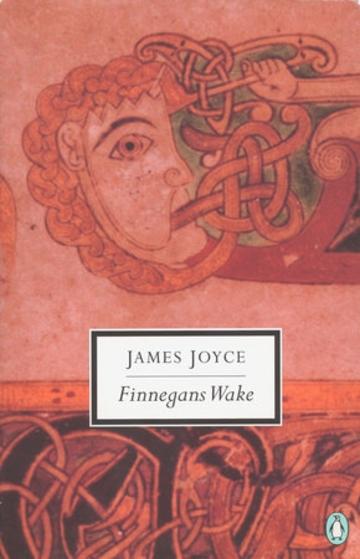

Umberto Eco famously described James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake as “a node where the Middle Ages and the avante-garde meet” (xi). For Eco, Joyce’s obsession with order and architectonics had a medieval character, and the Wake frequently refers to the Book of Kells as a kind of emblem of Irish modernism. A whole host of iconic medieval texts is put on display in the “museyroom” (8.09), or the museum that Joyce builds in order to warehouse all of human history. The surahs of the Koran echo in Joyce’s female protagonist, Anna Livia Plurabelle, who is described as “Annah the allmaziful” (104.01), and we move from here to the Annals of the Four Masters towards universal theories of history like Giambattista Vico’s Scienza Nuova.

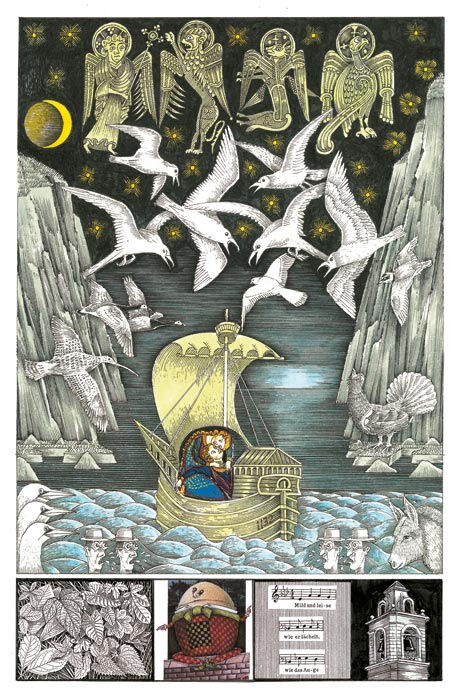

However, the extent of Joyce’s research into the Scandinavian influences on Irish and British culture has been underappreciated until somewhat recently. Thanks to the work of genetic scholars like Daniel Ferrer, and others involved with the Genetic Joyce Studies project, we now have a fuller picture of the depth of the Irish author’s appreciation of the history of Dano-Norwegian conquest. The Wake creates a speculative cartography, drawing on the ways in which the Scandinavian incursions into the western European peninsula—“the penisolate war” (FW 3.06)—impacted the cultural geography of Ireland. Ireland becomes a microcosmic composite of diverse global histories of migration in the Wake, and the historiographical adage that the Vikings became ‘more Irish than the Irish themselves’ plays out in Joyce’s mosaic of native-settler miscegenation: a process of “Noirse made Earsy” (314.27), or Norse made Irish/Erse.

The imaginative topography traced by the Wake ‘spatchcocks’ the totality of global history onto the local map of Dublin and its environs. As Joyce uses the course of the river Liffey to delimit the world-historical synecdoche that is Dublin, he draws on writers like the nineteenth century historian Charles Halliday. Halliday’s work, The Scandinavian Kingdom of Dublin, identified the Norwegian settlement of Dyfflinarsky with the inland route that the Liffey takes from Dublin Bay to the ‘Salmon Leap’ in Leixlip. This archaic territorial map has several notable features of Scandinavian origin, and even as early on as Joyce’s A Portrait, we see the influence of Halliday in references to the existence of a thingmote—a primitive structure that survives at the centre of Joyce’s imaginary Dublin as a vestigial icon of lost ages of Scandinavian sovereignty.

