Nest (b.c.1085) was the daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr, King of Deheubarth, and the lover of the future King of England. She had three further lovers, two husbands, and potentially fourteen children. Her beauty allegedly inspired such a passion in the men in her life that it sparked a scandal that rocked the world of medieval Wales to its foundations.

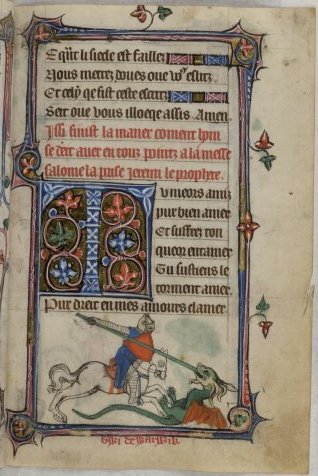

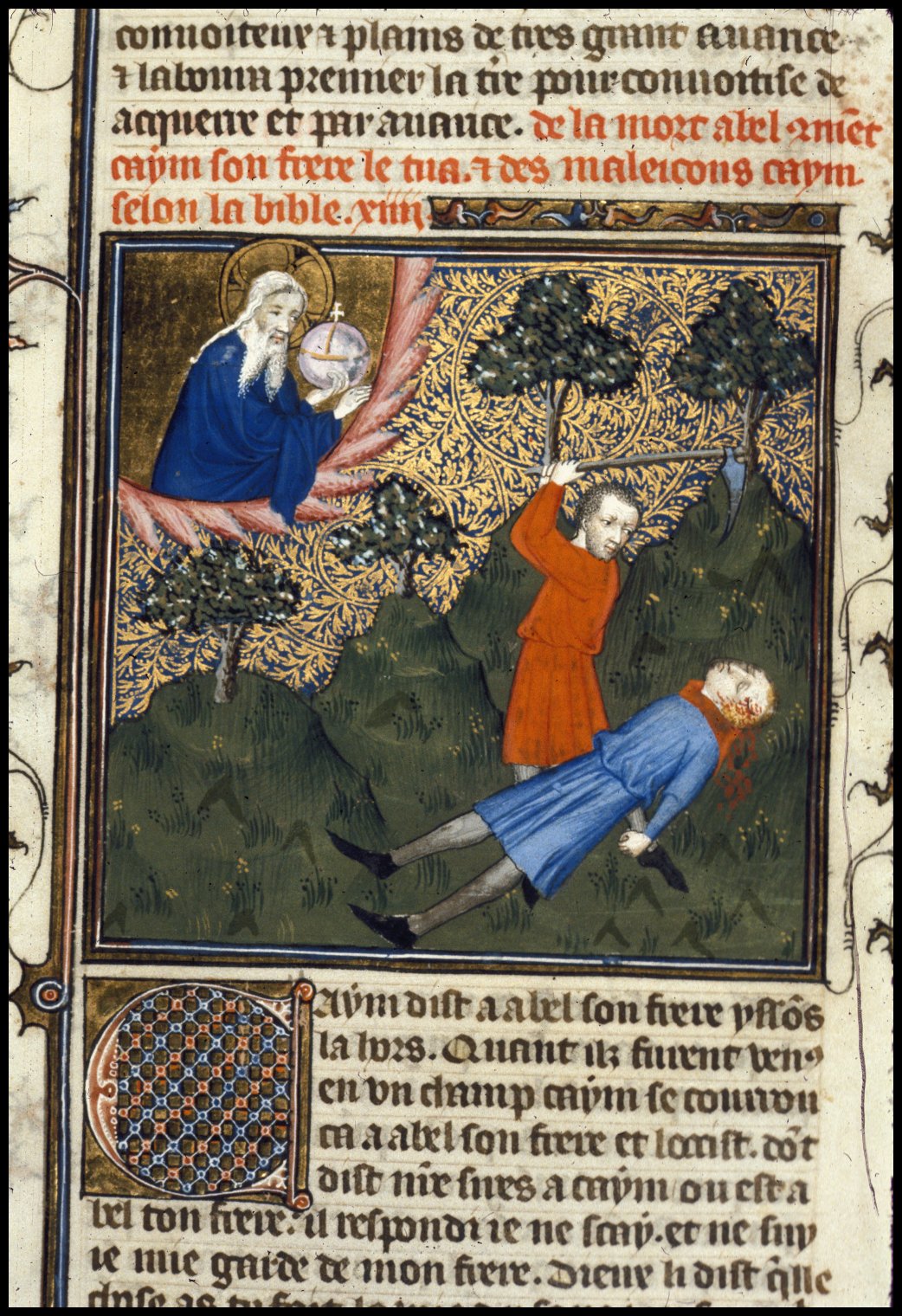

Nest was born into a troubled and often violent time, less than twenty years after the invasion by William the Conqueror and the coming of the Normans. Nest’s father died at the Battle of Brecon (1093). Left to the mercies of her Norman captors, she was possibly given to a family in the pay of King William Rufus.[1] Windsor Castle was a Royal Court Castle and a favourite haunt of Prince Henry.[2] Her later affair with Henry, the king’s brother, and her subsequent marriage to Gerald of Windsor, the son of Walter Fitz Otho, the castellan of Windsor Castle, suggest Windsor as her destination.[3]

Nest was a Welsh princess and therefore highly regarded by the Welsh people. She would thus have been a very valuable asset to the English crown, which adds fuel to the argument that she would have been taken out of Wales as quickly as possible. That being said, no attempt to rescue or to barter for her has survived in the historical record.

Some have thought Nest to be promiscuous, and indeed, historian Timothy Venning portrays her as a woman of great beauty and little virtue.[4] However, Nest was a woman of her times. With her father dead, her mother having disappeared from all reliable records, and her brothers either incarcerated or having fled to Ireland, she was thrown alone into a Norman world after the battle for Brycheiniog. That she used her beauty to charm her captors would not be unexpected; it would have been her only weapon to ensure her own comfort. Being taken to Windsor Castle would have given her ample opportunity to meet Prince Henry, a man known for his many love affairs and numerous illegitimate children.