Avengers assemble!

First launched by Timely Comics 1941, and revived by Marvel in 1964, stories surrounding Captain America brought heroism to a new level as they combined contemporary needs with a superhuman figure (Howe 18). While the popularity of the Avenger may have initially been based upon his status as a World War II super-soldier, the values that he exhibits stem from a long tradition of literary heroes and are still applicable today. Arguably defined as “personal values that philosophers since ancient times have put forward as defining personal excellence,” these attributes appear throughout heroic literature time and again (White vii). In fact, on their way through literary history from Aristotle to Captain America, they even make a pit stop in the fourteenth century alliterative poem, Piers Plowman.

In a comparison of Steve Rogers, alias Captain America, and the devout pilgrim of William Langland’s allegorical dream narrative, Piers Plowman, it is clear that their values conflate on multiple levels. In this blog post, I will address three moral values. These values — drawn from the construction of Captain America and explained throughout The Virtues of Captain America: Modern-Day Lessons on Character from a World War II Superhero by Mark White — are courage, responsibility, and humility.

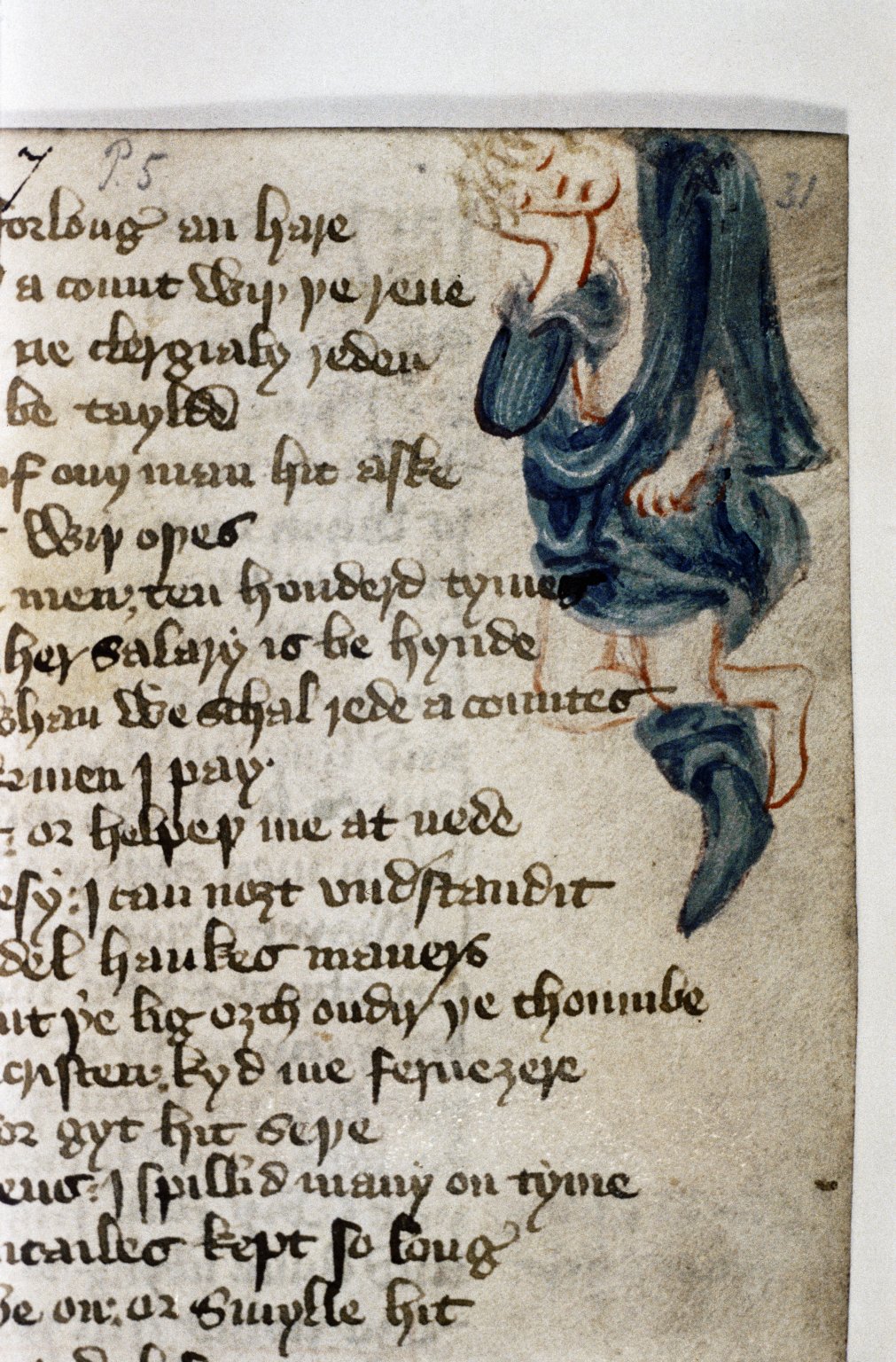

Covetousness. William Langland, Piers Plowman; England, 1427; Oxford Bodleian MS Douce 104 fol. 27r.

