by Julia A. Schneider, Ph.D, Medieval Studies Librarian

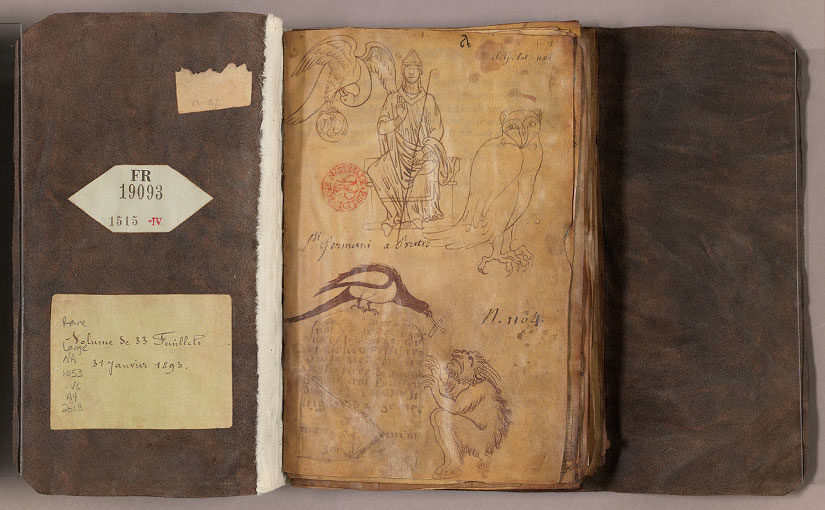

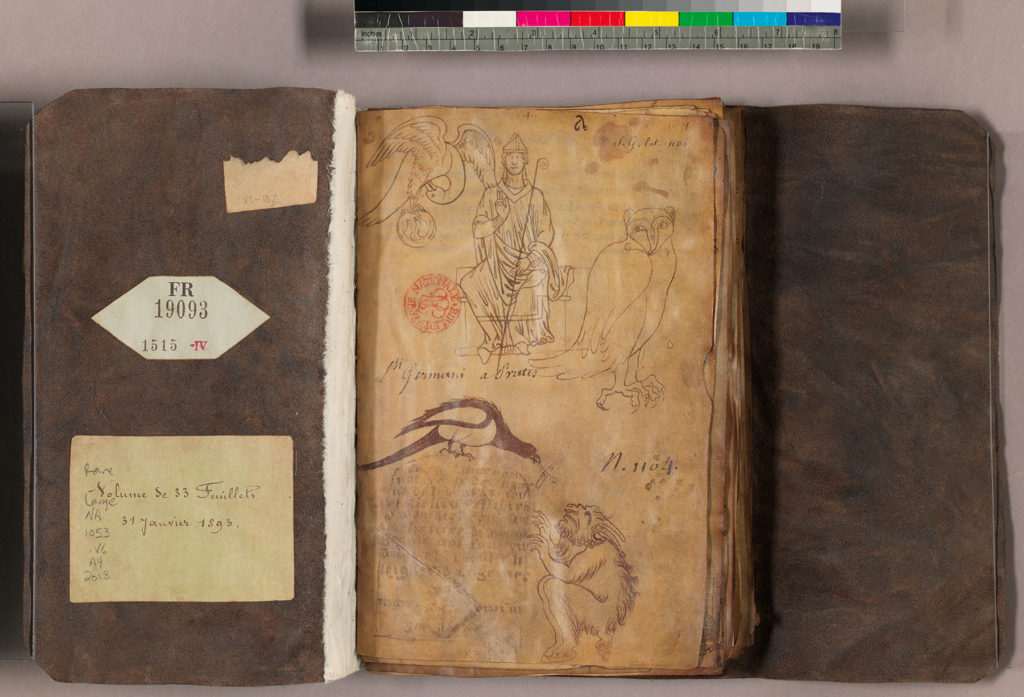

Any questions about the thirteenth-century French artist and architect Villard de Honnecourt and his work must be answered by the one portfolio of sketches and notes he left behind, or not at all: it is the only known example of his work. The original manuscript of the portfolio, which contains more than two hundred drawings on thirty-three leaves of parchment, was produced sometime between 1220-1240. Although almost all of the notes and drawings appear to have been made by the author, a few have been added or altered by subsequent owners. It came to the library at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Germain-des-Prés at the beginning of the eighteenth century, surviving a fire there. At the end of 1795 or beginning of 1796, it was taken to the Bibliothèque imperiale (now the Bibliothèque Nationale de France) in Paris, and there it remains under the shelfmark Ms Fr. 19093, entitled Album dessins et croquis (Album of drawings and sketches). 1

The Hesburgh Libraries recently acquired an original-format facsimile of this medieval treasure, published in 2018 under the title Cuaderno de Bocetos de Villard de Honnecourt de la Biblioteca Nacional de Francia, Ms Fr 19093, by Siloé Arte y Bibliofilia in Burgos, Spain (with an additional commentary volume forthcoming). Several other print facsimiles of this interesting collection of drawings have been made before, but none manage to show the original context of the drawings and artist’s notes in the same way that the original-format facsimile does. Because they provide real context, including the size, feel, and content of the ancient and medieval books that they copy, original-format facsimiles open the contents of books, book production, and intellectual history—the treasures of our past—to students in a new way.

