A website updates, a book doesn’t.

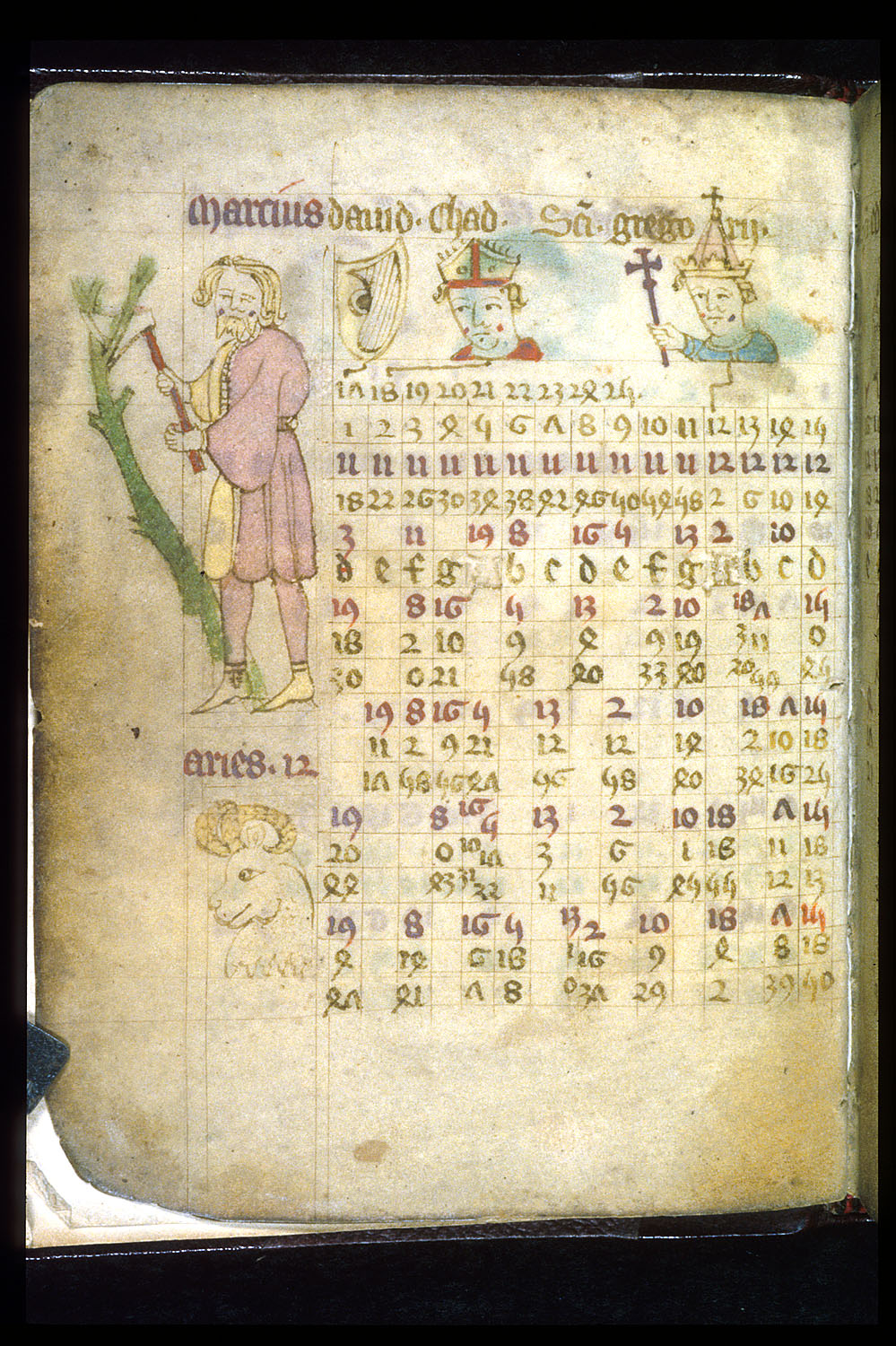

This is one of the many ways to dichotomize two of today’s major competing media. However, such a categorical binary has not always been the case, and in the medieval world books were rarely ‘published’ in the way we’ve come to understand. Take for example the manuscript British Library Harley 1758.