Covetousness. William Langland, Piers Plowman; England, 1427; Oxford Bodleian MS Douce 104 fol. 27r.

While adherence to these values runs rampant throughout Piers Plowman, I am especially concerned with Passus VIII. Throughout lines 19-111, “Perkin the Plowman” (l. 1) converses with a knight and instructs him in the art of courage in the face of temptation, responsibility to himself and those he serves, and exhibiting humility with all beings that he encounters. (It could also be said that Piers is instructing the knight on how to defend himself against such “super villains” as Covetousness, Sloth, and Hunger.)

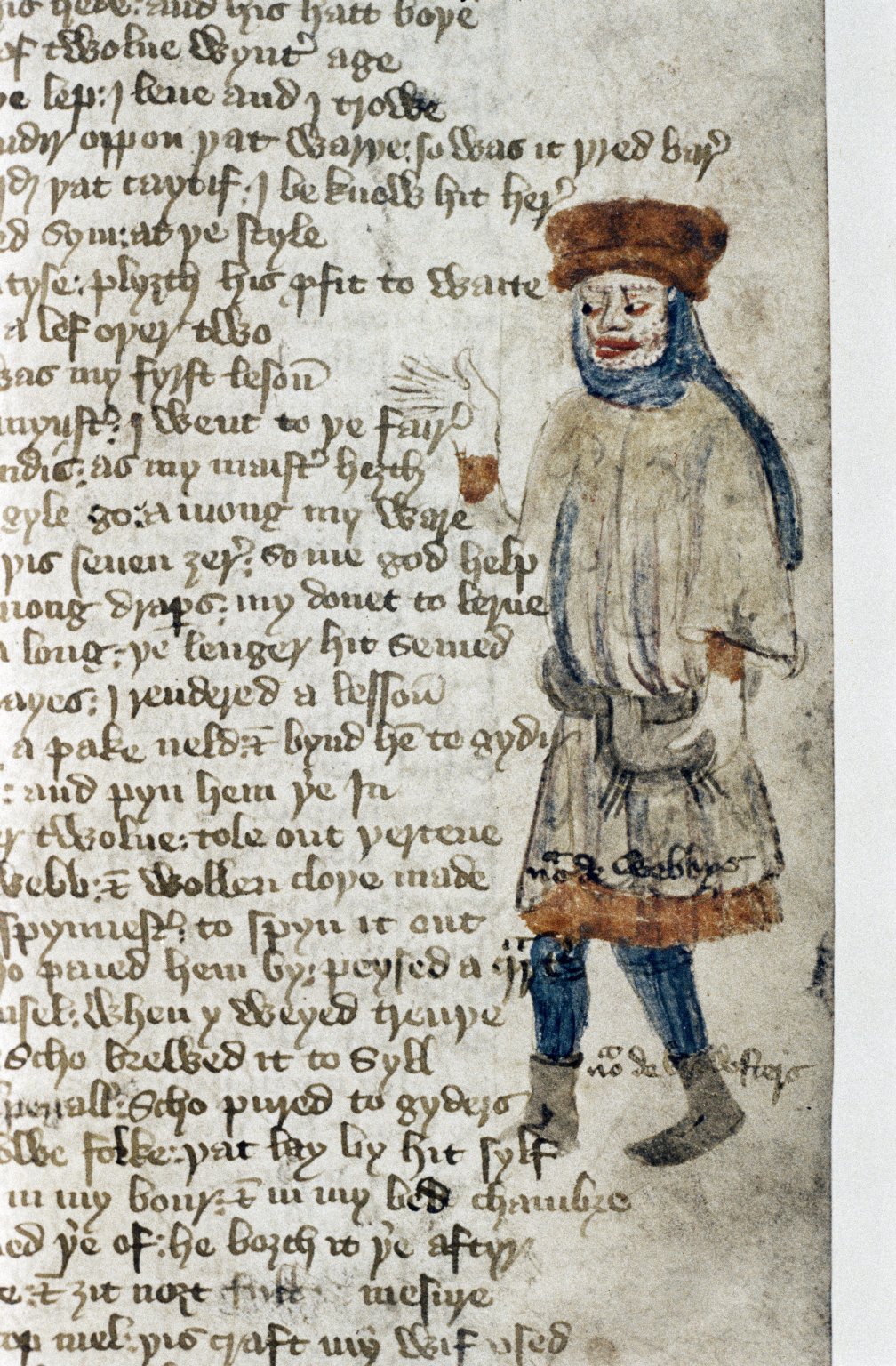

Sloth. William Langland, Piers Plowman; England, 1427; Oxford, Bodleian MS Douce 104 fol. 31r.

Thus, Piers challenges the knight to remain virtuous in the face of temptation and highlights the internal courage necessary for the promotion of pure judgement.

‘Sikerliche, sire knyhte,’ sayde Peris thenne,

‘Y shal swynke and swete and sowe for vs bothe,

And labory for tho thow louest al my lyf tyme,

In couenant þat thow kepe Holy Kerke and mysulue

Fro wastores and fro wikked men þat þis world struyen;’

…

‘And a ȝut a point,’ quod Peres, ‘Y preye ȝow of more:

Loke ȝe tene no tenaunt but treuthe wol assente;