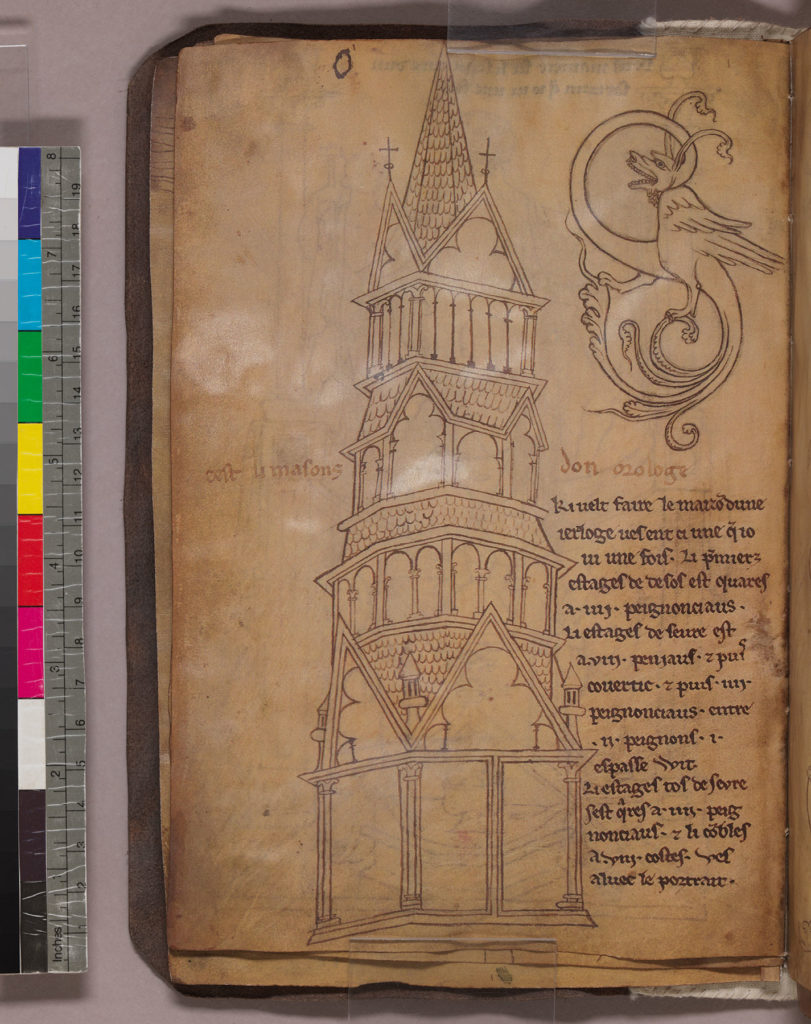

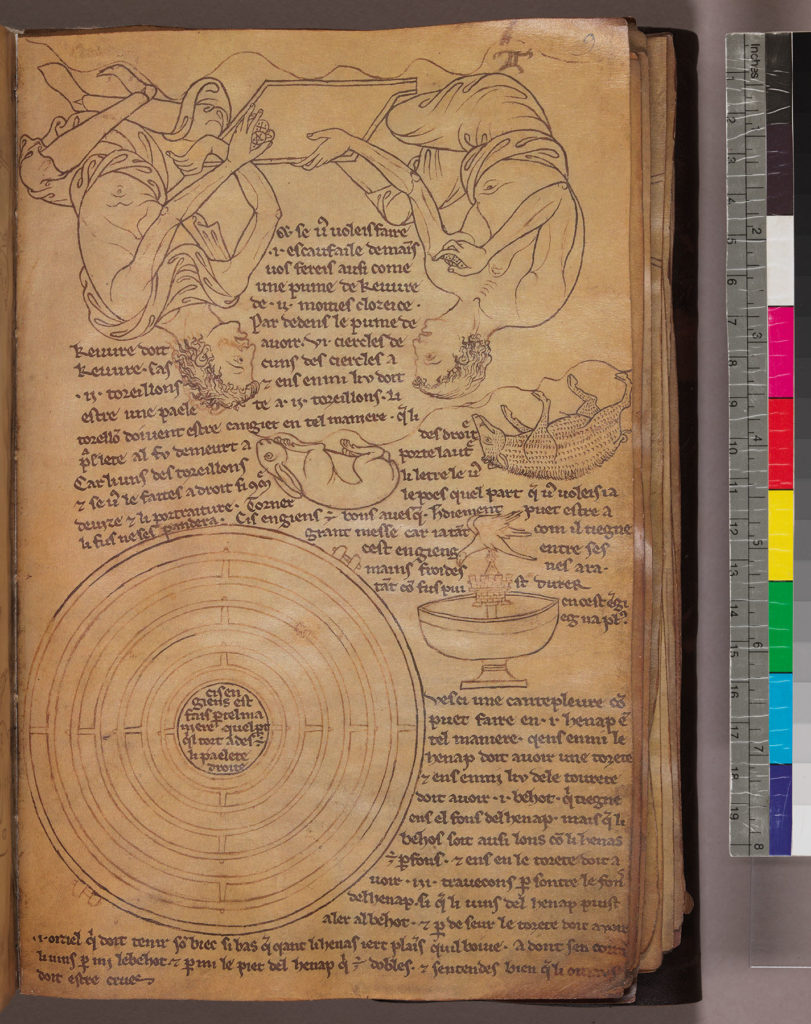

This facsimile is no exception in terms of offering us a glimpse into the world and thoughts of an itinerant artist. The notes within the portfolio, written in the Picardy dialect of Old French, tell us that he has traveled extensively; the included drawings indicate his interest in a wide variety of subjects, from extremely detailed gothic church architectural elements to mechanical plans, from stylized depictions of the Crucifixion to images of humans in a variety of naturalistic poses, animals, and insects, some with geometric underlay as part of their form. The way that they are put together also gives us an understanding of the life of the owner: the portfolio is made up of parchment leaves gathered from multiple sources of differing quality and sizes, sewn loosely together and bound in “a pigskin folder… a suitable size for slipping into one’s garments when traveling on horseback.” 2

For more on Villard de Honnecourt and his work, see:

Barnes, Carl F., Jr and The Bibliothèque National de France. The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt : A New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Fr 19093) with a Glossary by Stacey L. Hahn. Burlington, VT.: Ashgate, 2009.

Barnes, Carl F., Villard de Honnecourt—the Artist and his Drawings: a Critical Bibliography. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1982.

Footnotes

1. Barnes, Carl F. Jr. and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt: a New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Fr 19093) with a Glossary by Stacey L. Hahn (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 3.

2. Ibid., 3-4.