Today, we talk about dragons. I refer specifically to the greedy, northern (often fire-breathing) variety as described in Beowulf and featured in Tolkien’s Hobbit, and I will consider how these monsters present environmental catastrophe as a direct result of hoarding and greed.

My discussion of dragons and climate change continues my recent series of blogs interested in placing medieval literature (and in this case also modern medievalism) in conversation with current crises. This blog develops an earlier argument made in a paper at a “Tolkien in Vermont” conference (2014), titled “Dragonomics: Smaug and Pollution on Middle-Earth,” in which I argue that pollution in Tolkien’s Hobbit is linked to both the literal destruction by the dragon, and the rampant greed that motivates Smaug and ultimately initiates the plunder and violence at the Battle of Five Armies.

In the past, I have defined dragonomics as “the relationship between greed and catastrophe characteristic of certain representations of medieval dragons (especially the Beowulf-dragon),” which I separately argued also may apply to the study of Smaug in Tolkien’s Hobbit. In Beowulf, both the draca “dragon” slain by Sigemund (892), and the draca slain by Beowulf (2211), are depicted as excessively greedy, possessing heaps of beagas “rings” (894 and 3105) and frætwe “treasures” (896 and 3133). To emphasize the extent of their respective plunder, the dragon in the Sigemund episode is named hordes hyrde “guardian of the hoard” (887), and likewise the Beowulf-dragon is characterized repeatedly as hordweard “hoard-guardian” (2293, 2302, 2554, 2593), an epithet otherwise used throughout poem to describe kings, such as Hroðgar (1047) and Beowulf (1852).

Smaug’s hoard is equally impressive, and Tolkien describes the dragon atop his treasure: “Beneath him, under all his limbs and his coiled tail, and about him on all sides stretching away across the unseen floors, lay countless piles of precious things, gold wrought and unwrought, gems and jewels, and silver red-stained in the ruddy light” (215). Likewise when Smaug attacks, Bard of Lake-town acknowledges that the dragon is “the only king under the Mountain we have ever known” (248). Smaug similarly styles himself a king in his riddling conversation with Bilbo. Before he journeys to destroy Esgaroth, Smaug proudly remarks that “They shall see me and remember who is the real King under the Mountain!” (233).

Indeed, it is the hoarded wealth of a dying people that lures the Beowulf-dragon to the barrow (2270-72), and similarly, in Tolkien’s Hobbit, we learn that the dwarves’ obscene wealth is what lured Smaug to Erebor in the first place. Thorin explicitly notes how their hoard attracted Smaug:

“So my grandfather’s halls became full of armour and jewels and carvings and cups, and the toy market of Dale was the wonder of the North. Undoubtedly, that was what brought the dragon” (23).

Although the greedy wyrm “serpent” (891) that Sigemund kills is not described as particularly destructive, the avaricious Beowulf-dragon becomes belligerent once its wealth is disturbed by an anonymous thief, who steals its dryncfæt deore “precious drinking-cup” (2254). The narrator explains that after the wyrm (2287) is robbed of his prized chalice, he ravages the countryside causing widespread destruction.

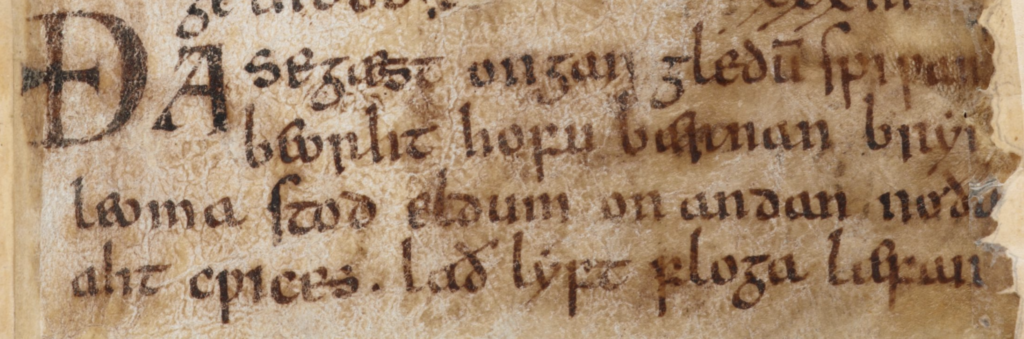

| Beowulf, 2312-27 |

| Ða se gæst ongan gledum spiwan, beorht hofu bærnan; bryneleoma stod eldum on andan. No ðær aht cwices lað lyftfloga læfan wolde. Wæs þæs wyrmes wig wide gesyne, nearofages nið nean ond feorran, hu se guðsceaða Geata leode hatode ond hynde; hord eft gesceat, dryhtsele dyrnne, ær dæges hwile. Hæfde landwara lige befangen, bæle ond bronde. Beorges getruwode, wiges ond wealles. Him seo wen geleah. Þa wæs Biowulfe broga gecyðed snude to soðe, þæt his sylfes ham, bolda selest, brynewylmum mealt, gifstol Geata. |