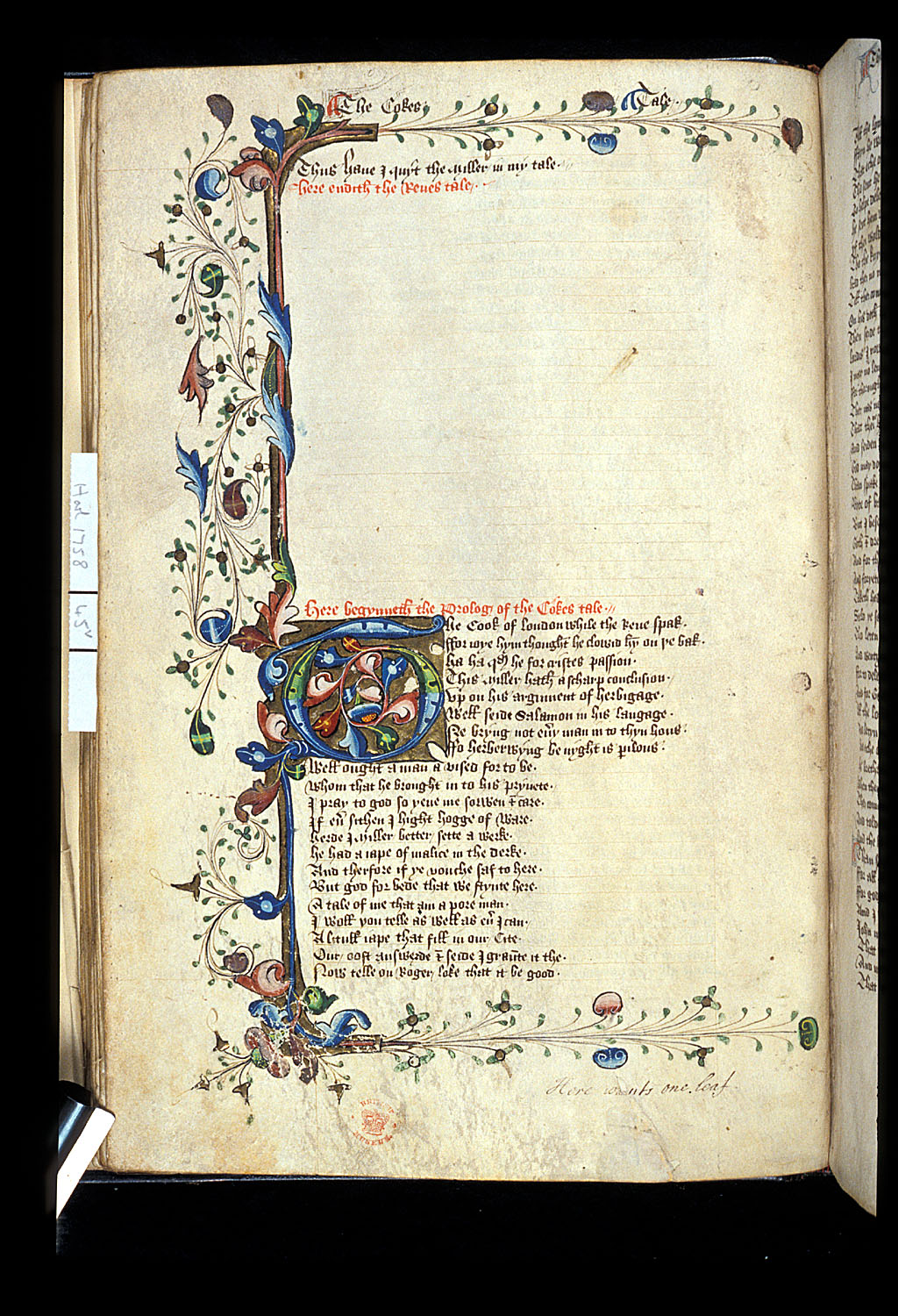

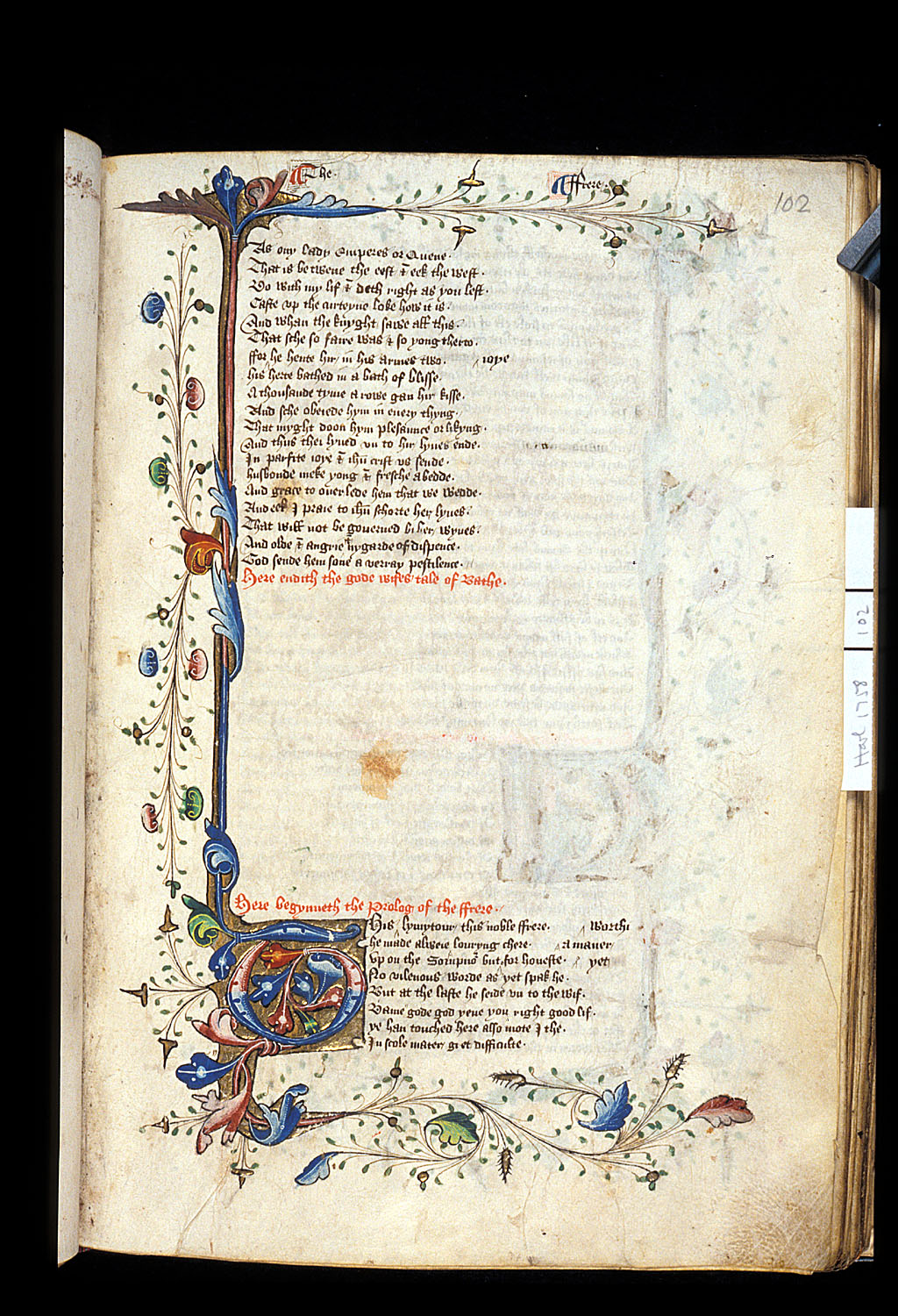

It was produced sometime between 1450 and 1500 and contains a copy of the Canterbury Tales, including the spurious Tale of Gamelyn. It seems to have been written by three distinct scribes and then corrected by a supervisor of sorts. While finely decorated and illuminated, there are notable gaps throughout the manuscript. Such gaps were clearly intentional at some stage in the process and similar blank spaces can be found in other manuscripts from the Middle Ages. The gaps in Harley 1758 (found on folios 45v, 102, 127 and 200) all fall between the end of one character’s tale and the beginning of another’s. The reason behind such premeditated gaps seems to be an intention to fill them with a portrait of the upcoming speaker. For example, on folio 102, the gap in the manuscript comes between the rubricated sentences Here endith the gode wifes tale of Bathe and Here begynneth the prolog of the ffrere.

