While Valentine’s Day is still weeks away, Wales celebrates lovers with St. Dwynwen’s Day (in Welsh, Dydd Santes Dwynwen) on January 25th. The tradition similarly invites exchanges of cards, flowers, and heart-shaped gifts as expressions of love and affection. The holidays also share medieval origins, but St. Dwynwen’s Day derives from a darker story.

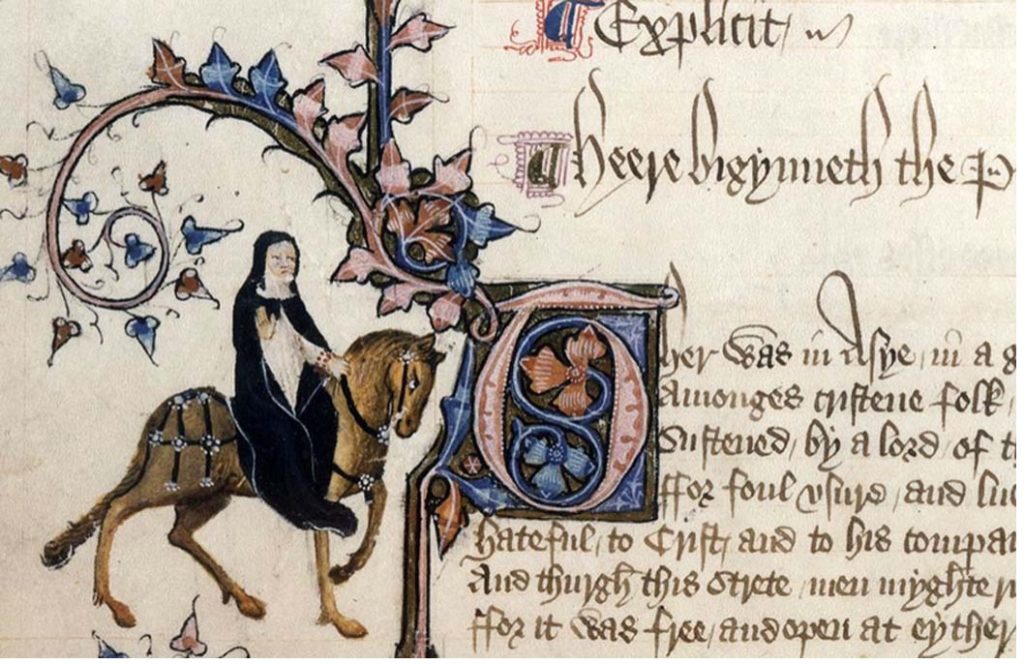

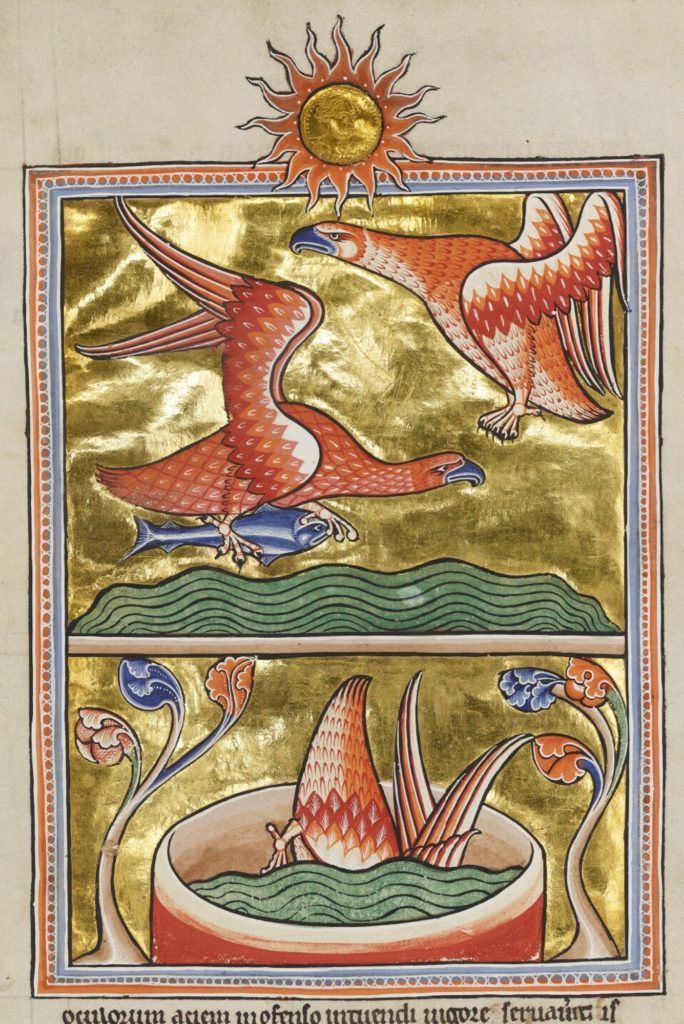

As a Chaucerian, I am always delighted to share that the earliest association of Valentine’s Day with romantic love in English literature appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules – that is, Parliament of Fowls or, more plainly, Parliament of Birds.[1] The dream-vision poem, written in Middle English between 1381 and 1382, describes the speaker’s encounter with a congregation of birds who come together on St. Valentine’s Day to select their mates:

For this was on Seynt Valentynes Day,

Whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make,

Of every kynde, that men thynke may;

And that so huge a noyse gan they make

That erthe and see, and tree, and every lake

So ful was that unethe was there space

For me to stonde, so ful was al the place (Chaucer 309-15).[2]

[For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day when every bird of every type that one can imagine comes to choose his mate, and they made a huge noise, and the earth and sea and trees and every lake are so full of birds that there was hardly any space for me to stand because the entire place was filled with them.]