| “Then the spirit began to spew flames, burning the bright buildings. The burning-light [i.e. dragon] remained in anger toward all humans. The loathsome air-flier wanted to leave nothing alive there. The war of the serpent, the enmity of the narrow-hostile one, was widely seen, near and far—how the war-harmer hated and humiliated the Geatish people. It shot back to its hoard, its secret lordly-hall, a while before daybreak. The land-citizens had been surrounded by fire, by flame and brand. It trusted in its barrow, war and wall. The expectation for him was deceived. Then was the terror known to Beowulf, quickly to truth, that his own home, the best of houses, melted in burning-waves, the gift-throne of the Geats.” |

In Tolkien’s Hobbit, widespread devastation occurs when Smaug first plunders the wealth from the dwarves, unlike in Beowulf, where the hoarders are long-dead (2236-70). Pollution seems to accompany Smaug, and in Thorin’s retelling of the dwarves’ exile from Erebor, he describes how “A fog fell on Dale, and in the fog the dragon came on them” (23). Smaug again causes calamity when his hoard is disturbed, and Bilbo—like the Beowulf-thief—steals a treasured cup from the dragon. Bilbo accidentally directs Smaug’s attention toward Lake-town, and when the dragon attacks, he arrives with “shadows of dense black” (249) that engulfs the city.

Although both dragons lay waste to the surrounding region, Smaug’s pollution of Middle-Earth expands well beyond the scope of his medieval predecessor. Indeed, as a result of Smaug, the environment has been poisoned, and a once lush and thriving place had withered as a result of excessive smoke and heat.

I would argue that for Tolkien—whose environmentalism is no secret—Smaug represents a more contemporary form of dragonomics with special attention toward the ways in which greed drives war and industry, which pollutes the land and skies. The smog episodes in London throughout the 19th and 20th centuries–which culminated in the “Great Smog” of 1952 that killed 4,000 people–may not be part of the “philological jest“ of the dragon’s name (since Tolkien describes the etymology of Smaug as derived from the past tense smaug of the proto-Germanic smugan “to squeeze through a hole” in his 1938 Observer letter); nevertheless, Smaug becomes a representation of the dragonomics more closely associated with industrialization, which promised wealth but delivered also ecological catastrophe. Tolkien emphasizes that “his hot breath shriveled the grass” (219) and “The dragon had withered all the pleasant green” (229).

Smaug is characteristically avaricious, and Thorin describes him as “a most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm called Smaug” (23).” Tolkien refers to Smaug’s environmental impact as “The Desolation of the Dragon” (203, 255), and the author imagines an earlier, greener and more plentiful time before the dragon made his mark:

“There was little grass, and before long there was neither bush nor tree, and only broken and blackened stumps to speak of ones long vanished” (203).

I would argue that Smaug’s pollution changes the climate of Middle-Earth, affecting the land and the skies, but also the rivers and woods (such as the poisoned river and forests encountered in Mirkwood), and even the Elf-king’s woodland realm and the human merchant city of Lake-town. A conversation between Bilbo and Balin emphasizes Smaug’s lingering effect. Bilbo wagers that ‘The dragon is still alive—or I imagine so from the smoke’ (204), but Balin is worried about the lasting pollution of Smaug, and so the dwarf objects. Balin explains how Smaug “might be gone away some time … and still I expect smokes and steams would come out of the gates: all the halls within must be filled with his foul reek” (204). Bilbo discovers the truth of the dwarf’s words, for even when Smaug is not at home, “the worm-stench was heavy in the place, and the taste of vapour was on his tongue” (235).

I offer this interpretation of Tolkien’s dragon, because I would suggest that Smaug may be productively read as a representation of climate change, in the sense that the dragon is a force of smoke and heat which destroys ecosystems and disrupts the environment in much deeper and more long-lasting ways. Indeed, Tolkien reiterates the ecological cost of Smaug’s presence, and he describes how “his hot breath shriveled the grass” (219) and “The dragon had withered all the pleasant green” (229).

Since the president’s declaration of a national emergency with regard to the alleged immigration crisis on the southern border of the United States, many have already begun to discuss the potential for a future president to declare a national emergency in order to act on climate change more comprehensively, if necessary. We are already imagining our environmental crisis as the monster it threatens to be.

At the center of our modern struggles with dragonomics, I would argue, the problem of avarice endures. It is greed, especially from the fossil fuel lobby and the major energy companies (many linked to nations themselves), which have stalled and prevented developments in renewable energies in order to reduce our carbon footprint. And greed continues to obstruct human efforts to act upon the issue, both globally and as individual nations, as the looming dragon grows ever bigger and more ominous.