Indeed, the structure of the thingmote has profound symbolic significance in the Wake, as its hump-like shape resonates within the moniker of the Wake’s quasi-Nordic protagonist: Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (the ubiquitous HCE). An entire retinue of Scandinavian sovereigns populates the pages of Earwicker’s story, or his “Eyrawyggla saga” [48.16] (the comparison with the Icelandic Eyrbyggia Saga with Ireland was likely derived form A. Walsh’s 1922 history, Scandinavian Relations with Ireland during the Viking Period). The more familiar characters and incidents form the Poetic Edda crop up intermittently in Joyce’s novel (HCE assumes various forms of Odin’s name, and Yggdrasill and the hanged god theme lie behind the book’s recurrent theme of the scapegoat who is sacrificed). Indeed, from Thórodd, to Harald Bluetooth, to Sitric Silkenbeard—the Wake is heavily invested in bringing the expansionist networks of Norse hegemony into close proximity with more ‘Celtic’ accounts of the roots of Irish culture (indeed, the Tripartite Life of St. Patrick is a recurring nativist source, and the Wake returns frequently to St. “Peatrick” [3.10] as a satirical symbol of earthy, native identity).

While much of this historiographical overlaying of chronicles and pseudo-histories is designed to critique the ethno-purism of the Gaelic Revival’s celticization of history, it also speaks to the universal tendency of national cultures to ‘invent’ their own traditions—especially as this invention involves appropriating the histories of minority cultures. Norse references often displace the homely founder-narrative of Gaelic authenticity and rootedness in the Wake, and in Book Two, Chapter Three, for instance, HCE becomes a Norwegian sea-captain, who is naturalized as an Irish citizen through his marriage to Anna Livia. This episode recalls various incarnations of the invader/betrayer narrative that has defined Irish history, and the way in which he is domesticated and hybridized by the Celtic influence (becoming a “Scowegian” [16.06] and an “Eirewhigg” [175.17]), puts into question any assumptions about the uninterrupted purity of the Celtic lineage.

While Joyce introduces a Nordic element in order to desacralize Irish mono-culturalism, the Wake draws on a unique tendency within early twentieth-century historiography to complicate ethnic narratives by emphasizing the influence of peripheral, colonized cultures. Indeed, we can see how Joyce was actively searching for what could be called a counter-hegemonic chronicle of Norse-Irish history by looking at the complex array of notebooks and draft sheets for this chapter. These sources are often used by Joyce scholars to support their genetic claims about the gestation and composition of Finnegans Wake. As Ian MacArthur and Viviana Braslasu point out, in his notebooks of 1926 (V.B.17) and 1936 (VI.B.37), Joyce was reading and annotating a book by the Norwegian historian Alexander Bugge. Here we find references to the “Danelagh” (or Danelaw), to Magnus Barefoot, and to a variety of other tid-bits of Dano-Norwegian provenance. Bugge’s A Contribution to the History of the Norsemen in Ireland would have been attractive to Joyce—the counter-hegemonic writer, who wished to challenge monolithic histories. The Norwegian historian’s work contains chapter titles like “The Royal Race of Dublin”—a study of the elite Scandinavian inflections of medieval Irish culture. While this Nordicization of Irish history might appear to smack of Norwegian chauvinism, it is also deeply invested in complicating the Norwegian narrative of cultural purity, as a micro Irish note is introduced into the macro-schema of Viking supremacy (Bugge had also won a Nansen Foundation in 1903 award for an essay on “How or to which extend have the Norse, and particularly the Norwegians, culture, way of living and society been influenced from the Western Countries [ie. Ireland and the British Isles]”.

On the negative side, we can also see how the “becoming-minor” of national historiography could enable more domineering cultures to include minority cultures within their assimilationist narratives of national superiority. The politics of Nordic historiography in the early twentieth century was fertile ground for exploring the ways in which historical revisionism was used to articulate a clearer national identity in times of crisis (Norway and Sweden were in an identity crisis after the dissolution of their union in 1905). However, Joyce’s habit is to ridicule every nation’s proclivity to co-opt the history of minority political subjects. While Ireland becomes a positive source of talkback to national chauvinism in the Norwegian context—complexifying the tapestry of Viking history—Great Britain had been more resistant to Irish charges of cultural appropriation.

