A few weeks ago I wrote a post introducing the Medieval Institute’s new Medieval Undergraduate Research website (now the “Undergrad Wednesdays” series on this site) and encouraging instructors to use it for course assignments that will boost their students’ Digital Humanities (DH) experience. Because DH experience has been crucial to the success of recent medievalist PhDs on the job market, this two-part follow-up post will focus on the value of DH work for them so that they can collaborate with faculty mentors to expand their online presence using this site, the Medieval Institute’s Medieval Studies Research Blog (MSRB). Whereas part 1 makes the case that more faculty should take advantage of this site’s pedagogical potential, part 2 offers specific ideas for incorporating this already active scholarly platform into graduate-level pedagogy.

For many reasons, involvement in DH is no longer optional for rising scholars specializing in the Middle Ages. Tenure-track job ads these days regularly mention DH as a desired subspecialty if not a major component of candidates’ professional profiles. As students increasingly pursue other career options, DH skills become even more important. Publishers, libraries, museums, non-profits, and university administrations rely heavily on technology, necessitating, to extend Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair’s point about DH degree programs, a newer, broader approach to professional acculturation.[1] There is, in fact, a legitimate sense of urgency behind many graduate students’ desires to pursue DH work matched by an equal level of responsibility demanded of humanities programs to support their efforts. While not all graduate students seeking DH experience intend to (or even need to) specialize in the field, they nevertheless could benefit profoundly from at least some exposure to and hands-on experience with projects that merge technology and humanities research.[2] This site offers one step in that direction, providing a digital platform backed by a major research institution that graduate students can integrate into their training from early on in their program, even at the coursework stage.

The pressures coming from the academic and non-academic job markets stem, in large part, from a growing demand for humanistic work to become more public and more accessible. Nicole Eddy, this site’s original administrator and the new Managing Editor of the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library series, points out that “academics are called on more and more to be not just scholars but Public Humanists, making a case for the significance of their work outside the academy and in new and creative ways. It is no longer sufficient to confine scholarly activity to the classroom or the academic journal, but to instead show the ability to engage with a diverse audience in creative ways.”[3] She also notes that because dissertations tend to be written for specialist audiences, contributing to projects such as this site can expand the reach and impact of our work.

In a broader sense, then, the digital humanities matter because they can deliver our work to a public audience in order to serve a wider community beyond the walls of the academy. Indeed, multiple DH practitioners have commented on the field’s ability to return us to the original spirit of humanism: “the digital humanities might yet again be set to embrace the methods and outlooks that the very first Renaissance humanists took up: to use modern communication skills–digital iterations of rhetoric and grammar–supplemented by the creative arts of the imagination and the reflective wisdom of the historical outlook to reach contemporary audiences with interpretations of what it is to be human and what it is to be a responsible citizen.”[4] With its ability to reach readers both within and without the academy, this site treats public writing as a core function of humanities work, making the relevance and value of our research more transparent.