Dragonomics is not simply about making money, it is about plundering it and more importantly hoarding it. I have already referenced how greed motivates Smaug’s plunder, and I will turn now to Tolkien’s description of dragon-hoarding:

“Dragons steal gold and jewels…and they guard their plunder as long as they live….and never enjoy a brass ring of it. Indeed they hardly know a good bit of work from a bad, though they usually have a good notion of the market value” (23).

The socially detrimental result of hoarding obscene wealth marks the very pinnacle of greed in the Hobbit, which Tolkien describes specifically as “dragon-sickness” (305). I would argue that hoarding is also a major motivating force when it comes to our environmental crisis, especially with regard to our delayed and incoherent responses to the issues climate change presents. This is especially true with regard to the oil companies and related special interests linked to fossil fuels, which in their attempts to consolidate and retain their wealth and virtual monopoly on energy, have awoken a terrible dragon, one that will dwarf Smaug and will require heroism—not only from those in leadership positions, but also from the people. Indeed, when it comes to the crisis of global pollution and climate change, Bilbo’s sentiments ring truer to me than ever: “‘This whole place still stinks of dragon….and it makes me sick’” (267).

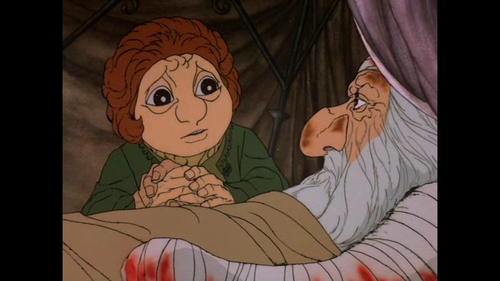

Still, it is Thorin’s famous deathbed realization that speaks most directly to today’s crisis, if the goal is to work together globally in order to combat our collective environmental crisis. The moment calls for a collective change of attitude, particularly from those who maintain that profits and economics necessarily trump ecological concerns. As even the miserly dwarf-king, formerly seduced by “the bewitchment of the hoard” (240), must admit at the end of his life: “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world” (290).

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate in English

University of Notre Dame

Editions and Translations:

Tolkien, J. R. R. 1937. The Hobbit, or, There and back again. George Allen & Unwin.

Pages correspond to:

Tolkien, J. R. R. 1937. The Hobbit, or, There and back again (Mass Market Edition). HarperCollins Publishers. 2012.

Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation (Bilingual Edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2000.

Klaeber’s Beowulf (Fourth Edition), ed. R.D. Fulk, Robert E. Bjork, John D. Niles. University of Toronto Press. 2008.

Further Reading:

Abram, Christopher. Evergreen Ash: Ecology and Catastrophe in Old Norse Myth and Literature. University of Virginia Press. 2019.

Cooke, William. “Who Cursed Whom, and When? The Cursing of the Hoard and Beowulf’s Fate.” Medium Aevum 76.2 (2007): 207-224.

Evans, Jonathan D. “A Semiotics and Traditional Lore: The Medieval Dragon Tradition.” Journal of Folklore Research 22 (1985): 85-112.

—. “‘As Rare as They Are Dire’: Old Norse Dragons, Beowulf and the Deutsche Mythologie”: 207-269. In The Shadow-Walkers: Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous, ed. Tom Shippey. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 2005.

Lawrence, William Witherle. “The Dragon and His Lair in Beowulf.” PMLA 33.4 (1918): 547-583.

Lee, Alvin A. Gold-hall and Earth-dragon: Beowulf as Metaphor. University of Toronto Press. 1998.

Lionarons, Joyce Tally. The Medieval Dragon: The Nature of the Beast in Germanic Literature. Hisarlik Press. 1998.

Rauer, Christine. Beowulf and the Dragon: Parallels and Analogues. Boydell and Brewer. 2000.

Shippey, T.A. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology. Mariner Books. 2003.

Silber, Patricia. “Gold and Its Significance in Beowulf.” Annuale Mediaevale 18 (1977): 5-19.

Wonderful! As good a scholarly paper as I have ever read. I will certainly leave my email. I’m eager to read everything! What a treasure.

Sharon

This also makes me think of the “Scouring of the Shire,” and Saruman. Instead of greed for riches and treasure its more a greed of power. Have you ever thought of tying that in to this?

Ben, thanks for your generous comment and bringing to my attention a potentially related moment in the “Return of the King” that I hadn’t considered and do not discuss. Indeed, it does seem to me that perhaps power is the major motivator in the “Scouring of the Shire” chapter. The Shire surely has transformed in this chapter (from what we see early in “The Fellowship of the Ring”), though in my mind it resembles more of a totalitarian state than an environmental wasteland (like the “Desolation of the Dragon” from the Hobbit). I guess, I would therefore connect the scouring more directly with the war of the Ring (as you say, related to desire for power). Perhaps an artificial distinction on my part, and certainly I agree that the power-play by Saruman in the Shire results in its own form of social (and environmental) devastation.

And, oh how the greedy and power-hungry transform and trouble our own world! Thanks again for reading.