On this day three years ago, my first contribution to the Medieval Studies Research Blog, in which I connected the Wife of Bath’s Tale with contemporary rape culture, was published. In December 2017, the #MeToo movement was gaining momentum, and the survivors of sexual violence were thrust into the media spotlight. But while the public eye was focused on the victims who came forward in record numbers, Brock Turner, the former Stanford University student who was caught raping an unconscious 22-year-old woman in 2015, was attempting to have his multiple felony sexual assault convictions overturned. With “The Silence Breakers” taking center stage, we barely noticed when Turner was trying to sneak out the back door.

Witnessing how our collective gaze fixated on victims, I felt that the Wife of Bath’s Tale had something valuable to teach us about shifting our attention to the perpetrators of sexual violence and social reformation. I still do. So today, I return to the tale to consider how we can actively create a culture of consent. Rather than concentrating on violence, I want to highlight how the tale emphasizes education as a critical component of cultural reformation. After all, it is through education that the rapist knight is reformed in the tale.

As a refresher for those who have not recently read the Wife of Bath’s Tale or who may not be familiar with the Middle English poem from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the narrative begins with the protagonist knight’s rape of a maiden whom he meets in the woods. Called to the court of Camelot for his crimes, the knight escapes King Arthur’s condemnation to death only because the queen suggests an alternative: the knight will return to the court in a year and one day to provide an answer to the question, “What thyng is it that wommen moost desiren”?[i]

The task that the queen requires of the knight, in turn, requires that he receive an education – one through which he acquires information but also learns effective communication. In contrast to the knight’s singular concern with what he wants and the brutal assertion of his will over a young woman’s body, the endeavor upon which the knight embarks depends upon asking women what they want and listening to what they have to say. Over the course of the tale, the knight’s quest forces him to see that the answer to such a question is subjective. He discovers that women desire different things and, effectively, that women have wills of their own. His journey leads him to the only acceptable answer: above all things, women desire sovereignty. Returning to Arthur’s court, the knight acknowledges that women want autonomy. But his answer alone – the act of speaking the words aloud – does not suffice. Only after the knight puts his new knowledge into practice, specifically in a sexual context that compels communication with and respect for the woman in his bed, does he appear fully exonerated in the tale. In the end, the knight preserves his life and gains a wife with whom he lives happily ever after.

At this point, the fact that Chaucer may have committed rape himself deserves disclosure, since I’m striving to convey how a narrative penned by his hand that rewards a rapist can teach us about consent. But the Wife’s tale is fiction and the wife herself a fictional character; neither entity represents Chaucer the person nor reflects on his charges of raptus in 1380. It is paramount to understand that my interpretation of the tale and its teachings derive directly from the Wife’s wisdom as represented in her prologue and her tale. We should recall that the Wife is a survivor of sexual assault, and as I suggested three years back, if she has something valuable to teach us about combatting sexual violence, we must listen. According to Alisoun of Bath, education is the key to consent.

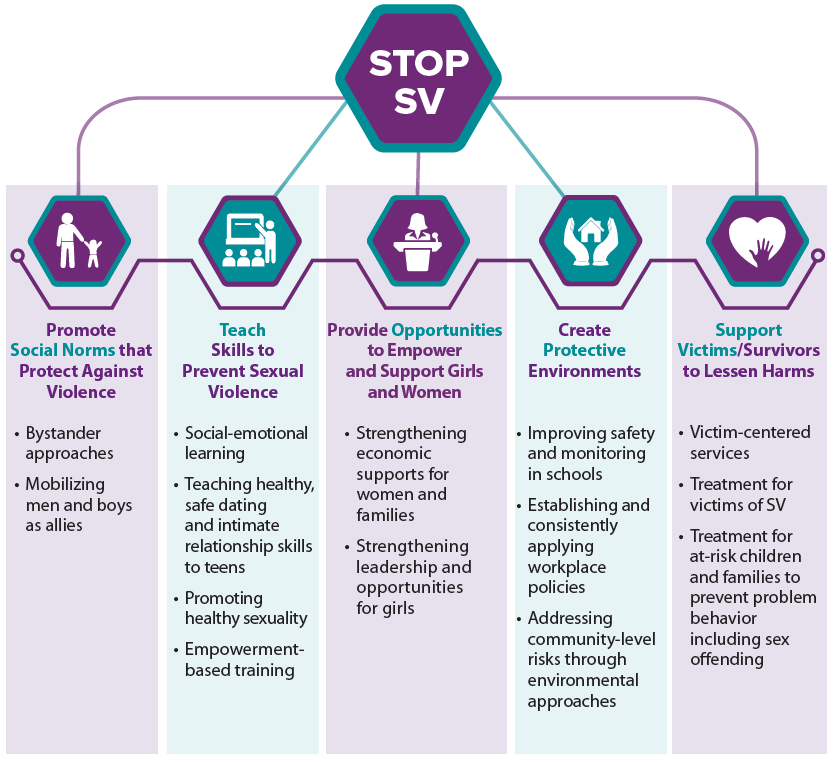

Without sexual education, we replicate the conditions in which rape culture thrives. Socially, we continue to idolize hegemonic masculinity, a paradigm that rewards attributes like virility, aggression, and dominance and, by extension, conflates sex with conquest, a combination that inherently undermines consent. At the same time, we generally shy away from conversations about what women want because sexuality, especially when it pertains to women’s pleasure, remains so stigmatized. The sexual education young people currently receive in the U.S. is inconsistent across the country and largely deficient in its emphases and omissions. On the one hand, public school curriculums traditionally highlight the dangers of sexual activity, attempting to frighten adolescents with pictures of disease and stories of unintended pregnancy. On the other hand, conservative states and institutions tend to employ an abstinence-only strategy, via which they articulate a particular set of values related to sexual behavior but do not necessarily provide information about sex. By instilling young people with fear and denying them information, these approaches to sexual education are antithetical to sexual health. Moreover, the absence of sexual education models silence where sexual activity is concerned. Consent, however, depends upon successful communication.

Comprehensive sexual education provides young people information about human bodies and sexual behavior that is pertinent to their everyday lives.[ii] It is crucial not only for their personal health but also for the health of others, particularly their romantic partners both present and future. Healthy relationships cannot happen without communication, and without engaging in intentional conversations about sex, students are prevented from practicing a skill essential to personal and communal sexual well-being.

Due to the deficits and overall incongruity of sexual education across the country, many young people enter their college campuses and their adult lives without the tools that enable them to make informed decisions and communicate effectively in sexual situations. During their first year of college, students should have access to a course on human sexuality that provides a comprehensive introduction previously unavailable to them and appropriate for them as adults. But not all colleges include sexuality studies in their course offerings. My own institution, for example, does not currently offer a course on human sexuality for its undergraduate population. Yet if students are not equipped with the information and skills necessary for fostering sexual health, it impairs our ability to develop a community in which consent becomes accepted as doctrine.

Comprehensive sexual education provides young people the information integral to navigating an omnipresent part of human experience, an aspect that affects us individually, as well as interpersonally. Conducting conversations about sex in an educational environment also establishes a visible and tangible connection between open communication and healthy sexuality. Communication, of course, cannot be separated from consent.

I want to be very clear: comprehensive sexual education need not eschew faith-based values, just as science need not exist apart from religion. Students can be taught the science surrounding sex alongside lessons about spiritual life. As Pope John Paul II said, “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world in which both can flourish.”

We all deserve to flourish. By foregrounding education, the Wife of Bath’s Tale begins to show us how.

Emily McLemore

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of English

University of Notre Dame

[i] Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry D. Benson, Houghton, 1987, pp. 116-22, line 905.

[ii] Bedbible Research Center. “Sex Education Statistics – The state of sexual education (+Dataset),” 2015, https://bedbible.com/sex-education-statistics/.