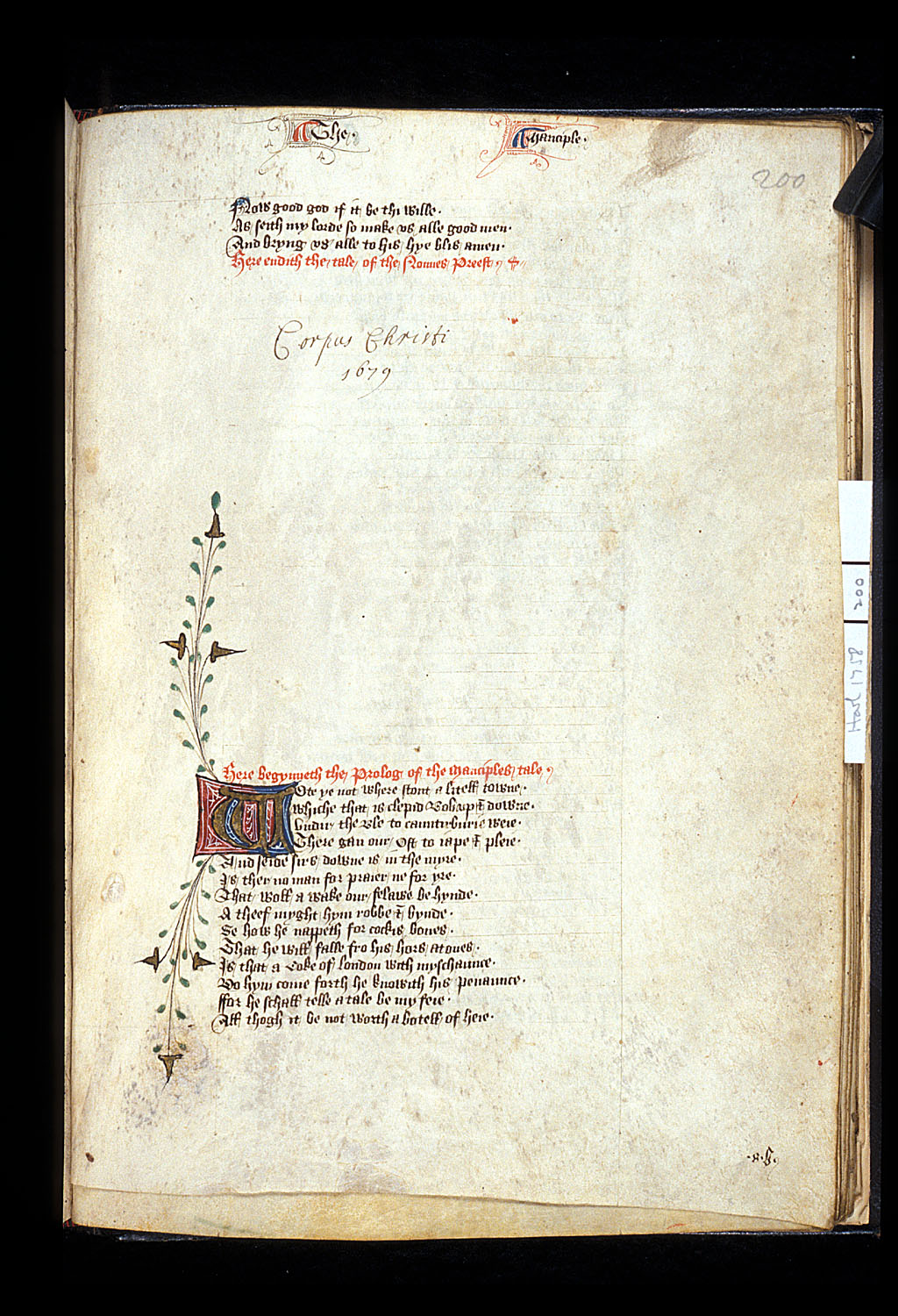

Presumably, then, the plan was to place a portrait of the Friar to fill in this gap. Similarly, on folio 200, we find a gap beginning at the top of the manuscript and ending with the sentence Here begy[n]neth the prolog of the ffrankeleyne.

