The legend of Bernardo del Carpio is one of the most problematic of Iberian epic legends. First, unlike tales based (however loosely) on heroes such as Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (el Cid) or Fernán González, there was never—as far as we know—a historical Bernardo del Carpio. Second, although four thirteenth-century versions of his deeds have survived in writing, we have undoubtedly lost at least two others. Finally, the version of Bernardo’s tale recorded in Alfonso X’s Estoria de España (EE from here on) presents contradictory information that introduces a second legend into the mix.[1] Fortunately, the EE also contains clues that allow us to hypothesize on the development of Bernardo’s story, such as mentions of their source materials and vestiges of rhyme. Furthermore, numerous geographical references, when considered visually and in conjunction with the chroniclers’ allusions to their sources, reveal insights into the now-lost versions of Bernardo’s life and deeds.

The Estoria de España’s Bernardo del Carpio

Before the EE (1270-1289), aspects of Bernardo’s legend were reported in three other texts: Lucas de Tuy’s Chronicon mundi (c. 1239), Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada’s De rebus Hispaniae (1243), and the historical introduction to the Poema de Fernán González (c. 1250). The EE is the most detailed version, including numerous episodes not reported in earlier accounts.

In the EE, Bernardo’s deeds are reported in Chapters 617, 619, 621, and 623, set during the reign of Alfonso II, King of León (791-842), and Chapters 648-52, and 654-55, set during the reign of Alfonso III (866-910). He is born from the illicit union between Jimena, Alfonso II’s sister, and San Díaz, Count of Saldaña (“Sancius” in the Latin texts). The irate King imprisons San Díaz in Luna and sends Jimena to a convent, though Bernardo is raised in the court. Although more detailed than the Latin texts, the above is the account of Bernardo’s origins also described by Lucas de Tuy and Jiménez de Rada. However, the Alfonsine chroniclers subsequently mention a contradictory story that some told “en sus cantares et en sus fablas,” or in their songs and tales (Alfonso X 351). Bernardo is again illegitimate, though his mother is Timbor, sister of Charlemagne, who is enticed by San Díaz while making a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela.

As an adult, Bernardo joins forces with Marsilio, Muslim King of Zaragoza, in the victory over Charlemagne’s troops at Roncesvalles. He is later made aware of his lineage through a game of backgammon, which prompts his first failed request for his father’s freedom.

The hero next appears in Alfonso III’s reign. He is an invaluable knight, aiding the King in victories over Muslim armies at Benavente, Zamora, Polvorosa, and Valdemora. The hero then plays a crucial role in the victory over French troops at Ordejón, defeating his cousin, Bueso. After each battle, Bernardo requests his father’s freedom, which Alfonso consistently denies.

The following year, a confrontation between Bernardo and the King leads to the hero’s banishment. Bernardo founds El Carpio and ravages Salamanca and surrounding areas, until Alfonso agrees to release San Díaz in exchange for the fortress. However, they soon discover the Count has died. The hero is subsequently presented with his father’s corpse and is again exiled. He travels France, where he is received by Charles, his uncle, though rejected by Timbor’s son, his half-brother. Dejected, he returns to Spain; conquers Aínsa, Berbegal, Barbastro, Sobrarbe, and Montblanc; and settles near the Canal de Jaca, where he marries and spends the remainder of his life.

Mapping the legend of Bernardo del Carpio[2]

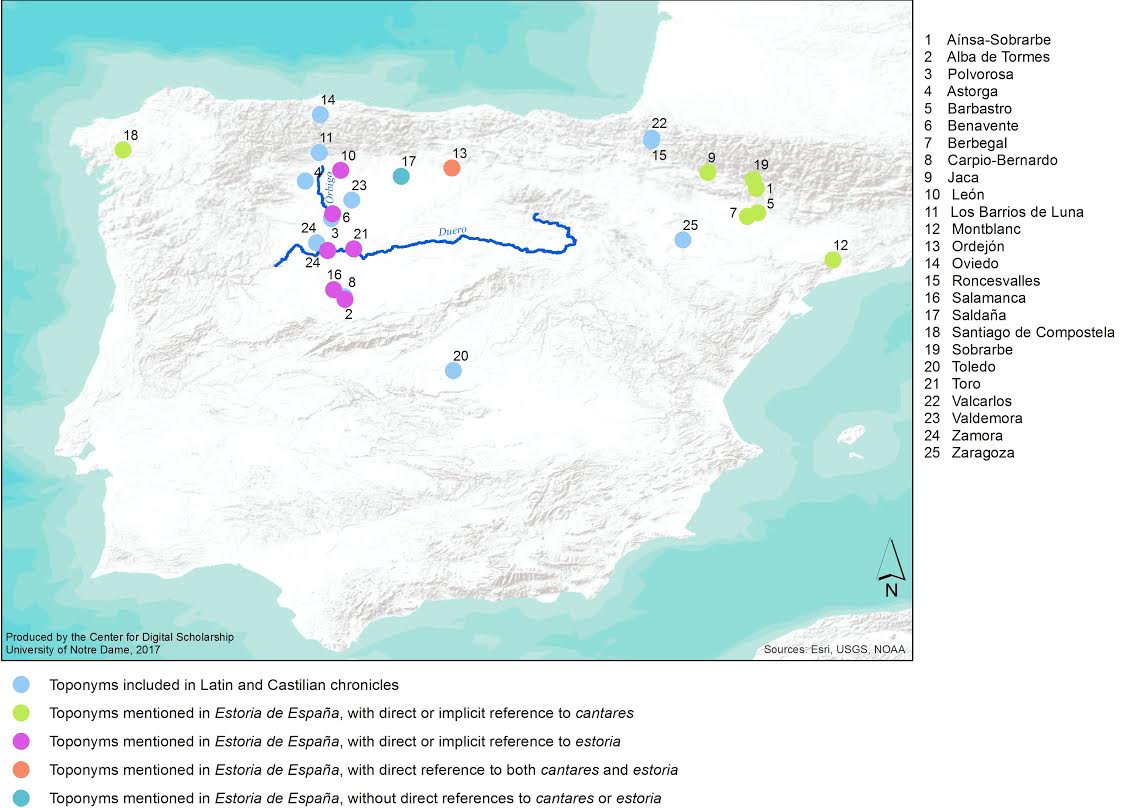

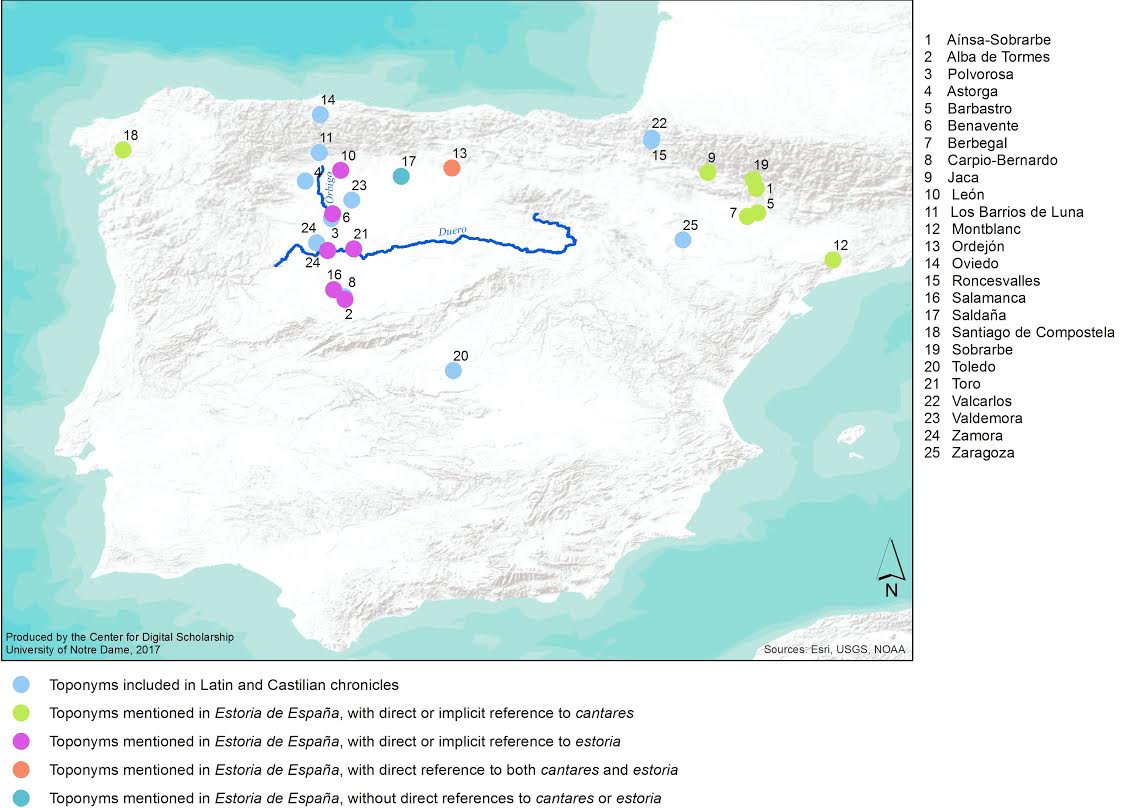

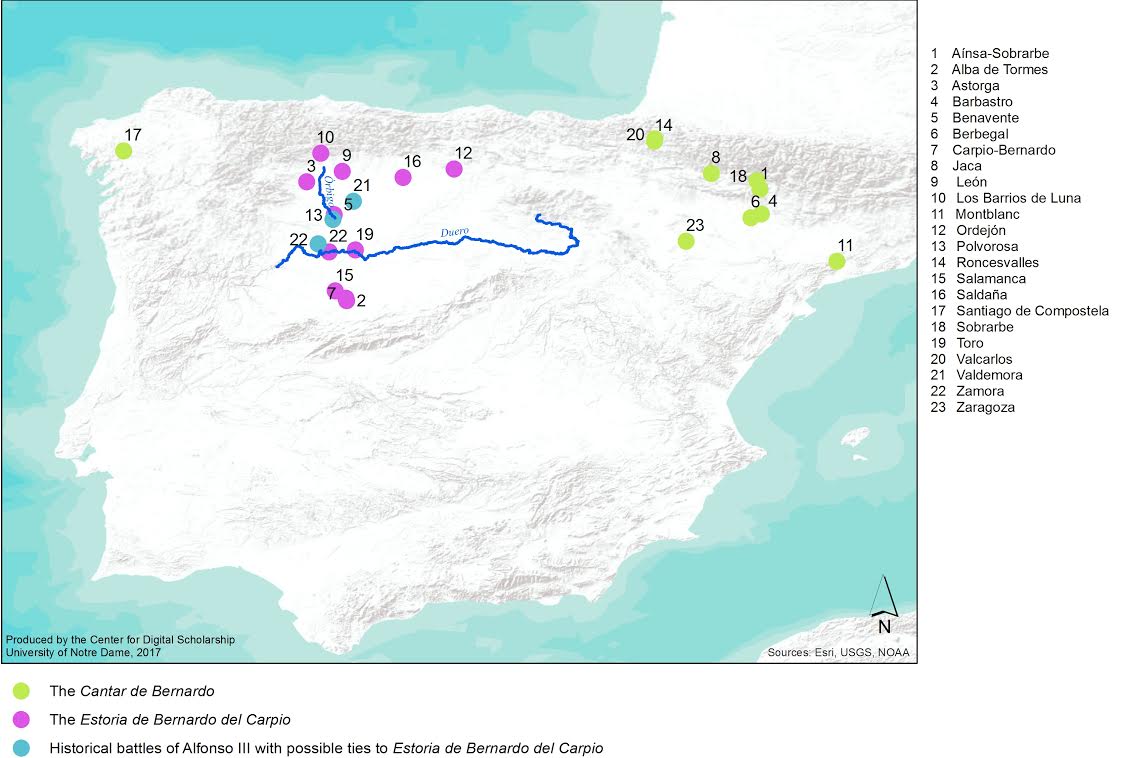

In their retelling, the Alfonsine chroniclers mention at least 25 place names. On the following map, the locations mentioned have been categorized into five groups. The first consists of the toponyms that are mentioned across all three chronicles. The next four refer specifically to the EE: toponyms linked directly or indirectly to cantares; those linked to an estoria; those linked to both cantares and an estoria; and those with no reference to either cantares or an estoria.

At first glance, two regions stand out: the vertical strand stretching from north to south in modern-day Castilla y León and that stretching across the Pyrenees. With a few exceptions, the geographic dichotomy also reflects a division in source materials. Of the points stretching from north to south in Castilla y León, the estoria is mentioned frequently; on the other hand, direct or implicit references to the cantares abound in the Pyrenean region. I will center the remainder of my discussion around these now-lost cantares.

In the EE, the chroniclers reference cantares about Bernardo four times:

- His birth to Timbor (sister of Charlemagne), who meets San Díaz along the Camino de Santiago and accompanies him to Saldaña (Alfonso X 351)

- The battle against Bueso at Ordejón (371)

- The return of San Díaz’s corpse at El Carpio (375)[3]

- Bernardo’s experience in the French court and subsequent conquests (375-76)[4]

When these episodes are considered with respect to the toponyms included on the above map, four outliers stand out: Roncesvalles and Zaragoza, for their lack of reference to the cantares; Ordejón, for its geographic distance from other localities connected to cantares; and El Carpio, for the thematic disparity between the return of San Díaz’s body and other episodes associated with cantares. While Ordejón is a curious case, I omit it from this discussion, as the chroniclers reference both cantares and an estoria as they report the battle against Bueso.

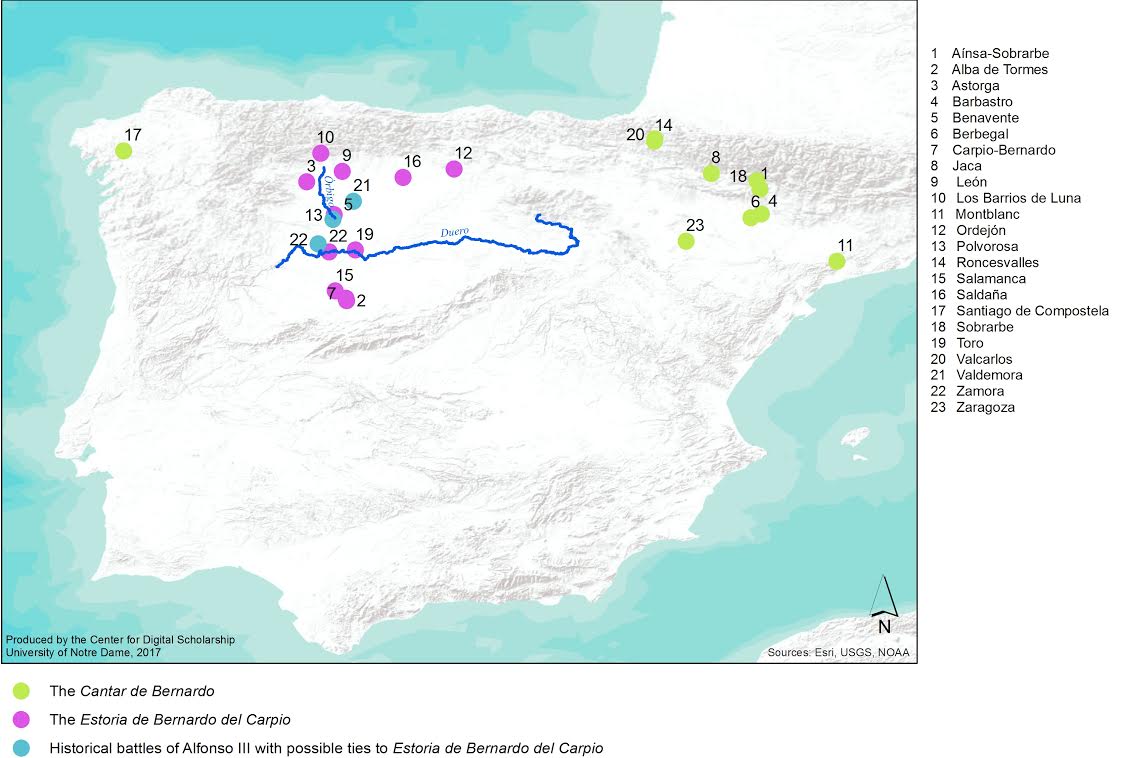

Regarding Bernardo’s alliance with Marsilio, King of Zaragoza, and the battle of Roncesvalles, the Alfonsine chroniclers do not mention cantares. Rather, they rely on the Chronicon mundi and De rebus Hispaniae, following the Latin versions faithfully and citing them frequently. However, drastic differences between Lucas de Tuy’s and Jiménez de Rada’s accounts of Roncesvalles and those of their predecessors—not the least of which is Bernardo’s presence in the battle—suggest there existed at least one other source that included Bernardo at Roncesvalles. Considering the hero’s ties to Charlemagne and France, it is possible that some version of Roncesvalles figured into the materials that related Bernardo’s birth to Timbor, his battle with Bueso, and his altercation with his half-brother at the French court. In the following map, therefore, Roncevalles and Zaragoza are classified among episodes pertaining to at least one cantar de gesta about Bernardo, which I term the Cantar de Bernardo.

The delivery of San Díaz’s corpse presents an entirely different issue, as the chroniclers reference the cantares in an episode with no apparent connection to any other incident linked to such sources. Rather, the details relate to Bernardo’s conflicts with Alfonso III. Given that neither the Count of Saldaña’s imprisonment nor El Carpio coincide with any other incident connected to the cantares, it is unlikely that the Cantar de Bernardo included the delivery of his father’s corpse. A plausible alternative is that the incident pertained to an independent, episodic cantar that centered on the conflict between Alfonso and Bernardo. The chroniclers’ reference to their sources also hints to the independent nature of this cantar: instead of mentioning only the cantares, the chroniclers reference both romances and cantares: “Et algunos dizen en sus romances et en sus cantares…” (Alfonso X 375). Such terminology perhaps served to differentiate the source that narrated the delivery of San Díaz’s body from the repeatedly-cited cantares. As such, despite a reference to the cantares, I do not include El Carpio among toponyms associated with the Cantar de Bernardo.