And when ȝe mersyen eny man, late mercy be taxor

And mekenesse thy mayster, maugre Mede chekes.

And thogh pore men profre ȝow presentes and ȝyftes,

Nym him nat, and aunter thow mowe hit nauht deserue;

For thou shalt ȝelden hit, so may be, or sumdel abuggen hit.

Misbede nat thy bondeman—the bette may þou spede;

Thogh he be here thyn vnderlynge, in heuene, paraunter,

He worth rather reseyued and reuerentloker sitte:’

(Piers Plowman, ed. A.V.C. Schmidt, C.VIII.23-43)

‘Certainly, sir knight,’ said Piers then,

‘I shall toil and sweat and sow for us both

And labor for those you love all my lifetime,

On condition you protect Holy Church and me

From wasters and wicked men who spoil the world’

…

‘And still one point,’ I ask of you further:

Try not to trouble any tenant unless Truth agrees

And when you fine any man let Mercy be assessor

And Meekness your master, despite Meed’s moves

And though poor men offer you presents and gifts

Don’t take them on the chance your not deserving

For it may be you’ll have to return them or pay for them dearly.

Don’t hurt your bondman, you’ll be better off;

Though he’s your underling here, it may happen in heaven

He’ll be sooner received and more honorably seated.

(Economou pp. 70-71, ll. 19-44)