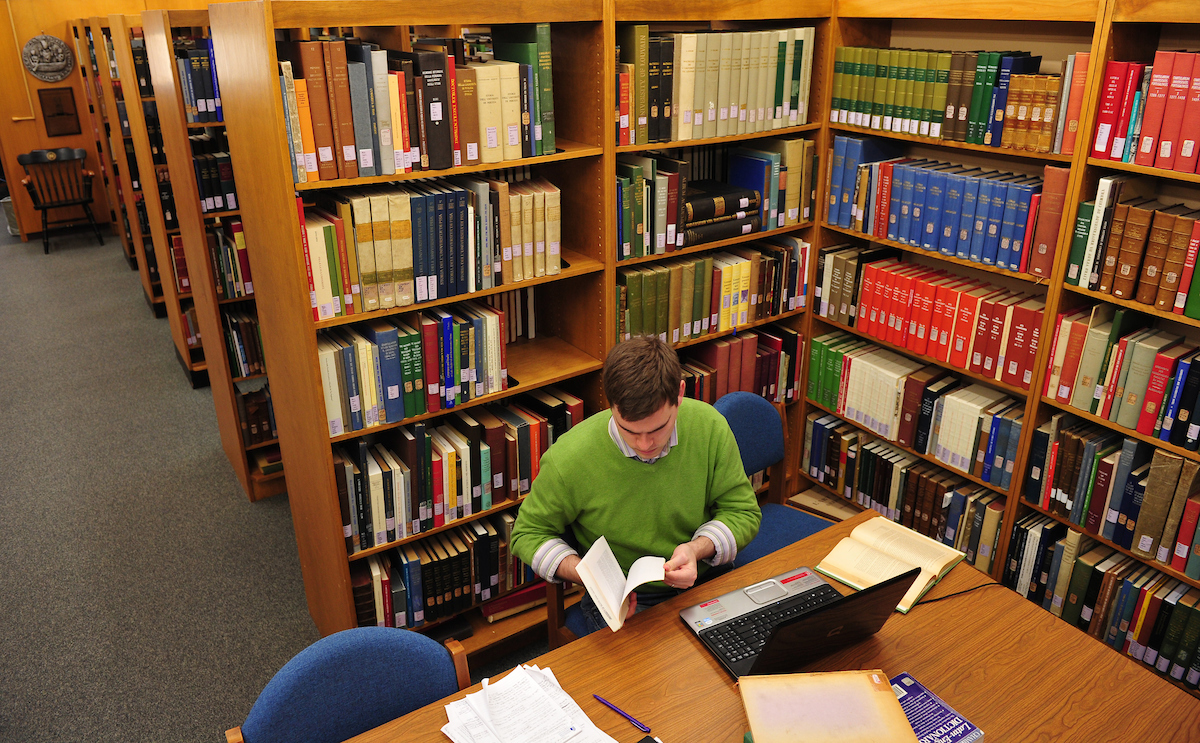

But, what, exactly, is the Medieval Studies Research Blog (MSRB)? As our “About Us” page suggests, it is an active scholarly platform for scholars at any stage of their careers. What this means is that graduate students who write posts for a course assignment contribute to a DH project that will attract immediate readers. Rather than performing a practice, or exploratory exercise, this particular professional development experience leaves students with an online publication they can list on their CV and a greater confidence in their capacity to bring research to life.

Students posting to this site share company with advanced scholars, such as Maidie Hilmo, whose groundbreaking work on the Pearl-Gawain manuscript is documented here. To our benefit, many of our visiting scholars have contributed their voices, including Richard Cole and Katherine Oswald, with even more scheduled for the coming months. Most of our posts relate to the authors’ current or recent research, written to stake a claim on a certain topic, gain a wider audience for recent publications, or develop an idea they could not fit into their last article. Others write on original topics better suited to the blog format than the academic journal, such as Andrea Castonguay’s contribution on interdisciplinarity, or to take advantage of the genre’s multimedia possibilities as in Richard Fahey’s post on South Bend. Still others write with the goal of creating supplementary background readings that undergraduates could read in their courses. Thus far, we have also created two special series– one on “Working in the Archives” and another on the “North Seas”–as well as a growing and evolving translation and recitation project. Graduate students contributing posts (or translations) to the MSRB, therefore, participate in the project as and alongside other scholars.

Depending on how instructors frame their assignments, thoughtful implementation of the MSRB in the classroom could meet multiple learning outcomes at once. The MSRB could be used to naturally integrate digital genres into our graduate students’ training in a way that helps them to craft a public as well as academic voice. By giving them the opportunity to maintain their digital presence and write for new audiences, this project can enhance their work as researchers, as instructors, as collaborators, and as public servants.[5]

For questions, posting schedules, or class visit sign-ups, feel free to contact me at kfuller2@alumni.nd.edu. Also, follow us on Twitter: @MedievalNDblog.

Part 2 of this post can be found here.

Karrie Fuller, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame/St. Mary’s College

[1] Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair, “Acculturation and the Digital Humanities Community,” Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles, Politics, ed. by Brett Hirsch (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2012): 177-211.

[2] Claire Battershill and Shawna Ross, Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom: A Practical Introduction for Teachers, Lecturers, and Students (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017): see esp. 147-48.

[3] Private correspondence. Quoted with permission.

[4] Eileen Gardner and Ronald G. Musto, The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015): 13. For a similar statement, see Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, et al., Digital_Humanities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012): 25-26.

[5] Many thanks to Erica Machulak for her detailed feedback on this post.