Consider the revised map:

While there are other important outliers that I will not discuss here (such as Ordejón), reclassifying Zaragoza and Roncesvalles among episodes linked to a Cantar de Bernardo and omitting the delivery of San Díaz’s corpse from such Cantar further illustrate the bipartite nature of the Alfonsine Bernardo del Carpio. On the one hand, we have the illegitimate nephew of Charlemagne consistently at odds with his French relatives, whose tale—set in the Pyrenean region—would have been known through at least one cantar. On the other, we have the illegitimate nephew of Alfonso II, who repeatedly battles his uncle due to his father’s perpetual incarceration. His tale would have been set in present-day Castilla y León and would have been known through an estoria. When the toponyms of such sources are mapped, we have the visual representation of two independent tales that eventually merged to form what we now know as the legend of Bernardo del Carpio.

[1] Given the contradictory details, scholars have generally agreed since Jules Horrent’s 1951 La Chanson de Roland dans les littératures française et espagnole au moyen âge that the EE’s version of the legend of Bernardo del Carpio is, in fact, a compilation of two independent legends.

[2] Thank you to Matthew Sisk in Notre Dame’s Center for Digital Scholarship for his tremendous help in putting these maps together.

[3] Despite this direct reference to the cantares, El Carpio is mentioned in all three chronicles (though the episode in question only appears in the EE), and is categorized on the map as such.

[4] Although the chroniclers do not directly reference the cantares during their description of Bernardo’s conquests after leaving the French court, the details appear to continue the episode initiated upon the hero’s confrontation with his half-brother. That, along with the fact that such details do not stem from either Latin chronicle, make a connection with the cantares plausible.

Katherine Oswald, Ph.D.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish

University of Notre Dame

Works cited

Alfonso X, el Sabio. Estoria de España. Ed. Ramón Menéndez Pidal (Primera crónica general de España que mandó componer Alfonso el Sabio y se continuaba bajo Sancho IV en 1289). Vol. 2. Madrid: Gredos, 1955.

Horrent, Jules. La Chanson de Roland dans les littératures française et espagnole au moyen âge. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1951.

Jiménez de Rada, Rodrigo. Opera Omnia, Pars I. Ed. Juan Fernández Valverde. Brepols: Turnhout, 1987.

Lucas de Tuy. Chronicon mundi. Ed. Emma Falque. Brepols: Turnhout, 2003.

Poema de Fernán González. Ed. Itzíar López Guil. Libro de Fernán Gonçález. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2001.