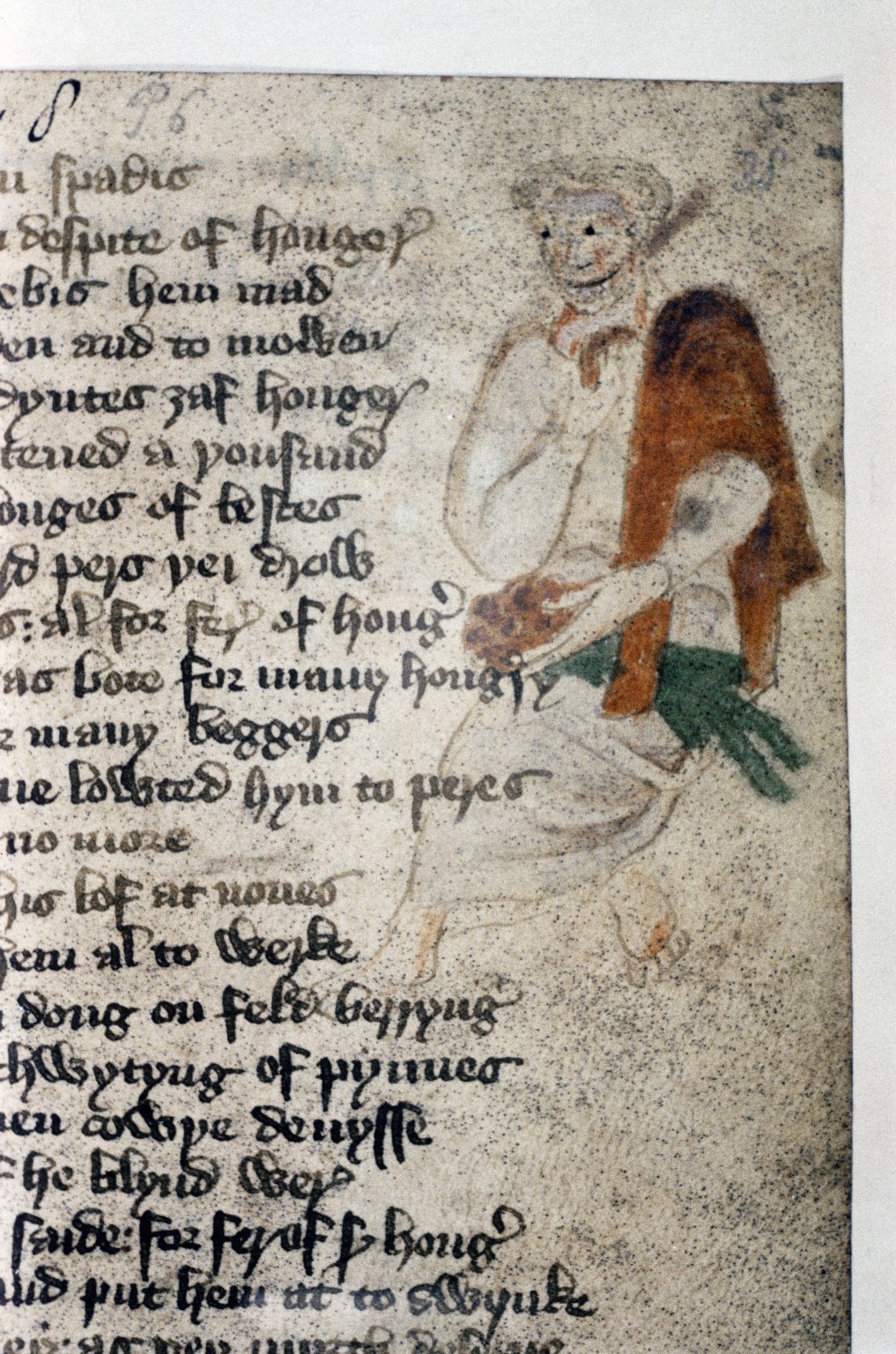

Hunger. William Langland, Piers Plowman; England, 1427; Oxford, Bodleian MS Douce 104 fol. 38r.

Ultimately, the values exhibited within this passage show that heroism does not necessarily mean that one has to be an Avenger or a devout pilgrim. Like Captain America, Piers is an advocate for the success of the common man, and their conflation proves that values and virtues can transcend both social classes and centuries. The character of Piers is manifest as a plowman instructing a knight, proving that even in the fourteenth century—and like today—virtues can be found among all social classes and depend more on personal integrity than anything else. Furthermore, as possibly the most celebrated “knight” today, Captain America proves that these values have not been lost, despite the six centuries separating his wars from those of the Piers’ compatriot. Through the success of Captain America and the entire collective of the Avengers within pop culture today, it is clear that just as these values can transcend societal levels in Piers Plowman, so too can they transcend the centuries, remaining valuable to people throughout time, and even appearing in theaters today.

Ultimately, the values exhibited within this passage show that heroism does not necessarily mean that one has to be an Avenger or a devout pilgrim. Like Captain America, Piers is an advocate for the success of the common man, and their conflation proves that values and virtues can transcend both social classes and centuries. The character of Piers is manifest as a plowman instructing a knight, proving that even in the fourteenth century—and like today—virtues can be found among all social classes and depend more on personal integrity than anything else. Furthermore, as possibly the most celebrated “knight” today, Captain America proves that these values have not been lost, despite the six centuries separating his wars from those of the Piers’ compatriot. Through the success of Captain America and the entire collective of the Avengers within pop culture today, it is clear that just as these values can transcend societal levels in Piers Plowman, so too can they transcend the centuries, remaining valuable to people throughout time, and even appearing in theaters today.

Angela Lake

MA Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Sources:

Howe, Sean. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: Harper, 2012. Print.

Langland, William, and Derek Pearsall. Piers Plowman. Exeter, UK: U of Exeter, 2008. Print.

Langland, William, and George Economou. William Langland’s Piers Plowman: The C Version: A Verse Translation.Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania, 1996. Print.

White, Mark D. The Virtues of Captain America: Modern-day Lessons on Character from a World War II Superhero. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: UK: West Sussex, 2014. Print.