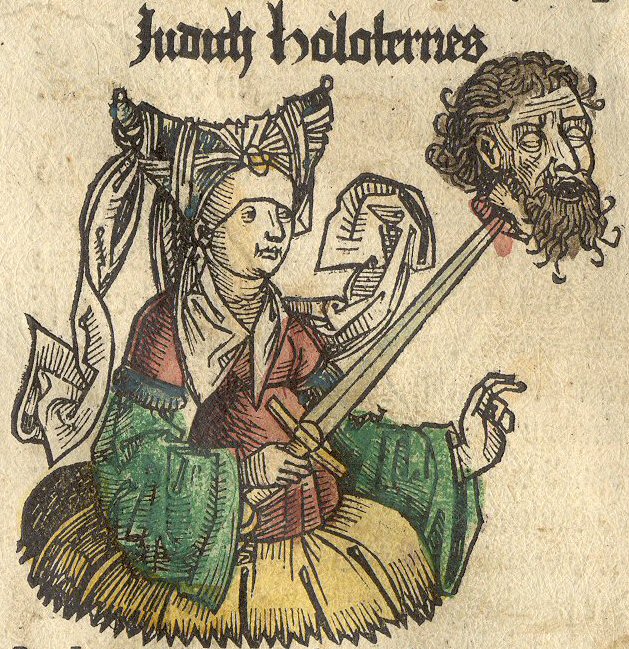

At a conference I attended earlier this month, a woman medievalist suggested we stop teaching Beowulf. It was during a session on privilege and position in medievalist pedagogy that the presenter proposed we remove Beowulf from our syllabi and replace it with Judith. She prefaced her proposal with a powerful anecdote: in preparation for reading Judith, she warned her students about encountering sexual violence in the poem. She was particularly concerned about one of her students whom she knew had been victimized, but rather than being triggered, the student said that she had felt empowered by the narrative, that Judith’s heroism helped her see her own strength as a survivor.

By substituting texts focused on male figures with those centering women’s experience, the presenter argued, we would not only be disrupting a predominantly male medieval canon but also be teaching texts that resonate more with the women in our classes. I agree that Judith deserves a place in our reading lists. But the idea that we should sacrifice Beowulf pains me because it was in the pages of Beowulf that I found myself and decided who I wanted to become.

There are many markers from my adolescence that might have signaled my proclivity for medieval studies. I grew up reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and watching Disney’s Sword in the Stone on repeat. I hoarded anything related to Arthurian legend and collected all the British folklore I could get my hands on. Although my literary preferences tended toward medievalism, my interests were rooted in Medieval England, rather than fantasy. But it wasn’t until I read Beowulf in one of my undergraduate courses that I realized how much I loved medieval literature and wanted to make my way in academia.

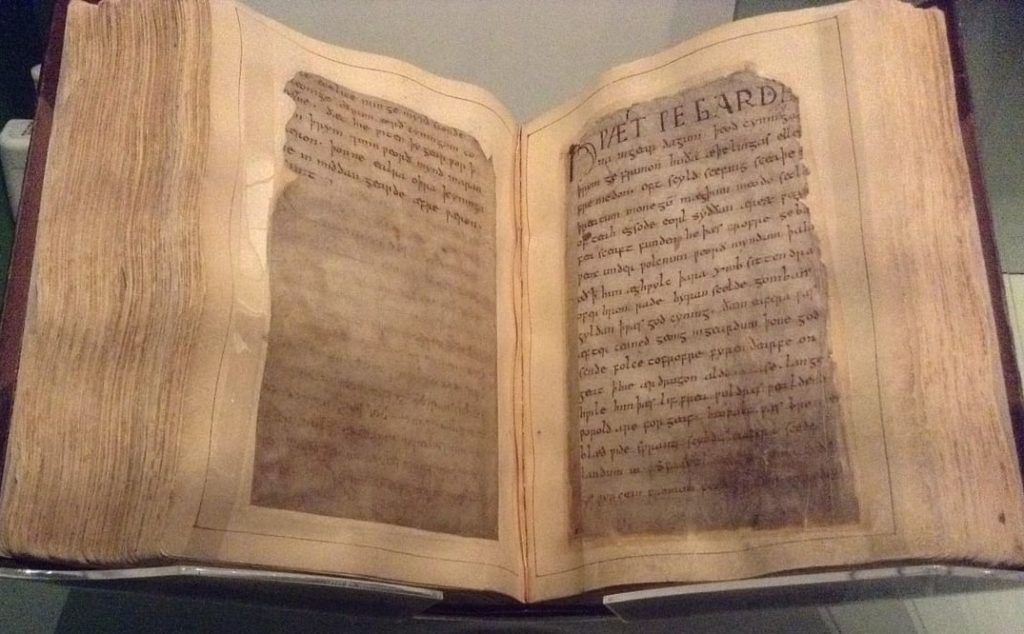

I’m a medievalist because I read Beowulf—because it gripped me and pulled me in and has never let me go. So the thought of removing it from my syllabus is, frankly, unfathomable because I remember the way it whispered to me in a language at once ancient and familiar and how it made my heartbeat feel like the echo of drums carried across so much water.

