It will probably come as a surprise that August is ‘Spinal Muscular Atrophy Month’. However, you might be aware that April is National Poetry month, June LGBT pride month, and September Childhood Cancer Awareness month. Our long list of commemorative months, each designed to weigh on national thought, strongly gives the impression that months have allegorical meaning and that we should shape our daily lives according to them. One might say the Middle Ages had its own version of this phenomenon, as people routinely looked to the order of the natural world for spiritual guidance and direction. The Labors of the Month were hugely popular pictorial representations of certain agricultural duties for each month, like you see here. They are found throughout the Middle Ages in architecture, sculpture, stained glass, and books. Books of Hours, a very popular type of book in the Middle Ages containing prayers to be said throughout the day, frequently exhibited the Labors of the Month in their calendars.

The Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, 2nd half of the 14th century; London, British Library, Egerton MS 3277., f. 2r

The Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, 2nd half of the 14th century; London, British Library, Egerton MS 3277., f. 2r

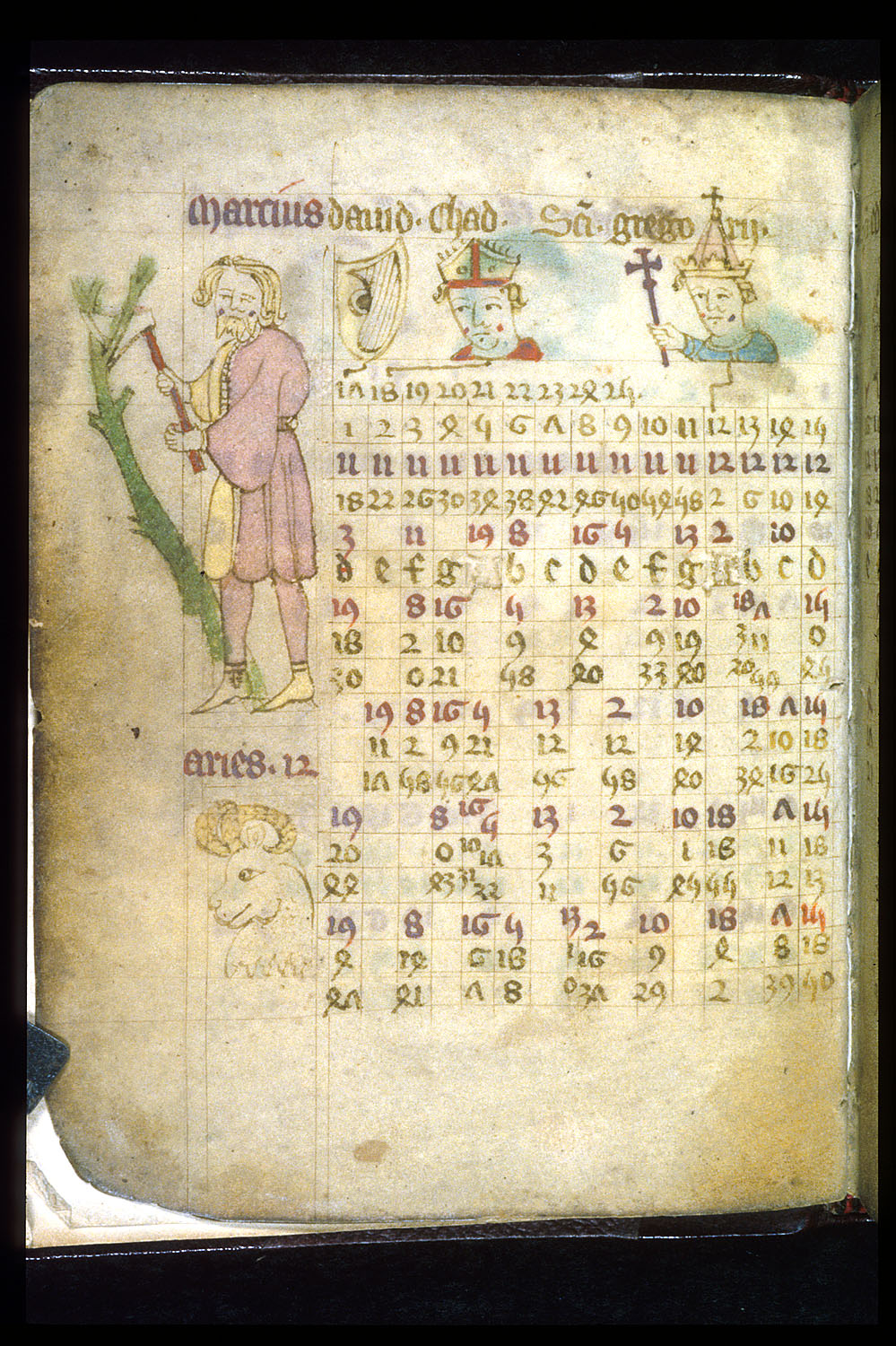

Almanac, England, 1st quarter of the 15th century; London, BL Harley MS 2332, f. 3v

Queen Mary Psalter, England, 1310-1320; London, BL Royal MS 2 B VII, f. 73v

Though all from the same country from the 14th-15th centuries, the images above show distinct designs for the month of March. In the Labors of the Months, March was generally represented by men pruning vines for the coming spring (Hourihane 2007: lvi). In Egerton 3277, the image is actually placed inside the initials KL for ‘Kalendas’, making it a so-called ‘inhabited initial’, as the image ‘inhabits’ the letters. The images in Harley 2332 and Royal 2 B VII, however, take up a large portion of the page. Unlike many medieval Labor scenes, each of the three presented here focus on the action of pruning, not the landscape in which it occurred. This suggests that the featured vine-pruning bears reflective, allegorical significance and that this image is not simply an artful representation of agricultural life. In fact, as scholar Matthew Reeve has noted, these types of images likely stressed the coming ‘perpetual religious service in the vineyards of the Lord’ (2008: 130). Some literary works of the period like Piers Plowman might even indicate knowledge of the meaningfulness attached to such labors.

It is important to remember that Books of Hours were not for the farmer or vine-trimmer. Rather, they were a privileged possession for those wealthy enough to even own a book, let alone one ornately decorated. If not for religious contemplation, then, it is of some wonder why the upper classes were so fascinated with images of backbreaking agricultural labor.

So, the next time you are informed that July is National Ice Cream month, know that here ice-cream stands on the shoulders of vine-pruners, and that humanity’s penchant for iconic monthly guidance is a long-standing tradition and probably here to stay.

Axton Crolley

Ph.D. Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of an ongoing series on Multimedia Reading Practices and Marginalia: Medieval and Early Modern

See also:

Hourihane, C., Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months & Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art (Princeton UP, 2007)

Reeve, M., Thirteenth-Century Wall Painting of Salisbury Cathedral (Boydell, 2008)