That the mating activity of the birds takes place on the medieval feast day of St. Valentine is not entirely coincidental, nor is it exactly a correlation of St. Valentine’s Day with romantic love as we recognize it today. In the Middle Ages, birds were believed to form breeding pairs in mid-February, so the date simply makes sense. At the same time, Chaucer’s pairing of the birds in a beautiful garden during springtime recreates the setting for courtly love typical of medieval romance narratives. Now, of course, the notion of romantic love resounds through any mention of the word valentine.

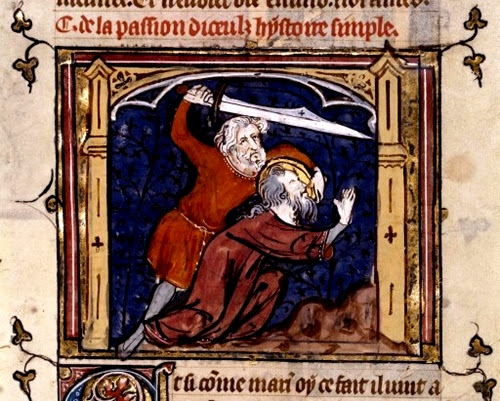

Like so many other martyrs, the story of St. Valentine is not as pretty as the poem that ascribed hearts and flowers to his namesake. He was executed by beating and beheading on orders from the Roman emperor Claudius II on February 14 in 270 AD. Two centuries later, the date of St. Valentine’s martyrdom became the date of his annual feast day, the date to which Chaucer refers in his poem. From the late Middle Ages onward, Valentine’s Day has been synonymous with romantic love, somewhat regardless of St. Valentine’s circumstances.

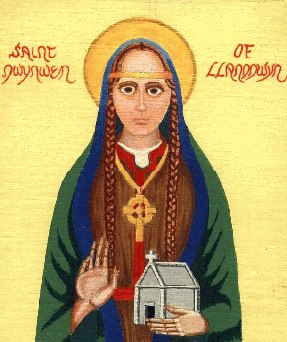

The tale of St. Dwynwen, from which the lesser-known Welsh celebration of lovers derives, departs markedly from both the martyrdom of St. Valentine and the light-hearted poem that set his feast day’s romantic tradition in motion. There are several variations of her story, all of which date Dwynwen, or Dwyn, to the 5th century as the daughter of a semi-legendary Welsh king.

The National Museum of Wales describes Dwynwen as the loveliest of King Brychan Brycheiniog’s 24 daughters, who fell in love in Maelon Dafodil. But her father betrothed Dwynwen to another man, and when Maelon learned that Dwynwen could not be his, he became enraged. He raped Dwynwen and abandoned her.

Distraught, Dwynen ran to the woods and pleaded with God to make her forget Maelon, then fell asleep. An angel came to Dwynwen, delivering a drink that erased her memories of Maelon and transformed him into ice. God then granted Dwynwen’s three wishes: that Maelon be thawed, that she never be married, and that God grant the wishes of true lovers. As a mark of gratitude, Dynwen dedicated herself to God and spent the rest of her days in his service.[3]

The details of what transpired between Dwynwen and Maelon differ. Some versions of the story say that Dwynwen refused Maelon’s sexual advances, which resulted in her rejection but not her rape. The entry on Dwynwen in the Iolo Manuscripts: A Selection of Ancient Welsh Manuscripts, states that “Maelon sought her in unappropriated union, but was rejected; for which he left her in animosity, and aspersed her.”[4] Other versions say that Dwynwen was in love with Maelon but did not want to marry him because she wanted to become a nun, or was forbidden to marry him and became a nun; they do not say that she was raped. But Maelon’s anger appears across her story’s retelling, often accompanied by allusions to its physical manifestation – for example, “Maelon was furious, taking out his anger on Dwynwen.”[5]

When it comes to romantic love, Dwynwen does not thrive in her endeavors; instead, she tends to suffer in her story, typically at the hands of men. Indeed, the Welsh poet Dafydd ap Gwilym, writing during the 14th century, remarks upon how Dwynwen was “afflicted yonder by wretched wrathful men.”[6] Often it is the very man who is supposed to love her who inflicts her suffering.

St. Dwynwen is not a martyr in the traditional sense. In short, she does not meet her demise, like St. Valentine does, as a result of her religious beliefs. She does, however, ask God to absolve her of any memories of the man she loves, and by sacrificing this part of herself, she secures a blessing for lovers in return. Despite its darkness, perhaps St. Dwynwen’s story does not seem so strange an impetus for a lovers’ celebration after all.

Dwynwen suffers. She survives. She’s sainted. Certainly, she deserves as much recognition as a bunch of birds.

Emily McLemore, Ph.D.

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

[1] Valentine, n. Oxford English Dictionary.

[2] Geoffrey Chaucer, Parlement of Foules, The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry D. Benson, Houghton, 1987.

[3] St Dwynwen’s Day, National Museum of Wales, accessed 20 Jan. 2023.

[4] Iolo Manuscripts: A Selection of Ancient Welsh Manuscripts, translated by Taliesin Williams, The Welsh MSS. Society, 1888, p. 473.

[5] Santes Dwynwen, Welsh Government, accessed 20 Jan. 2023.

[6] Iolo Manuscripts, p. 473.