Setting Beowulf aside to center women with other Medieval English texts implies not only that its female characters are unworthy subjects of study but also that the poem does not or cannot resonate with women. Discarding Beowulf would, I think, do us all a disservice.

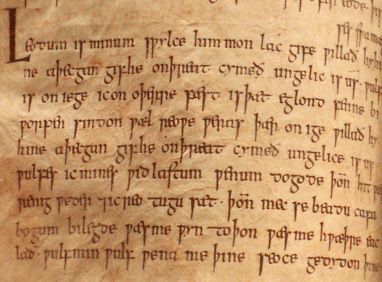

The women of Beowulf have long been relegated to the margins, a critical tradition that corroborates the misperception of the poem as both about and for men. Women medievalists, too, have been underrepresented in the adjacent scholarship. Indeed, Beowulf studies suffers from a gender problem in a way that scholarship on other iconic medieval texts does not. Women publish proportionately less on Beowulf than they do on many other texts in the Old English corpus, a disparity that does not appear to correlate with women’s limited representation in the narrative. Even The Battle of Maldon, which includes no female characters whatsoever, generates more published work by women than Beowulf does, relatively speaking. The same is true for The Wanderer, The Seafarer, and The Dream of the Rood. Women are eclipsed by men in the production of published editions and translations of the poem, as well as in their contributions to critical anthologies. I suspect that our skewed scholarly representation does not reflect a lack of interest in the poem but, rather, the extent to which we are welcomed to engage with it.

For example, Meghan Purvis, whose stunning translation was published in 2013, did not initially feel that a translation of Beowulf was a project she should undertake. In the preface to her translation, she writes, “I was in my third year of university when the professor of my History of the English Language class stood up at the front of the lecture hall and recited the opening of English’s first epic poem. The hair on the back of my neck stood up…It was because the class was taught by Professor Jennifer Bryan, and it was the first time I’d heard Old English spoken by a woman.” Purvis acknowledges that “[t]here were, of course, women already working with Old English,” but it was the experience of hearing the language of Beowulf voiced by a woman that invited her to consider that “Beowulf was a story [she] could tell.”

Like Purvis, I have also felt that Beowulf was not within my reach—as a non-traditional student who came to the story late and the language even later and as a female scholar who is keenly aware not only of the vastness of Beowulf studies but also of the academic landscape’s predominantly male and often hostile terrain. So while my singular love for the poem most certainly influences my desire to teach it, I will continue to include Beowulf in future courses because I want other women to feel welcome to find themselves in its pages.

We do not need to stop teaching Beowulf. We do, however, need to think about teaching it in ways designed to destroy the stigmas surrounding women’s interest in the text and any misconstrued ideas about gendered accessibility. Instead of eliminating Beowulf and other similarly male-centric Old English texts from our literature courses, let’s actively reflect upon how we teach these texts and revise traditional pedagogical practices that inherently center men in the canon and in our classrooms. Let’s teach the Old English Judith alongside Beowulf; The Wife’s Lament and Wulf and Eadwacer in tandem with and not simply supplemental to The Wanderer and The Seafarer.

When teaching Beowulf, let’s incorporate translations by women—whether more conservative or more creative depending upon our individual preferences and purposes. For my part, I am particularly fond of Purvis’s translation, which multiplies women’s voices, underscores their position in relation to violence, and renders Grendel’s mother visible in a way that highlights both her ferocity and her femaleness, as exemplified in this excerpt:

Grendel was torn apart, and she came looking for the meat

of her son, hanging from hooks in the ceiling.

Her home was a death-house, was becoming Grendel’s tomb;

the hell-dam came – and was she less frightening

for being a woman? – hardly. The men in the dark room

screamed out that “he” was here, too caught in pain

and fear to see the claw at the end of an arm smooth

and hairless, sharp teeth in a softer jaw.

Furthermore, maybe we focus on Grendel’s mother and the fear she evokes through her fury and her fighting skills. Maybe we review a variety of translations with our students, analyzing how and why representations of Grendel’s mother vary so greatly—from woman to monster, a mere-wyf, a “monstrous hellbride,”[1] and even Angelina Jolie.[2] Then we also teach Judith. Maybe together, she and Grendel’s mother can swallow up any remaining misconceptions about women’s proximity to Old English heroic poetry.

[1] See Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf (W. W. Norton and Company, 2000).

[2] See Beowulf, directed by Robert Zemeckis (2007).

Emily McLemore

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of English

University of Notre Dame