The study of medieval poetics and literature has begun to benefit immensely from the boom in manuscript studies. We’ve seen, even in past entries on this blog, how the layout of a poem in a manuscript can affect the way it is read. It is worth considering as well how the layout of a manuscript page can affect the way we interpret a text even before we begin reading it. In the same way directors signal and elicit particular responses from viewers of film or theatre with mise-en-scène, a scribe attuned to the potential of mise-en-page (also ordinatio) employs different page layouts to ask readers to begin understanding a text in a generic fashion a priori to any close engagement with the text.

A sterling example of the power of mise-en-page is London MS Harley 2253, which offers a smorgasbord of literary treasures from medieval England matched by few manuscripts. A number of scholars have observed how certain choices related to layout point to ways of reading the manuscript. Kerby-Fulton, for instance, observes the speech-markers in Gilote et Johanne, making a text “ready for performance” (54). The mise-en-page in the Harley MS serves as a visual entrée for many of these texts (after all, we are often told that we eat first with our eyes, not our stomachs), asking a reader to consider how they will read before they begin to do so. Because its contents are varied, the manuscript gives us the chance to see how one scribe employed mise-en-page with different types of texts. Of these various genres, languages, and layouts in that manuscript, one text, King Horn, stands as an anomaly of both genre and layout that can go some way in suggesting how layout can influence our reading of a text.

This is not to suggest that the Harley scribe was absolutely consistent, but he was consistent enough to show that his choices in layout were not dictated by whim. For instance, the vast majority of texts with a rhyme scheme of abab or abababcc (with a bob) were written out in a long-line form, with two verses to a line. Poems with an aabb scheme were, with the sole exception of King Horn, written in short lines, usually in two or three columns to a page.

