Gerard David’s painting The Judgment of Cambyses was placed in the town hall of Bruges at the end of the fifteenth century. This diptych graphically depicts a gruesome tale from Herodotus in which King Cambyses II ordered a corrupt judge named Sisamnes to be flayed alive and the detached skin draped over his chair, as seen in the background of right panel. The image and its placement were part of the tradition of exempla iustitiae, providing moral lessons (or warnings) to urban administrators through images from legend and history.[1] As a late medieval alderman, one should strive for impartiality so that one does not end up in Sisamnes’s position!

To my knowledge, no corrupt judges were even flayed alive in Bruges. Nor did the judges themselves ever sentence anyone to be flayed. However, rituals of bodily punishment could still involve visual spectacle. In 1488, around the time the town commissioned this painting and in the midst of a revolt against the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (himself briefly imprisoned in the city), Bruges executed several high-ranking officials who had been loyal to Maximilian. Some suggest that the likeness of one such official, Pieter Lanchals, appears in this painting as Sisamnes.[2] Although the real Pieter Lanchals was not flayed, his decapitated head was displayed on the city gates.[3]

A rebellious city displaying the decapitated head of a detested politician fits well into popular stereotypes about the brutality of medieval justice. But was this representative of everyday judicial practice in Bruges and other Flemish cities in the fifteenth century? My research project is interested not in the infamous executions of political figures, or the iconography of imagined justice, but instead, ordinary judicial procedures and quotidian violence.

Late medieval cities in Flanders did practice capital punishment, but relatively few criminal cases ended at the gallows. Instead of bodily punishments, the urban aldermen who served as judges sentenced many of those who most passed through their courts to fines, temporary banishments, or penitential pilgrimages.[4] Medieval justice was characterized by multiple routes of resolution and not all disputes ended in this type of formal sentence. Many cities had designated legal officials who helped disputing parties negotiate peace agreements, both temporary and perpetual. In the Low Countries, formal reconciliations (called verzoening) culminated in a ceremony where both sides swore friendship, resolving enmity even after a feud had escalated to homicide.[5]

Additionally, many cases did not end up before an urban court because a composition payment halted the prosecution.[6] A composition payment was a type of financial settlement that bailiffs accepted from a suspect on behalf of the state in exchange for not bringing formal charges against them. The amount of this payment varied because it depended on a negotiation between the bailiff and the suspect. Composition could resolve a wide variety of offenses, including those eligible for capital punishment. Homicide cases, in fact, appear in records of bailiff composition far more often than they do in records of execution.[7]

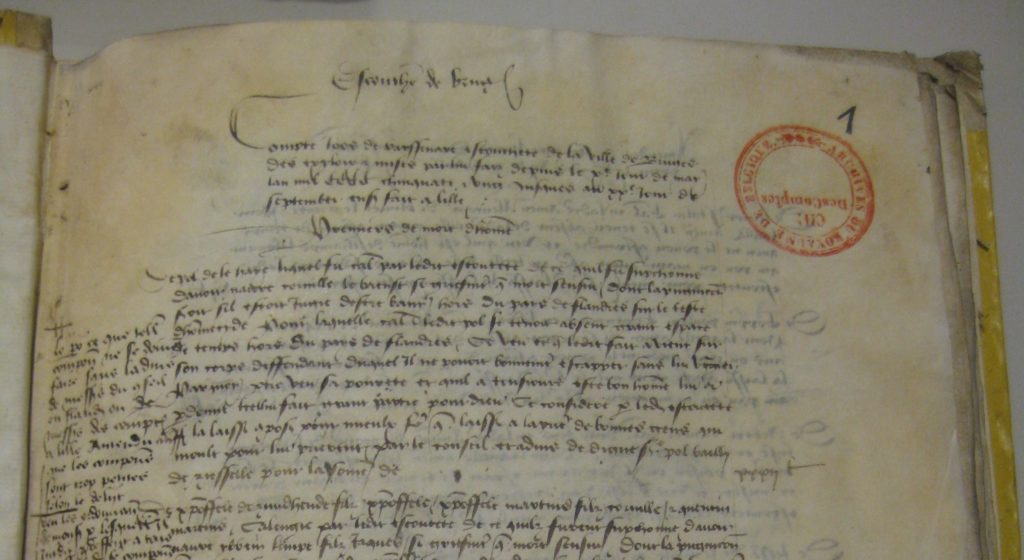

A successful composition payment for homicide depended on several factors: the good reputation of the accused, the context of the killing (self-defense or revenge), the bad behavior of the victim (he started it), and, most importantly, that peace had been made with the family of the victim. In 1451 in Bruges, the bailiff (called the schout in Bruges) accepted a composition payment of 32 livres from Pol de le Haye because “he was suspected of having injured Cornille le Baenst so grievously that death ensued”. The record notes that if convicted the punishment would have been banishment on pain of death. However, an agreement to pay a composition payment was reached because the event “happened in defense of his body from which he could not easily escape without avenging himself” and the opposing party forgave him “in view of his poverty and because he had always been a good man.”[8]

At the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth centuries, these patterns were changing, and composition payments and peace agreements gradually lost their importance in Flemish urban justice.[9] The more “medieval” practices that emphasized negotiation and peacemaking were gradually edged out by formal judicial procedures more oriented towards punishment than reconciliation. My book project, The Invention of Homicide, examines this transition and shows how changing cultural perceptions of honor, killing, and the common good contributed to the rise of early modern punitive justice. Though the flaying of Sisamnes was allegorical and not representative, the painting was created in a time when judicial spectacle was beginning to play a larger role in everyday legal practice.

Mireille J. Pardon, Ph.D.

Mellon Junior Faculty Fellow

Medieval Institute

[1] Hugo van der Velden, “Cambyses for Example: The Origins and Function of an exemplum iustitiae in Netherlandish Art of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” Simiolus 23, no. 1 (1995): 5-62.

[2] Helene E. Roberts, ed. Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art (New York: Routledge, 1998), 457.

[3] Marc Boone, “La justice en spectacle. La justice urbaine en Flandre et la crise du pouvoir « bourguignon » (1477-1488),” Revue historique 625, no. 1 (2003): 59-62.

[4] Ellen E. Kittell, “Travelling for Atonement: Civilly Imposed Pilgrimages in Medieval Flanders,” Canadian Journal for Netherlandic Studies 31, no. 2 (2010): 21-37; Marc Boone, “Mécanismes de contrôle social: pèlerinages expiatoires et bannissements,” in Le prince et le peuple : Images de la société du temps des ducs de Bourgogne 1384-1530, ed. Walter Prevenier (Amsterdam: Fonds Mercator, 1998), 287-293.

[5] Hans de Waardt, “Feud and Atonement in Holland and Zeeland: From Private Vengeance to Reconciliation under State Supervision,” in Private Domain, Public Inquiry: Families and Life-styles in the Netherlands and Europe, 1550 to Present, ed. Anton Schuurman and Pieter Spierenburg (Hilversum: Verloren, 1996), 15-38.

[6] Guy Dupont, “Le temps des compositions. Pratiques judiciaires à Bruges et à Gand du XIVe au XVIe siècle (Partie I),” in Préférant miséricorde à rigueur de justice: Pratiques de la grâce (XIIIe-XVIIe siècles), ed. Bernard Dauven and Xavier Rousseaux (Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2012), 53-95.

[7] Mireille Pardon, “Necessary Killing: Crime, Honour, and Masculinity in Late Medieval Bruges and Ghent,” in Patriarchy, Honour, and Violence:Masculinities in Premodern Europe, ed. Jacqueline Murray (Toronto: Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, 2022), 71-91.

[8] Archives générales du Royaume, Chambres des comptes, 13776, f. 1r.

[9] Mireille Pardon, “Violence, The Nuclear Family, and Patterns of Prosecution in Late Medieval Flanders,” Medieval People 37, no. 1 (2022): 37-59.