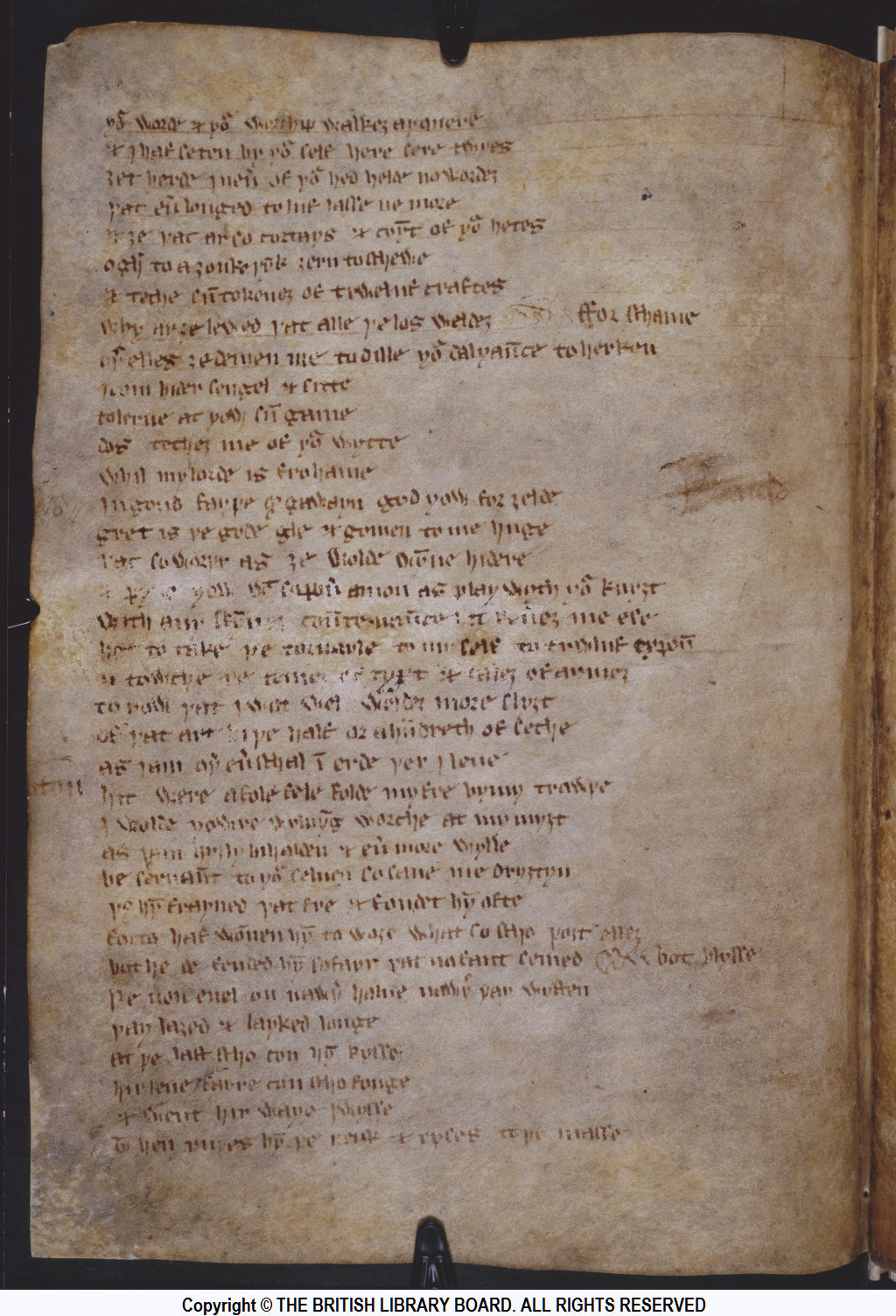

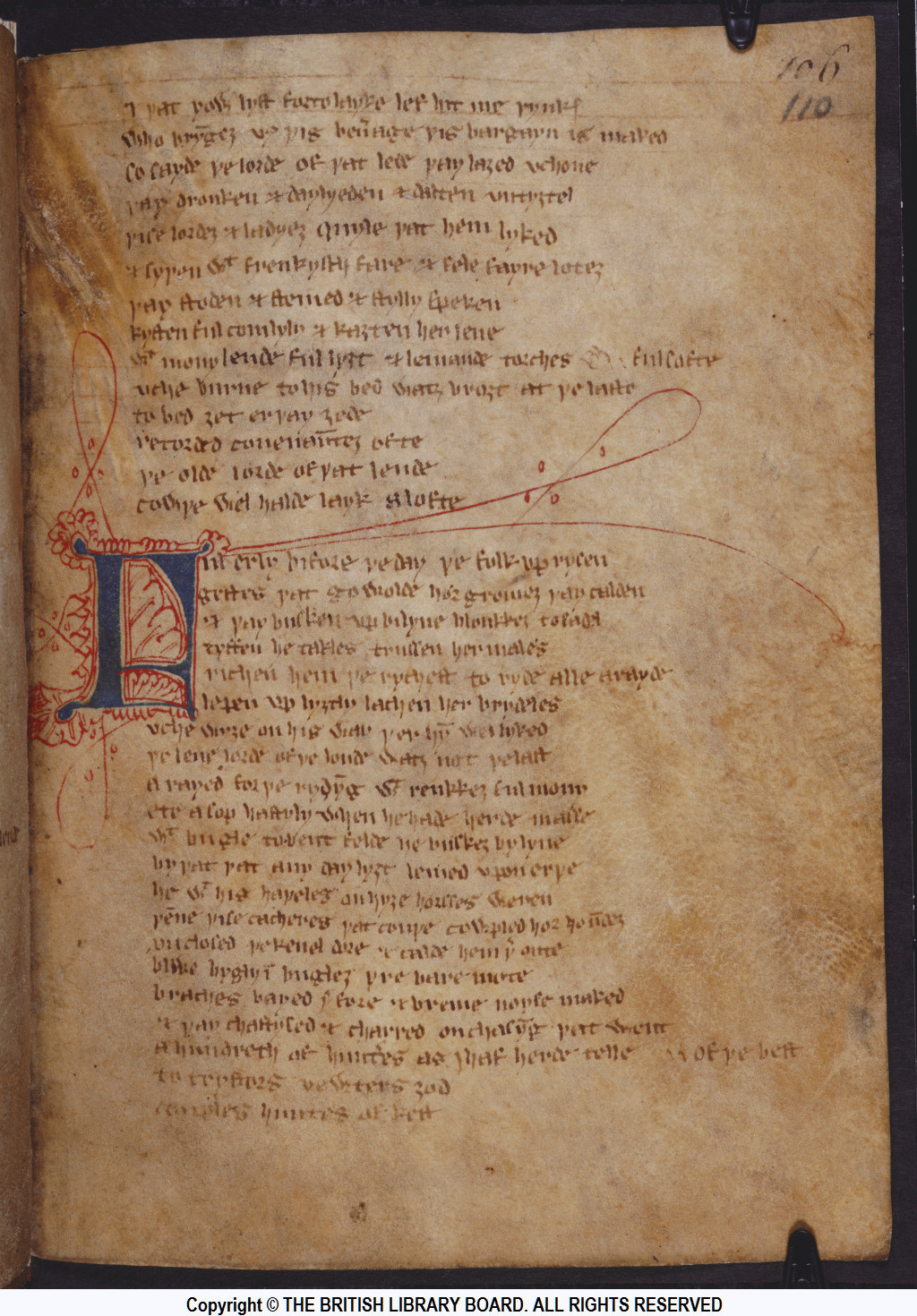

London, British Library, Cotton MS Nero A.x (pet-named the Gawain-Manuscript and at times the Pearl-manuscript) contains the only extant copies of some of the most celebrated Middle English literature. As a 14th century Middle English manuscript, and one that survives without any Anglo-Norman or Latin companion pieces, the illuminated initials and the various illustrations, mark it as a unique, multimedia project.

This can be taken a step further, as the audience of this manuscript would be twofold, namely those reading and experiencing the literature visually, and those listening and experiencing it aurally.

One of the most peculiar features of the manuscript may be the placement of the metrical “bob” in the last poem in the manuscript, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The respective bobs most often appear as many as two or three lines above its accompanying “wheel” directly before which, editors (and indeed most scholars) assume the bob would have been read. Despite that all editors from J. R. R. Tolkien onward move the bob in order to metrically perfect the poem, sloppiness on the part of the scribe seems doubtful considering the care taken in illuminating initials, thus the placements of these bobs may well be intentional.

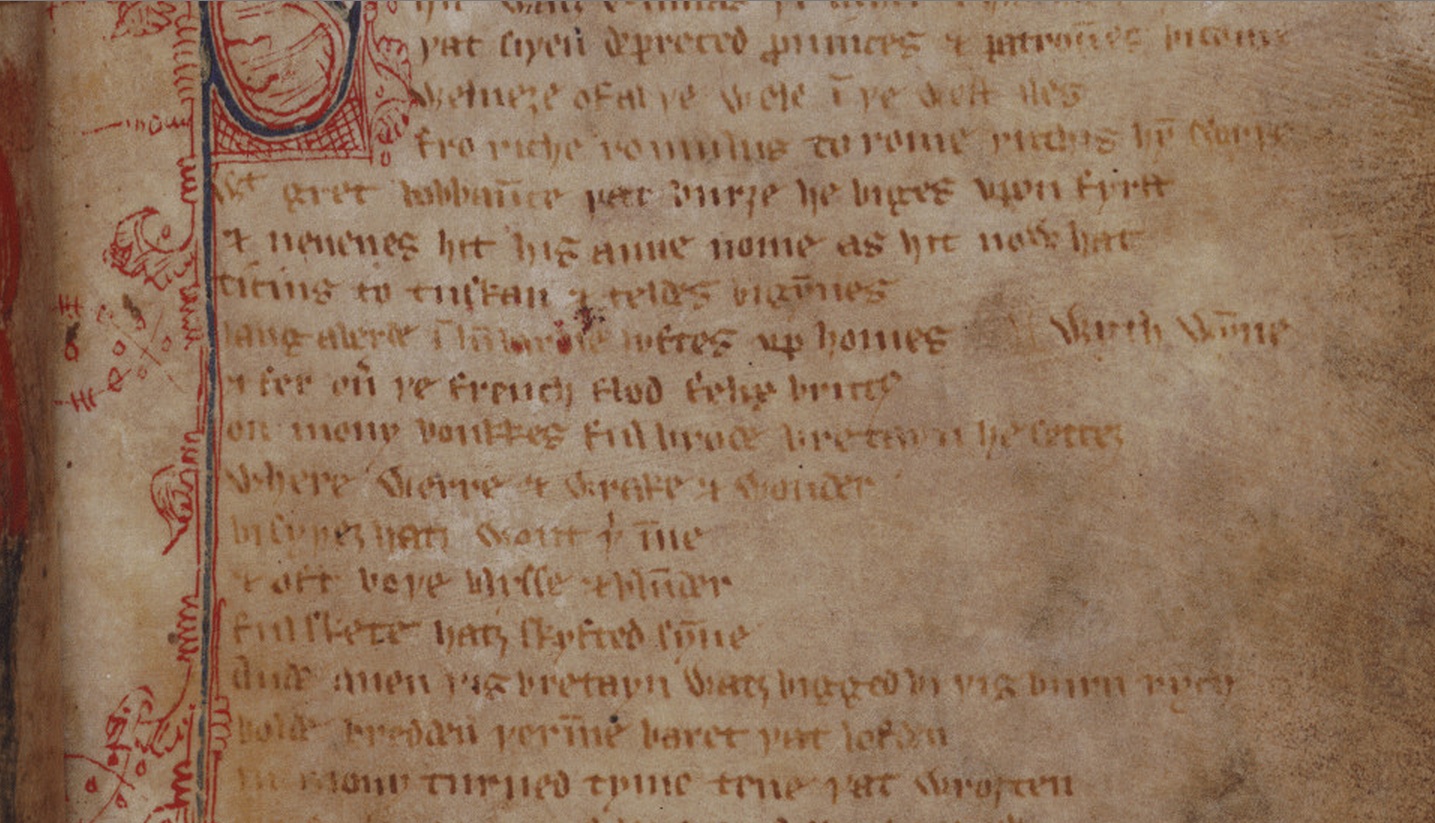

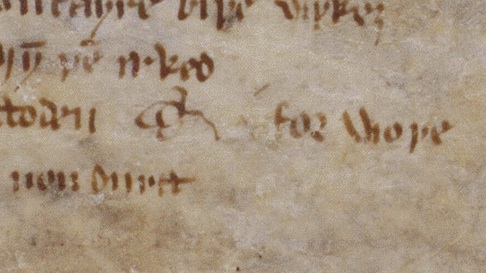

By positioning the bob in such a way, Kathryn Kerby-Fulton sees potential for equivocation and the possibility that this bob might be a floating marginal device resonating with more than one line. Because of the syntactic flexibility of a bob, it can in fact (sometimes much more sensibly) be understood in the context of where it actually occurs in the manuscript. For a reader of this text (which is to say a literate, visual audience), such an interpretation is appealing. Kerby-Fulton persuasively argues that wyth wynne, placed between lines describing the respective foundings of Rome and Britain, could equally apply to both joyful events.

Howell D. Chickering has an interpretation of the irregular positioning of the bob, which reflects aural reception and considers the performative function of the poem. The audience of such a performance would likely understand the bob in only one place, where it is spoken; however, Chickering argues that the bob often appears preemptively to alert the recitator of the abrupt shift in meter, and almost always is found on the same page as its accompanying wheel. In giving the recitator this warning, Chickering suggests the performance might move more smoothly. These two interpretations both highlight the importance of manuscript context in understanding both the literary texts and their multimodal means of understanding and experiencing the poem.

The manuscript also reveals that a symbol, called a “trefoil”, often accompanies bobs, and if this symbol serves to add emphasis, as Peter J. Lucas has demonstrated it does in the work of John Capgrave, the trefoils in Sir Gawain may similarly indicate the importance and purposeful placement of bobs. While the manuscript’s systematic reasons for employing certain symbols remains a mystery, it seems likely that there was some premeditated method to the scribal adornment of bobs with trefoils.

Indeed, analysis of the positioning of bobs in Sir Gawain demonstrates how close attention to the manuscript presentation of a text contributes to a better understanding of how it might have been read and performed.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of our ongoing series on Medieval and Early Modern Poetics: Theory and Practice.

Further Reading:

Baugh, Albert C. “Improvisation in the Middle English Romance.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 103.3 (1959): 418-454.

Borroff, Marie. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Stylistic and Metrical Study. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1962.

Chickering, Howell. “Stanzaic Closure and Linkage in “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” The Chaucer Review 32.1 (1997): 1-31.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts: Literary & Visual Approaches. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Lucas, Peter. “John Capgrave: Scribe and Publisher.” Transactions of the British Bibliographical Society V (1969).

Pearsall, Derek. “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: An Essay in Enigma.” The Chaucer Review 46.1-2 (2011): 248-260.

Putter, Ad. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and French Arthurian Romance. Oxford, England: Clarendon University Press, 1995.

Tolkien, J. R. R. and Gordon E. V. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, 2nd edition. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.