[5] Nest would have been aware that being the mistress of such a figure could have its advantages, and Henry was known to be good to his mistresses and did not refuse to recognize his bastards. An affair with Henry could offer Nest a certain security. Her life in Wales was gone, and making the kind of marriage that would once have been available to her was also gone.

With the death of William Rufus in 1100, his brother became King Henry I. During this time, the Norman lord, Gerald of Windsor, was a rising star in King Henry’s court. Being no doubt aware of the benefits of marrying a mistress of a king, Gerald did so, wedding Nest with Henry’s permission and support. Gerald had already been installed as steward of Pembroke Castle by Arnulf de Montgomery, a man who took up arms against Henry in 1102 and lost all his lands for his pains. Eventually, Henry made Gerald constable of Pembroke Castle, which brought Nest back into Wales once again.

After his marriage to Nest, Gerald went on to build castles at Cenarth Bychan (Cilgerran) and Carew, a particularly important site in the history of the kings of Deheubarth.

The date of Nest’s marriage to Gerald is open to conjecture; although, it has been suggested that she married in 1100, as proffered by John Edward Lloyd.[6] However, Gwenn Meredith suggests Nest’s first child, William fitz Gerald, was born in 1096, indicating that they were married earlier than 1100.[7] That she had one child (Henry fitz Henry, c.1105 to 1114) by King Henry I is documented; that she was the mother of Robert of Gloucester is still open for debate.[8]

Nest’s marriage to Gerald seems on the surface to have been a success. The Brut y Tywysogion, a Welsh chronicle that picks up where Geoffrey of Monmouth left off, tells us that she and Gerald had at least one son and a daughter in the nursery, along with King Henry’s son, Henry, and another son by a concubine of Gerald’s.[9] She was the wife of a now powerful lord who held Pembroke Castle, Carew Castle, and Cenarth Bychan Castle. By 1109, however, life for Nest would take a very dramatic turn with repercussions for all of Wales.