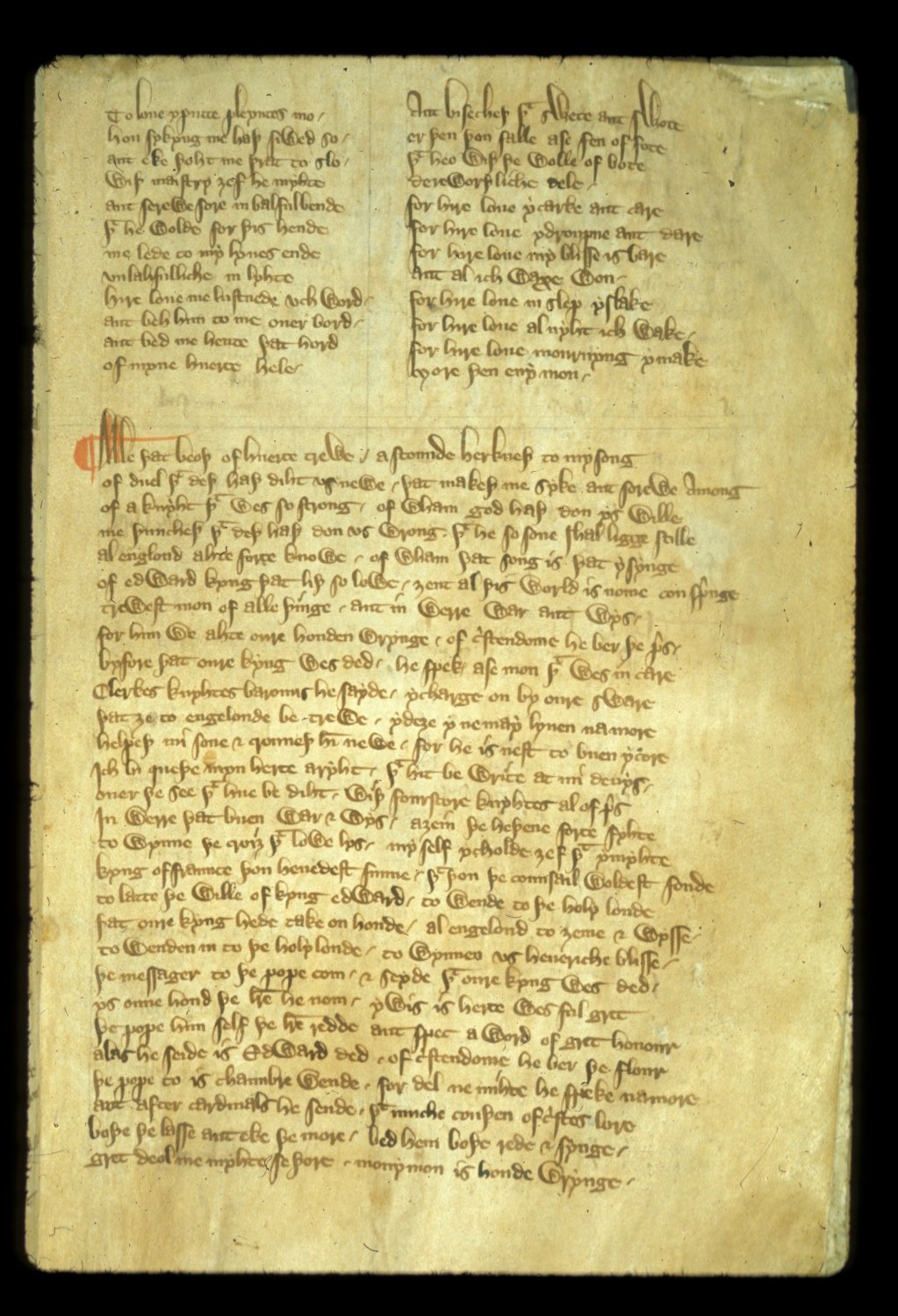

BL Harley MS 2253, fol. 73r, showing at top a two-column aaabcccb poem and at bottom a single column abab poem in long lines.