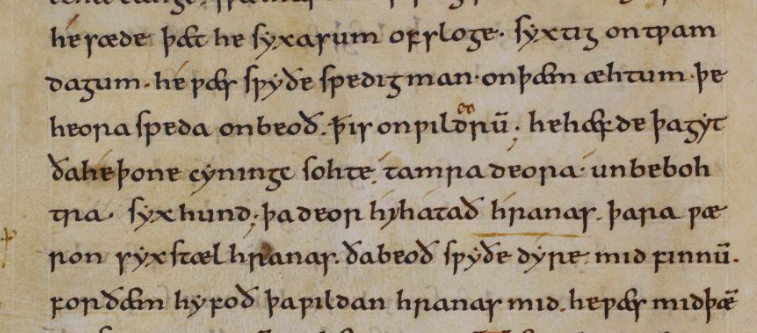

As British Anglo-Saxonists articulated their own version of national history throughout the nineteenth century, Ireland often features in their revisionist schema as a minority partner only. Attempts to archive an autonomous Gaelic literature had many pitfalls during the period of British colonization, as incidents like the Ossian controversy demonstrated. In this way, the ‘Celtic note’ (as critics like David Lloyd have made clear), was always expressed within a clear hierarchy of colonizer/colonized, modern/primitive—primary history versus secondary account; the authentic ‘Angle’ versus the imitative ‘Celt’. The self-fashioning of British identity (which accelerates during the Victorian era) was thus tied up with an emergent field of medieval scholarship. This field provided an intellectual justification for jingoism, and Anglo-Saxonists would play a key role in subordinating problematic minority cultures to a master narrative of national (namely, ‘Anglo-‘) culture.

The problem of Scandinavian identity upsets this kind of national chauvinism in the Wake. It functions in a multivalent fashion—less as a distinct culture, or a clear form of geopolitical identity, so much as a repertoire of possible colonial subject-positions. Joyce dramatizes the reversibility of dyads like colonizer/colonized and settler/native, and identity becomes a negotiable and heterogeneous phenomenon, as it is written and rewritten in the cyclical drama of conquests and colonisations in the Wake.

The Wake cultivates a pervasive aura of Norse-ness in-order-to articulate the impure nature of Irish identity—which was defined by successive waves of conquest and occupation (from the Vikings, to the Normans, to the modern British state). As we encounter the bellicose reparteé of two Neanderthal men—Mutt and Jute—in the first chapter of the novel, Joyce challenges us to develop an ethno-critical kind of thought. As Mutt encounters Jute, the hybrid native meets the ambiguous colonizer/Jutlander, and here Joyce plays with and inverts the roles of native and invader, moving beyond Manichaean constructions of history. In so-doing, Joyce radicalizes and repurposes the hackneyed trope of the Vikings’ assimilation to native Gaelic culture, and while the latter become “more Irish than the Irish themselves”, we are left with the sense that the Irish ‘mutts’ become less like themselves by virtue of the same process.

To further this deconstruction of historical roles, the Battle of Clontarf becomes a teachable moment in the Wake, as it works to complicate the received Manichaean narrative that the foreign invader was somehow expelled by the resilient natives in 1014. As Joyce himself remarks:

Finally, the bloody victory of the usurper Brian Boru over the nordic hordes on the sand dunes outside the walls of Dublin put an end to the Scandinavian raids. The Scandinavians, however, did not leave the country, but were gradually assimilated into the community, a fact that we must keep in mind if we want to understand the curious character of the modern Irishman (CW 159-60).

This is taken from a lecture that Joyce gave in Trieste on the topic of Irish identity in 1907, ironically entitled “Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages”. Here, the Wake’s vision of “miscegenations on miscegenations” (18.20) comes to the fore, as Ireland functions as what Thomas Hofheinz calls a “transparency”: a historiographical overlay of a diverse array of settler cultures. Joyce’s aim is to critique the homogenizing of identity that he saw at work in certain strands of Irish culture—from the church’s promulgation of a pan-Catholic, confessional culture, to what would seem like (from a modern vantage), rather chauvinistic references to a Gaelic “race” (we find this kind of language in Douglas Hyde’s The Necessity for De-Anglicizing Ireland, a talk given to the Irish National Literary Society, in 1892).

Rather than monumentalizing a supposedly stable monoculture, the Wake dwells on how history inevitably becomes a document of errors. We see an example of such “intermisunderstanding” (118.25), in the dialogue between Mutt and Jute in chapter One. The text that accompanies this bizarre piece of dialogue speaks of how the historian Tacitus has related a deceptive narrative of Hiberno-Germanic cultures: “as Taciturn pretells, our wrongstory shortener” (17.03). Here, the chronicle of history becomes a “taciturn” document—one that is unforthcoming; less of a clear and concise history, and more of a faulty chronicle, which is full of erroneous assumptions about foreign cultures. The inherent cultural relativism of a text like the Wake thus complexifies history, to the extent that it advances a hard historical relativism—challenging any attempt to devise a faithful account of the national past.

This lack of a definitive historical perspective is matched by the subversive interplay of Mutt and Jute, and they develop a sort of grudging complicity as they dialogue with each another (a sort of settler-colonial folie à deux, that upsets the rigid demarcation between settler and native). In their tenuous acts of civility towards one another, Mutt and Jute overturn any notion of a “pure” ethnic identity, as they come to represent the multifarious cultural exchanges that were involved in different phases of immigration and conquest. As they “swop hats and excheck a few strong verbs weak oach eather” (16.08), Mutt and Jute illuminate a history of linguistic cross-pollination, and the pair become a clownish, vaudeville duo, who deflate the grandiose pretensions of cultural chauvinisms that were becoming more prevalent during the composition of the Wake in the fascist 1930s. The latent violence of such exchanges is palpable, and Joyce effectively transplants the grander theatre of European tensions onto his own insular, Irish setting. The Wake constantly excavates and re-visits the histories of European violence. By domesticating and ironically reducing the gravity of this martial story of cultures (localizing it within in a remote enclave of the western European peninsula, like Ireland), he performs both a critique of epic jingoisms, and a de–sacrilization of the Hibernian insula sacra.

The specific mechanics of the interplay between Old Norse and Old English references that we find in Mutt and Jute will be detailed in our next blog. For now, it is worth noting how the political resonance of this cultural-linguistic patchwork begins to emerge. As Hofheinz has argued, Joyce’s engagement with historiography on Ireland’s Scandinavian roots is drawn from a scholarly tradition that was intimately bound up with both colonial antiquarianism, and the official outlets of English cultural production. Halliday, for example (whose Scandinavian Kingdom was clearly an influence on Joyce), was a historian commissioned by the Dublin Ballast Board—a municipal maritime body that had a quasi-governmental remit. As a member of the Royal Irish Academy in the mid-nineteenth century, Halliday joined the ranks of an academic organization whose history was inflected by a culture of colonial curatorship. The Academy was disproportionately patronized by the educated, Protestant elites of Ireland (one thinks of the Anglo-Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth and the statesman, Edmund Burke as notable members—critics of colonialism and slavery who could also be extremely paternalist in their attitude). It is thus impossible to separate the source-texts of Joyce’s Scandinavian fascination from the long history of official chronicles, and what was oftentimes an intense competition (between Irish and more ‘Anglo’-oriented intellectuals) for cultural legitimacy. The bellicose nature of historiographical debate—a veritable patchwork of cultural appropriations and revisionisms—is consequently encoded in the confrontational patois of Mutt and Jute. Here, also, Joyce uses the comic strip template of Mutt and Jeff to conjure a comic duo of primitive cavemen who are trying to muster the most rudimentary form of language competency. As they are excavated from some palaeolithic era like the Heidelberg Man (“our old Heidenburgh” [18.23]), these original hominids represent the historical extremes that founder-narratives of cultural legitimation will go to, and in the end they become little more than bungling diplomatic negotiators, engrossed in an awkward telephone conversation. Stay tuned for more on the archaeology and language archaism of this anti-colonial satire in our next blog post on the subject!

John Conlan, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

Selected Bibliography:

Braslasu, Viviana-Mirela and Ian MacArthur. “Norsemen in Ireland in Spree, Notebook VI.B.37”. Genetic Joyce Studies: 20.1 (2020).

Eco, Umberto. The Middle Ages of James Joyce: The Aesthetics of Chaosmos. MA: Harvard UP (1989).

Hofheinz, Thomas. Joyce and the Invention of Irish History: Finnegans Wake in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge UP (1995).

Joyce, James. The Critical Writings of James Joyce. NY: Cornell UP (1989).

Finnegans Wake. London: Penguin (1999). Lloyd, David. Nationalism and Minor Literature: James Clarence Mangan and the emergence of Irish Cultural Nationalism. CA: University of California Press (1987).