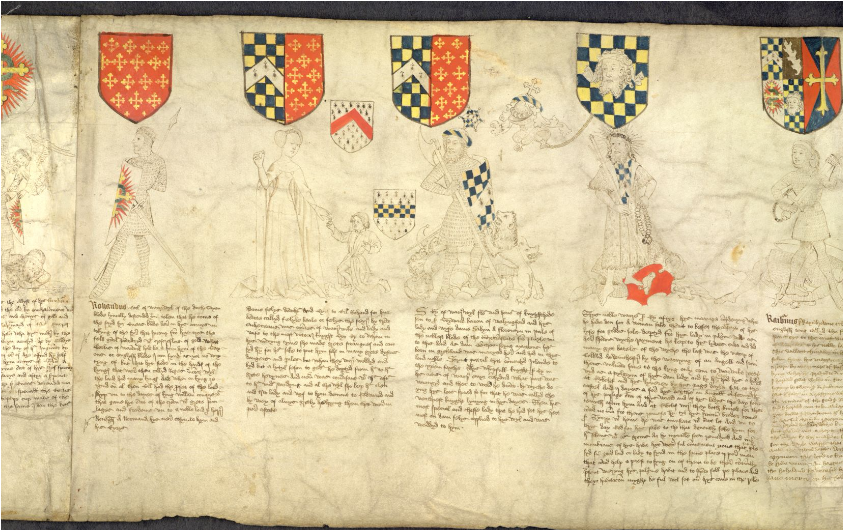

Although there was a heavy Norman influence in South Wales, many areas were still ruled as fiercely independent kingdoms warring constantly with each other. The Welsh system of partible inheritance aggravated this situation.[10] Owain ap Cadwgan, a cousin of Nest’s, was the son of Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, King of Powys. Owain’s history and that of Powys in general, as we shall see, reinforces the image of warring kingdoms and indiscriminate slaughter, which left Powys a somewhat ineffectual kingdom.[11] Cadwgan ap Bleddyn held a great feast on his lands in Ceredigion during Christmas 1109.[12] These feasts were not just Christmas celebrations, but an opportunity for princes such as Cadwgan to gauge the loyalty of their barons. Often these gatherings were used to rally support for war and were known hotbeds for political machinations and posturing.[13]

Where Gerald and Nest were at the time of Cadwgan’s feast has long been a point of discussion. R. R. Davies maintains that they and their children were at Cenarth Bychan in Ceredigion.[14]

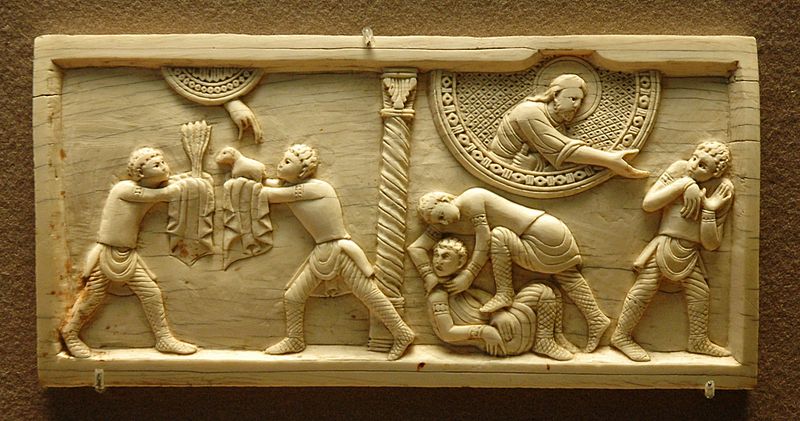

Owain and his men returned at night and dug under the castle’s foundations, scaled walls and ditches, and set buildings alight.[19] Nest, realising that Gerald would be killed if he retaliated, persuaded him not to leave the bedchamber, but to go with her to the garderobe, saying: ‘go not out the door, for there thy enemies wait for thee, but come, follow me’.[20] Once there, they pulled up the floor, and she helped him to escape down the midden chute.[21] With Gerald safely out of the way, she called out to the attackers that Gerald had gone, saying: ‘Why call out in vain? He is not here, whom you seek; surely he has escaped’.[22]

Stay tuned next week to find out what happens to Nest and her lovers...

Patricia Taylor, M.A.

University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Primary Sources

Annales Cambriae: A Translation of Harleian 3859: PRO E.164/1: Cottonian Domitian, A1: Exeter Cathedral Library MS. 3514 and MS Exchequer DB Neath, PRO E.164/1, translated by Paul Martin Remfry (United Kingdom: Castle Studies Research and Publishing, 2007).

Brut y Tywysogion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes, edited by Rev. John Williams ab Ithel, M.A. (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1860).

Giraldus Cambrensis, Expugnatio Hibernica: The Conquest of Ireland, edited and translated by A. B. Scott and F. X. Martin (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1978).

Footnotes

[1] When a woman was widowed and left with young children and their father was of noble birth, or had Crown lands, then the ‘wardship of the heir or heiress became a Royal reward.’ The children would be given to another house to be raised under their guardianship. This guardianship could be given to a royal servant. These children would live with their guardian as a part of their household, and their lands and assets would be administered by their guardians. Anne Crawford, ed., Letters of Medieval Women (Stroud: Sutton Publishers Ltd., 2002), p.108.

[2] Royal Collection Trust. press@royalcollection.org.

[3] Davies suggests that Gerald chose his wife so that “he [might] sink his roots and those of his family more deeply in those parts.’ It was not uncommon for Norman Marcher Lords to marry into the Welsh nobility in order to build their holdings within Wales. R. R. Davies, Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063-1415 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), p.106. P. A. Taylor, Nest Ferch Rhys ap Tewdwr, as final fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts, Celtic Studies (Lampeter: University of Wales Trinity Saint David, 2017), p.23.

[4] T. Venning, The Kings and Queens of Wales (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2015), p.123.

[5] Chris Given-Wilson and Alice Curteis, The Royal Bastards of Medieval England (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984), pp.60-73.

[6] John Edward Lloyd, History of Wales, Volume ii (London: Longman Green and Company, 1911), p.417.

[7] S. M. Johns, Gender, Nation and Conquest in the High Middle Ages: Nest of Deheubarth (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), p.10.

[8] Lloyd, History of Wales, Volume ii, p.499.Yorke states that Nest was ‘the beautiful mistress of Henry who brought him his eminent son Robert of Gloucester.’ P. Yorke, Esq. of Erthig (1799) and D. Williams (2016), The Royal Tribes of Wales (Hardpress Publishing, 2013), p.33. D. Crouch, ‘Nest (born before 1092, died c.1130)’, ‘Robert of Gloucester’s Mother and Sexual Politics in Norman Oxfordshire’, Historical Research vol.72. no.179 (October 1999): pp.323-333. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) [online]. Available: http://www/oxforddnb.com/view/article/19905. <accessed 10th September 2016>. [site no longer working]

[9] Brut y Tywysogion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes, edited by Rev. John Williams ab Ithel, M.A. (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1860), p.85.

[10] Lynn H. Nelson, The Normans in South Wales 1070-1171 (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1966), p.110. Partible inheritance is the system where all the sons of the deceased, and in some cases, the daughters, would receive a share of the estate. This system differs from primogeniture where only the eldest son is entitled to inherit. See the entry for ‘primogeniture’: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/primogeniture. <accessed 14th October 2016>.

[11] D. Walker, Medieval Wales (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p.38.

[12] The Brut y Tywysogion states that the event took place at Christmas 1106 (p.83). Scholars such as Lloyd (History of Wales, Volume ii, p.417) and Davies (Conquest, Coexistence, and Change, p.86) offer 1109. The Annales Cambriae state that in 1109 Owain burned Cenarth Bychan and was expelled to Ireland and makes no mention at all of Nest. Annales Cambriae: A Translation of Harleian 3859: PRO E.164/1: Cottonian Domitian, A1: Exeter Cathedral Library MS. 3514 and MS Exchequer DB Neath, PRO E.164/1, translated by Paul Martin Remfry (United Kingdom: Castle Studies Research and Publishing, 2007), p.76. Lloyd, History of Wales, Volume ii, p.418.

[13] T. M. Charles-Edwards, Morfydd E. Owens, and Paul Russell, eds., The Welsh King and His Court (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2000), p.343.

[14] Davies, Conquest, Coexistence, and Change, p.86.

[15] Cenarth Bychan Castle is now known as Cilgerran Castle.

[16] Ringwork castles are similar to motte-and-bailey castles but are encircled by lower earth walls and a ditch to enclose them which would be finished with a timber palisade. See Marvin Hull, ‘Ringwork Castles’ [online]. Available: https://www.castles-of-britain.com/ringworkcastles.htm.1995-2011. <accessed 2nd July 2018>. [site now defunct.]

[17] Brut y Tywysogion, p.105.

[18] ibid., p.105.

[19] Lloyd, History of Wales, Volume ii, p.418.

[20] ibid., p.85.

[21] P. A. Taylor, Nest Ferch Rhys ap Tewdwr, p.30. Pembroke Castle and Carew Castle both hold claim to the abduction of Nest in their tourist guides. Research considers these claims as highly unlikely.

[22] Brut y Tywysogion, p.85.