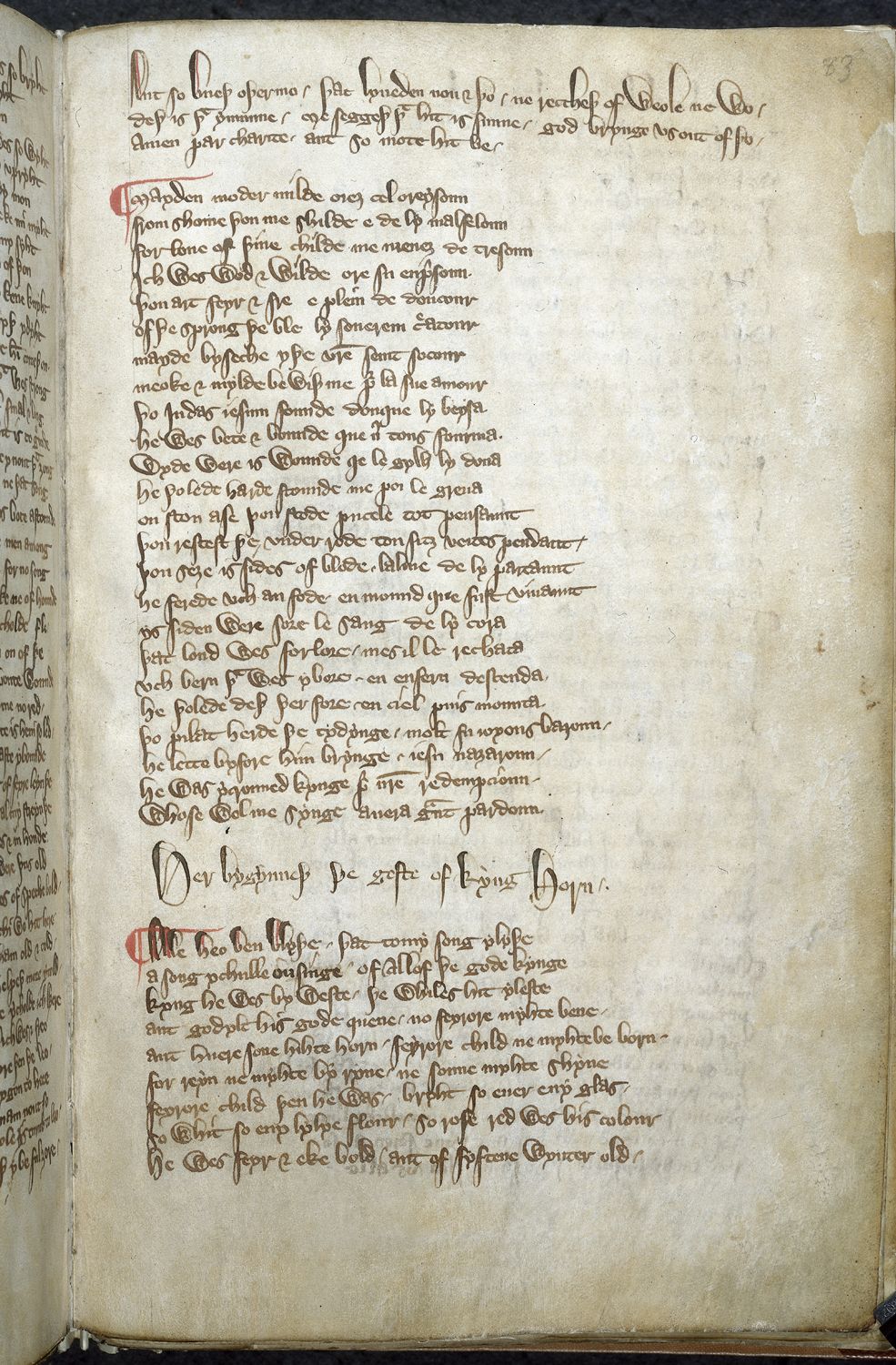

Tail-rhyme poems of various sorts are also usually written in short lines, with a verse to a line (e.g. 71v-72). Poems with more complex rhyme schemes, such as that on fol. 76 (abababddb) or fol. 63v. (aabaabbaab) are written in a block of text, with virgules separating verses. Prose texts are written out in blocks as one would expect, and such is the case with the Anglo-Norman biblical material following Horn in the manuscript. On the rare occasion where space has apparently become an issue, as on fols. 82v-83 Maximian, the scribe does change layout to suit his needs, switching from a three-column layout to prose form with virgules separating verses at the top of 83r.

BL Harley MS 2253, fol. 83r, showing at top the final lines of Maximian, written in prose form with verses separated by virgules. Below that is Mayden moder milde, abababab, and finally, King Horn, aabb, two verses to a line.

While there is much to say about the various genres and rhyme schemes and their respective mise-en-page, suffice it to say here then that there was a method to the scribe’s ostensible madness. Elizabeth Solopova has given a useful overview of several features of mise-en-page, but she frequently stops short of offering reasons for selecting particular layouts, except to observe the dominance of the rhyming couplet as a guiding principle in line arrangements (e.g. 381). In her assessment, there is much consistency in layout throughout the manuscript. So why does Horn, a poem written in aabb rhyming couplets and the longest text in the manuscript, appear in long lines with two verses to a line, violating the principles of ordinatio that the scribe had been follows elsewhere?

It might seem a trivial question, but it is one that can be explored to give us some sense of how one of the earliest poems of the “romance genre” was thought of by its audiences. Come by next week to read my take on the connection between Horn‘s genre and its layout.

Andrew W. Klein

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

aklein3@nd.edu

awklein.com

Works Cited

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2012).

Solopova, Elizabeth. “Layout, Punctuation, and Stanza Patterns in the English Verse” in Studies in the Harley Manuscript, ed. Susanna Fein (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000).

Comments are closed.