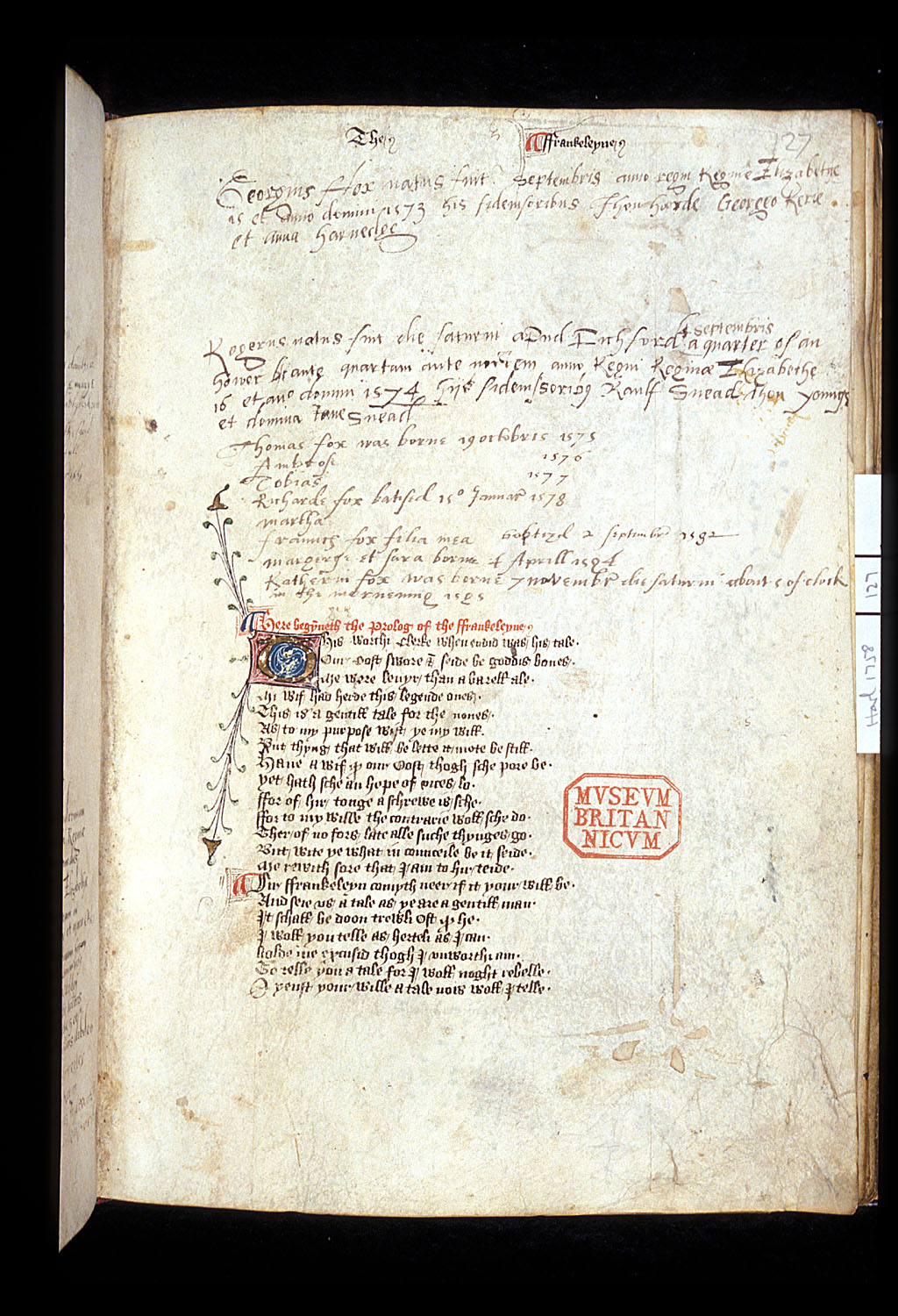

In this manuscript, portraits of the Cook, Friar, Manciple, and Franklin, were all clearly intended but have been left out in the process of manufacturing. The modern mind, strongly rooted in the print culture of the last few centuries, immediately wants to call this an ‘incomplete’ manuscript. By the simplistic standards set out above for a book, this work is clearly missing pieces intended for inclusion and therefore cannot be called ‘finished’ or ‘published’ in the sense we think of today. However, in a time with limited writing materials and a high cost of production for a single manuscript, books were an evolving entity and constantly updating in purpose and function. Moreover, as stated above, books like Harley 1758 were the product of numerous workers, all of whom had to be paid. In scenarios such as these, the eventual owners of the book funding its production might have simply run out of money. Even still, the book was ‘published’ despite its missing pieces, and its gaps cleverly used for other purposes in later times.

Folio 127 of the work has been carefully reused to record the birth dates of the children of Edmund Foxe of Ludford, a 16th century clerk. This type of genealogical information is commonly found in medieval manuscripts, since, as stated above, the preciousness of such items made them valuables in medieval and early modern times.

The gaps in Harley 1758 give us insight into medieval and early modern usage of books and thoughts on the concept of publication. It is clear that the print-age dichotomy of finished and unfinished breaks down for medieval books, and perhaps their status is more akin to modern notions of website updates.

Axton Crolley

PhD Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame