In the thirteenth-century Roman de Silence, patriarchal inheritance laws of the land drive a young girl’s parents to make a choice: lose their lands and leave their daughter without an inheritance or raise her as a boy.[1] Thus, the child (aptly named Silence) grows up to become one of the greatest knights of the realm. In a society that values masculinity, the female characters in the story strive to assert their voices in a world dominated by men’s discourse. The story begins as a traditional chivalric romance, with Silence’s mother Eufemie (whose name means ‘use of good speech’ (cf. euphemism)) and father Cador struggling, in the passionate heat of their courtship, to say what they feel. When Silence reaches puberty, and Cador stresses the necessity of maintaining a masculine identity, Silence, whose body has become the locus for a battle between the personified forces of Nature and Nurture, is left with little choice but to acquiesce. Later, living quite successfully as a man and the most valued knight of King Evan’s (spelled, in various ways, Ebain in the original) court, Silence faces the unwanted sexual advances of King Evan’s wife, Eufeme (whose name means ‘alas! woman’), at which point, things begin to unravel. Unable to voice an essential, personal truth and trapped by the confines of traditional gender roles, Silence ultimately is left silent in a story that is both beautiful and devastating. In 2017, revisiting this story of a transgender protagonist, sexual harassment (and assault), that which is spoken, and those who are silenced, I knew that the time was ripe for introducing my students to Silence.

The course was structured informally as a reading group, meeting once a week over lunch in my classroom. We had about thirty students participating in one way or another throughout the semester with a core of about a dozen who attended regularly. I initially planned for about eight meetings. We read 1,000 lines a week of Sarah Roche-Mahdi’s facing-page translation, moving fairly slowly through the text.[3] While this pace allowed us to dive more deeply into Silence during our meetings, we decided that we wanted to continue the conversation outside of class through an online discussion board using our school’s learning management system. This included topics such as “Silence’s Birth and Youth,” “Silence, the Minstrels, and Eufeme,” and (because I teach teenage girls) the spirited catch-all, “Things That Have Us Shook.”

My goal with this reading group was, in part, to take young, pre-college students and turn them on to that undeniably electric attraction so many of us feel when we study the Middle Ages. In part, I also wanted them to get fired up about how little has changed since thirteenth-century France in conversations about identity and politics. It was serendipitous, then, that a month before our first meeting, TIME magazine named the “Silence Breakers” its “Person of the Year,” celebrating women for breaking their silence in the face of sexual harassment and assault. The weekend before our first meeting, celebrities in the film and television industries at the Golden Globe Awards coordinated the launch of the #TimesUp movement (building on the momentum of the #metoo movement, which had been gaining significant traction through the winter). Women who had been silenced by their abusers and the systems that protected them were speaking out—breaking their silence, just as our Silence could not. My students were incensed and energized—you have to work in a girls’ school to understand it—it was in the air and in many of the conversations they were having with each other and begging to have with me. Silence, then, was a fitting literary entrée into the conversation.

The Roman de Silence explores some challenging topics, including sexual harassment, consent, gender dynamics (including transgender issues and the politics of gender), Nature vs. Nurture, and a problematic narrator. Because I was working with students of a wide range of ages (the kids in my group ranged from ages 14-18), I wanted to be sensitive to that dynamic. We decided it was necessary to establish a common language, most important to the students, agreeing on what gender pronouns to use in reference to Silence, the main protagonist, and Heldris, the ostensible author and narrator.[4] One of the biggest (and coolest) challenges with the Roman de Silence is the dexterity with which Heldris moves back and forth between genders in reference to Silence, sometimes even within the same sentence. Heldris, too, is ambiguous in gender, so how were we to refer to our author/narrator? In the end, the students decided together that they would use the gender neutral “they” in reference to both, which provided a sometimes stumbling, but always insightful frame for our discussions. It matters, they learned, which pronouns we choose when referring to Silence and to Heldris.

Early in the story, Heldris establishes their authority by claiming that they will write the story in French based on their reading of a “Latin version” of unclear origin:

I’m not saying there isn’t

a good deal of fiction mingled with truth,

in order to improve the tale,

but if I am any judge of things,

I’m not putting in anything that will spoil the work,

nor will there be any less truth in it,

for truth should not be silenced. (1663-8)

So, very quickly, my students had to figure out how to hold these two things in tension: how can truth and fiction coexist? First, we have an author who is grounding themselves in textual authority (Latin, no less!). On the other hand, that author freely admits that, just as one might a bland soup, they have spiced up the tale by mixing in fiction “in order to improve” it, but in a way that will not spoil the work or make it less truthful. This metaphor of cooking (which seems to lie just below the surface of Heldris’s words) helped my students, but it also sowed the seeds of doubt for some—how reliable was this narrator? Whose side were they on?

Choosing to use the singular “they” in reference to Heldris throughout our discussions ended up highlighting (sometimes rather strikingly) the author’s problematic position of authority. When divorced from gender identifiers, assumptions students might otherwise have made about Heldris’s opinions or positions suddenly unraveled, making them much more complex (and perhaps for my students, more frustrating). One minute, Heldris seems so intimately conversant in the effects of sexual harassment on a female victim. The next, they’re condemning women wholesale for their tendency to manipulate men with their tears. When we removed our essentialist biases about how women write or men write (and where their sympathies lie as writers), we found ourselves so much less sure about how to understand Heldris’s position.

Here’s an example from the online discussion board “Things That Have Us Shook.” We had been reading about Silence’s prowess at tournaments and on the battlefield. Heldris describes Silence as “a second Alexander,” running through a heroic catalogue of their clothes and especially helmet (like the shield of Achilles). Eufeme, who at this point already has attempted to sexually assault Silence once, will soon begin plotting to do so again, despite Silence’s revulsion of her:

Student A: What does it suggest about sexuality if Silence has been raised as male for all intents and purposes and yet is not attracted to women? It seems like an extremely progressive idea that even today older generations seem to have trouble grasping.

Student A later explained in our meeting that she was trying to think through the idea that a male-presenting person, raised with all the trappings and cultural baggage of a man, might be, if not attracted to women, presumably attracted to men. For this student, this allowed for fluidity among gender and sexuality that really struck her and made her feel like Heldris was pushing some boundaries in exciting ways. Then, her peer responded thus:

Student B: I actually didn’t read it as a progressive idea, as the phrasing of the encounter between Eufeme and Silence seemed to imply that Silence was not attracted to Eufeme because they (Silence) were biologically female. In this context, the book could be interpreted as hetero-normative, because despite Silence being raised as male, their “true nature” as female means Silence cannot be attracted to women. I guess it really depends on what Heldris thinks Silence identifies as (I personally think Silence is bi-gender, but Heldris seems to be on the side of Nature).

This sparked a lively group discussion about Heldris’s “allegiances,” as the students called them. Silence is the best at combat—as a woman, they can do everything men can do (and better!), but Heldris still will make snide comments about women and point back to the Nature vs. Nurture debate. Then again, Heldris so carefully plays with Silence’s pronouns in a way that seems to suggest, in Student A’s words, “maybe Heldris chose to switch pronouns when Silence felt more in tune with one gender over the other.” This seems so sensitive and gentle that when at other points Heldris makes blanket statements about the failings of women, such statements felt particularly brutal to my students. While the students loved the debate between Nature and Nurture—so dramatic, so steeped in stereotypical gender norms, and so very relevant to cultural discussions we’re having today—they had difficulty figuring out just where Heldris fell on the debate.

We spent quite a bit of time discussing the threats and execution of both sexual and deadly violence on women’s bodies. It took us a full meeting, for example, to begin to unknot King Evan’s dismissal of Eufeme’s accusations of sexual assault against Silence (fabricated as they were). When the king says to his wife, “So let’s pretend it didn’t happen. Just think of it all as a dream, sweetheart. / Nothing happened, nothing’s wrong, nothing should come of it” (4245-7), we couldn’t help but think about Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, and so many others, and the many men who worked behind the scenes to enable their predation. When Heldris says of women who are trying to avenge the wrongs done to them: “When she is told to keep quiet, / she tries all the harder to make noise” (4270), we couldn’t help but hear the “Silence Breakers.” When King Evan has Silence stripped of all their clothes in front of the court, exposing King Evan’s limited understanding of truth and forcing Silence, in quiet dignity, to speak their own and then fall silent, my students mourned the loss of Silence’s ability to own and live their identity. In the end, Nature’s victory rung so terrifying (in all its objectification of Silence) that we were reminded of the recent horror film Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele (as though Silence had been sent to the “sunken place” and were watching their life, silently, from afar). This is part of what inspired my students to want to dramatize the story in film.

I said previously that I had planned for this group to last about eight weeks. Most of these meetings focused on close, textual analysis and consideration of other primary and secondary texts. During one meeting, I brought in a .pdf of a working draft of Regina Psaki (University of Oregon) and Bonnie Wheeler’s (Southern Methodist University) new prose translation of the Roman de Silence. Wheeler said of the translation: “Gina and I originally conceived of this project as one that would be in print but have now decided to make it open-access on-line so that it can be used in classrooms without adding to student book costs. Thus we don’t want it included in course packets, etc., for which students are charged.” They asked a few colleagues (including myself) who teach at different levels to do beta testing, and their goal is to produce a parallel text/translation, including links to important essays on the poem. If all goes well (and they find a great tech-helper), we should expect to see it available by spring 2019. In the meantime, my students were delighted to engage with (and even provide suggestions for) this fantastic translation-in-progress.

About six weeks in, my students decided that they wanted to produce a film trailer for a movie about Silence (it was a group filled with budding actors, costume designers, creative writers, and film makers) and began making plans in a Google doc for a culminating project. They spent about four weeks on this and developed a draft for a script. What was most interesting was how they thought through the rhetoric, purpose, and audience of a film trailer and struggled with what scenes to preview and how best to problematize Heldris (who would provide the extradiagetic voiceover). In the end, they ran out of time (with graduation looming on the horizon), but during our final meeting (lucky number 15), they were determined to come up with some kind of project nevertheless. Therefore, they created a Twitter handle, which this year’s students will now run. So feel free to check out @heldriscornwall on Twitter for some fun memes, surveys, retweets, and recommended reading![5]

Jennifer Boulanger, Ph.D.

The Hockaday School

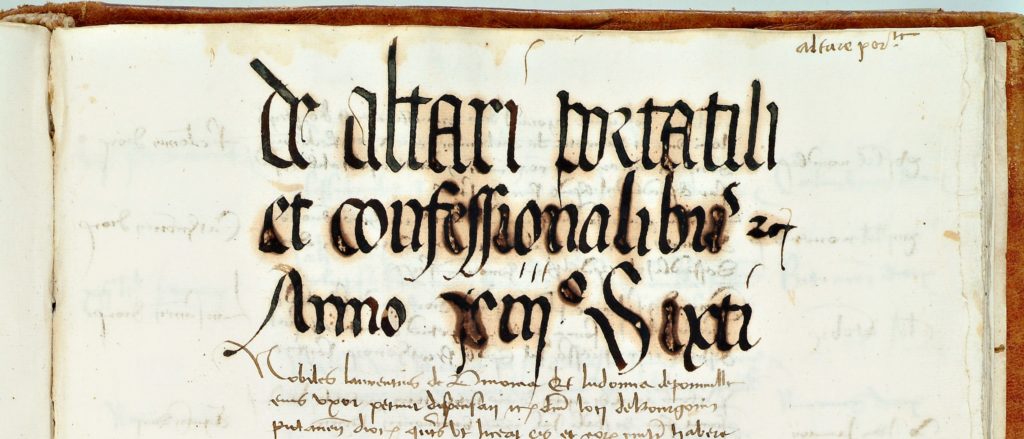

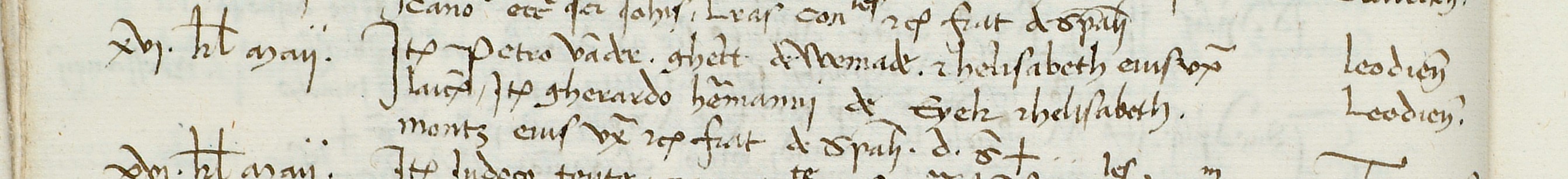

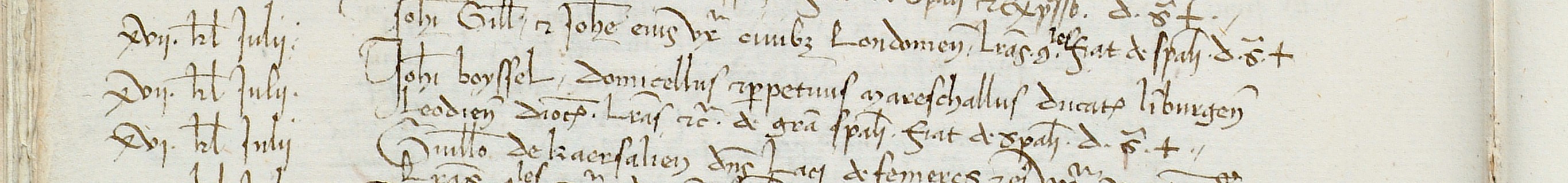

[1] Our only copy of the text is in University of Nottingham, MS Mi.LM.6, which now has a new shelf mark as part of the Wollaton Library Collection: MS WLC/LM/6. A catalogue record can be viewed here: http://mss-cat.nottingham.ac.uk/DServe/record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=wlc%2flm%2f6. Further manuscript bibliography can be found here: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/collectionsindepth/medievalliterarymanuscripts/wollatonlibrarycollection/wlclm6.aspx. The manuscript was unknown until 1911 when it was discovered at the Elizabethan manor house of Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire in a crate labeled “unimportant documents.” See pp. 221-36 of the Report on the Manuscripts of Lord Middleton Preserved at Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire, compiled by W. H. Stevenson for the Historical Manuscript Commission (London, 1911).

[2] Images can also be viewed here: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/heritage-digitisation/gallery.aspx.

[3] See Heldris de Cornuälle, Silence: A Thirteenth-Century French Romance, ed. and trans. Sarah Roche-Mahdi (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1992).

[4] The name Heldris de Cornuälle translates to Heldris of Cornwall, but it could also be Heldris of Cornouaille, the medieval name for a region in south-west Brittany, the southern part of the modern-day département of Finistère. It is probably an Arthurian-sounding nom de plume of sorts. We know nothing about the author. The language in the manuscript is a mix of Francien and Picard dialects of Old French, meaning that the manuscript was likely brought from France to Nottingham, possibly during the Hundred Years’ War (Roche-Mahdi xxiii).

[5] For further reading, Arthuriana has dedicated two full volumes to the Roman de Silence (7.2 and 12.1). More recently, see: Katie Keene, “‘Cherchez Eufeme’: The Evil Queen in Le Roman de Silence,” Arthuriana 14.3 (Fall 2004): 3-22; Heather Tanner, “Lords, Wives, and Vassals in the Roman de Silence,” Journal of Women’s History 24.1 (Spring 2012): 138-159; Jane Tolmie, “Silence in the Sewing Chamber: Le Roman de Silence,” French Studies 63.1 (January 2009): 14-26.

The fifteenth-century hagiography of Elisabeth Achler, a Franciscan tertiary from Reute, ascribes to her the standard catalogue of proper saintly elements. She could almost be the exemplar of a late medieval holy woman. But her hagiographer, Augustinian prior Konrad Kügelin, does not stop with standard recitations of virtues and somatic spirituality. In almost every category, Achler is said to exceed even the most frenetic reports of her role models’ own deeds.

The fifteenth-century hagiography of Elisabeth Achler, a Franciscan tertiary from Reute, ascribes to her the standard catalogue of proper saintly elements. She could almost be the exemplar of a late medieval holy woman. But her hagiographer, Augustinian prior Konrad Kügelin, does not stop with standard recitations of virtues and somatic spirituality. In almost every category, Achler is said to exceed even the most frenetic reports of her role models’ own deeds.