Deor’s Dark Elegies” I have adapted the structure of the poem, dividing each stanza both by a title and a refrain to emphasize the episodic quality of this particular Exeter poem, rather than simply the refrain. This required me to morph the syntax in places in service of enhancing the episodic structure of the piece.

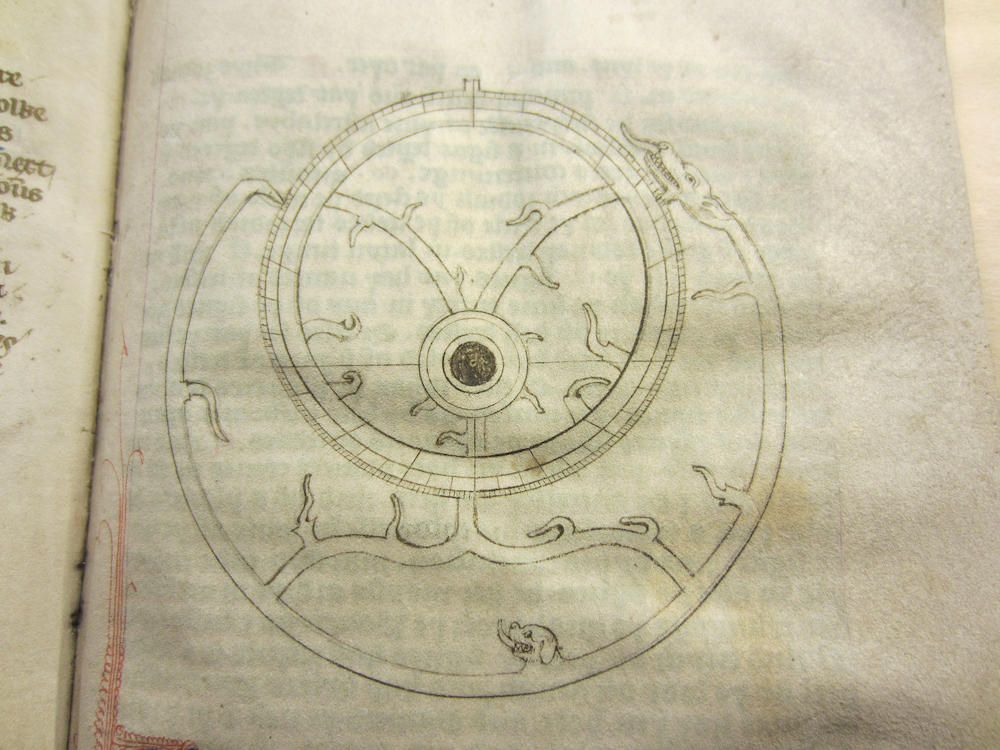

Unlike the one other poem considered ‘heroic’ in the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501), editorially titled Widsith—which is more of a list of heroes and peoples—Deor alludes to numerous legends, usually focusing on the tragedy befallen the tale’s protagonist. In a sense, Deor represents a series of subnarratives—a catalogue of heroic experience and existential crises, met ultimately with the grim realization that all earthly things fade into obscurity under the unrelenting passage of time. So proclaims the refrain: that passed away, may this too.

Fatalism is generally considered to be a familiar, even indigenous, concept for the pre-Christianized Scandinavian and Germanic peoples, it could alternatively be argued that the philosophy articulated in Deor may be drawn from the theology of Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae, which is translated by King Alfred into Old English before the compilation of the Exeter Book and remained intellectually influential in medieval England, eventually inspiring the famous Geoffrey Chaucer to produce Boece, a translation of the text, over three hundred years later.

Deor employs what might be described as an ‘elegiac mode’ operating in other Exeter Book poems as the narrator reflects on the transitory nature of human existence. In this way it reminds the reader of other so-called Old English elegies in the Exeter Book, such as The Wanderer (which Seamus Heaney translates and recites as does our own Maj-Britt Frenze) and The Seafarer (which Ezra Pound translates and recites) that likewise reflect on transitory life, but imply the final Christian consolation of heaven in line with Boethius and notably absent in Deor. Instead, a somber tone—pervasive throughout Deor—is one of the poem’s signature features. Therefore, in translating Deor, I attempt to preserve both the elegiac tone of lamentation and hardship as well as the darkening mood, which swells ultimately to include also the narrator, his own darkening days and personal tale of suffering and sorrow.

Recitation and Creative Adaption: Deor

Having collaborated with my twin brother, Boston sound artist and producer Thomas Fahey, my Deor ‘recitation’ became more of a sound art piece than a proper recitation of an Old English poem. The slow, methodic reading of the Old English alliterative meter and alludes to the tradition of Old English recitation, exemplified by Ezra Pound’s recitation of his Seafarer and intellectually grounded by the work of scholars such as Albert Lord and Miles J. Foley.

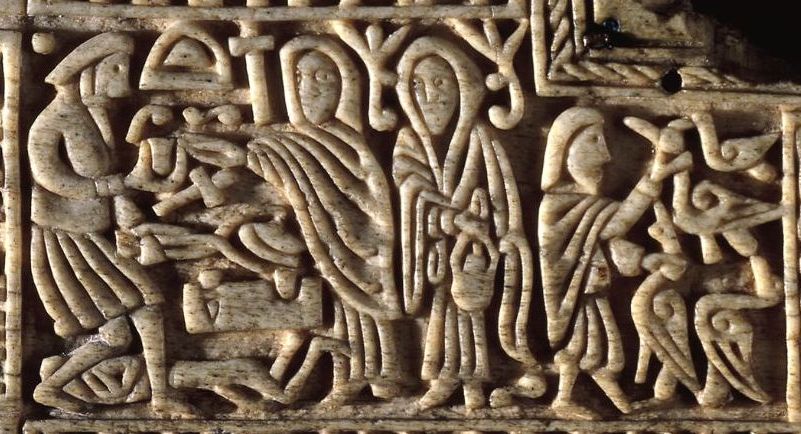

Nevertheless, many of the features emphasized in my translation were used to inspire the audio piece. As with the translation, structure and mood were organizing principles of the project. We placed emphasis on the refrain, and complemented the recitation of the Old English with samples and effects that create a shifting aural landscape—evoking the sound of an anvil-stroke, ravens, wolves, horses galloping, a woman moaning and a child crying—all of which corresponds with haunting imagery from various episodes of the poem.

While composing Deor, I decided I would expand the project and approach other recitations of Old English poetry in similar fashion in my future work. For this reason especially, any comments or feedback would be most welcomed and appreciated!

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame