Although inventing a language might seem like a purely modern phenomenon, nearly a thousand years ago, the Benedictine Abbess, lecturer, composer, and visionary, Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) created her own language, the Lingua Ignota.

The Lingua Ignota can be found about halfway through the Riesen Codex (Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, Hs. 2, ff 461v-464v), also called the Giant or Chain Codex, a compilation of Hildegard’s theological writings that were collected near Hildegard’s death. The Lingua Ignota can also be found in the manuscript formerly known as the Codex Cheltenhamensis (Berlin, MS Lat. Quart. 674, ff. 57r-62r) (Higley, 145).

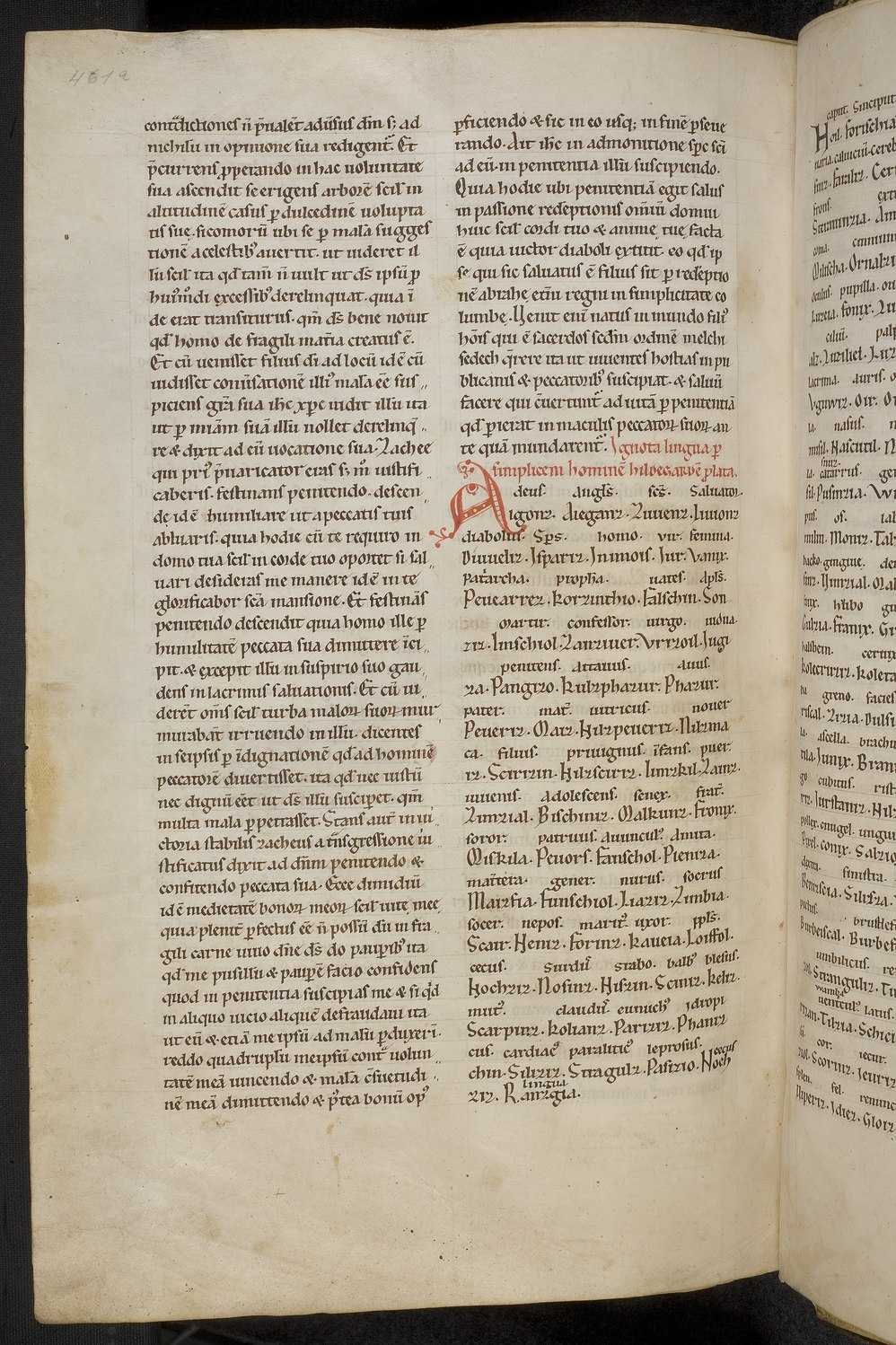

Apart from a sentence long introduction, the Lingua consists of a glossary of around 1000 words arranged hierarchically. Hildegard begins with the words for God and the angels, then proceeds to human beings, other animals, plants, and so on.

A sample of some of Hildegard’s words:

- Aigonz – God

- Aieganz – Angel

- Inimois – Human

- Korzinthio – Prophet

- Peueriz – Father

- Maiz – Mother

- Sciniz – Stammerer

- Kaueia – Wife

- Ornalz – The hair of a woman

- Milischa – the hair of a man

- Pusinzia – Snot

- Zizia – Mustache

- Fluanz – Urine

- Fuscal – Foot

- Sancciuia – Crypt

- Abiza – House

- Amozia – Eucharist

- Pereziliuz – Emperor

- Bizioliz – Drunkard

- Haischa – Turtle Dove

There are elements of German (particularly the use of the “z”) and Latin in Hildegard’s vocabulary. There is also German influence in her use of compound words. For example, her word for grandfather is Phazur which is the root of Kulzphazur, ancestor. Likewise most of her words for trees end in –buz, probably “bush”. Sarah Higley also identifies grammatical gender in Hildegard’s words, which roughly corresponds to the gender of those same words in either Latin or German (Higley, 103-4). Finally, her words are intended to be euphonic. When applicable, for example, the final two syallbles of her words form a trochee. This gives her language a bouncy, sing-song feel.

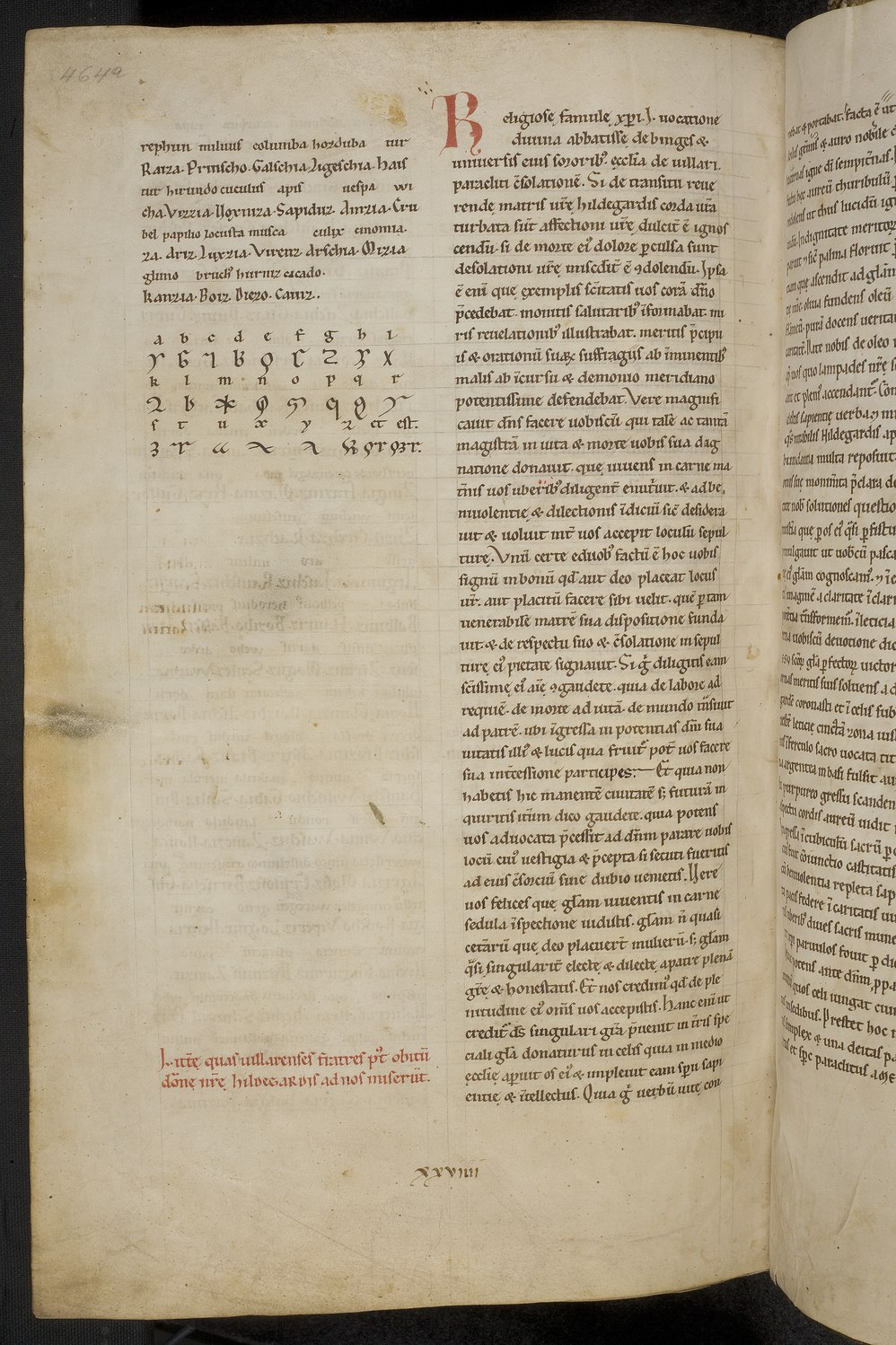

Along with her own language, Hildegard created an alphabet.

The alphabet shows some possible influence from Greek (or even Cyrillic) in the letter-forms for B, C, and M. The letter-forms for R ,U, X & Y have some resemblance to Roman Cursive. These letters also have some resemblance to the symbols of the zodiac.

So, why did Hildegard create this language? Although she never explicitly said why, it should not be understood outside of her theology, based in part on the limits of language. As Wittgenstein once said, “The limits of my language define the limits of my world”. If our language is limited, it will hinder our experience and appreciation of the divine. Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota thus may be an attempt to redeem our fallen language so that in the world it shapes, the natural holiness of all things (even urine and drunkards) will be manifest.

Works Consulted

Bingen, Hildegard von. Scivias. Trans. Columba Hart and Jane Bishop. New York: Paulist, 1990.

Higley, Sarah Lynn. Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

11 Replies to “Letter? I ‘ardly know ‘er: The unknown language (and letters) of Hildegard von Bingen”

Comments are closed.