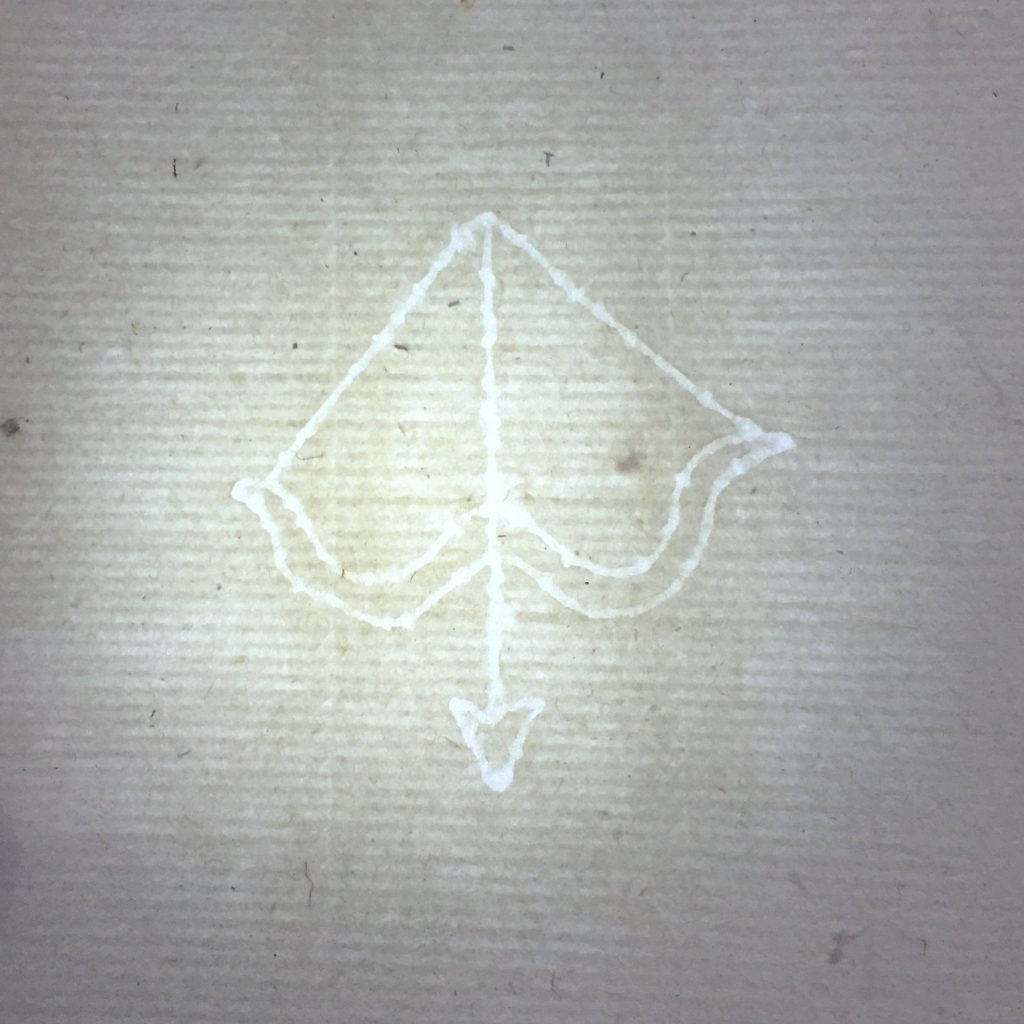

Riddles and runes go together, at least in some of those found in the medieval codex known as the Exeter Book of Old English poetry (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501).

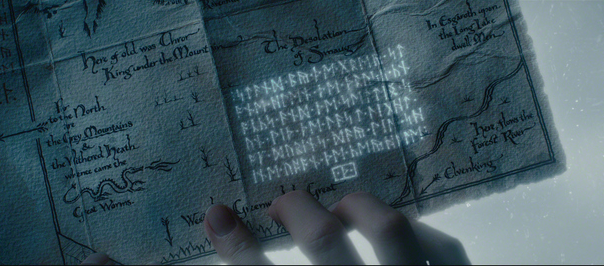

J. R. R. Tolkien puts their cryptic association to creative use when, in The Hobbit, the dwarves’ map reveals to Elrond in runic ‘moon-letters” a riddle describing how King Thorin Oakenshield’s company will discover the secret door and enter the Lonely Mountain of Erebor once they arrive to reclaim their stolen treasure-hoard from the dragon Smaug.

As with Tolkien’s moon-letters, runes found in the Exeter Book Riddles serve to both obscure and illuminate their riddle and its solution. This is to say—if you are literate and can read the runic alphabet—you have an important clue to solving the puzzle. If not, the riddle’s solution is even further obscured from the solver.

While certainly not every Exeter Book riddle contains runes, and indeed most do not, there is a higher frequency of runes in riddles than elsewhere in the extant corpus of Old English poetry, suggesting that perhaps runes offered something useful to the playful, puzzling, at times comical, Old English riddle.

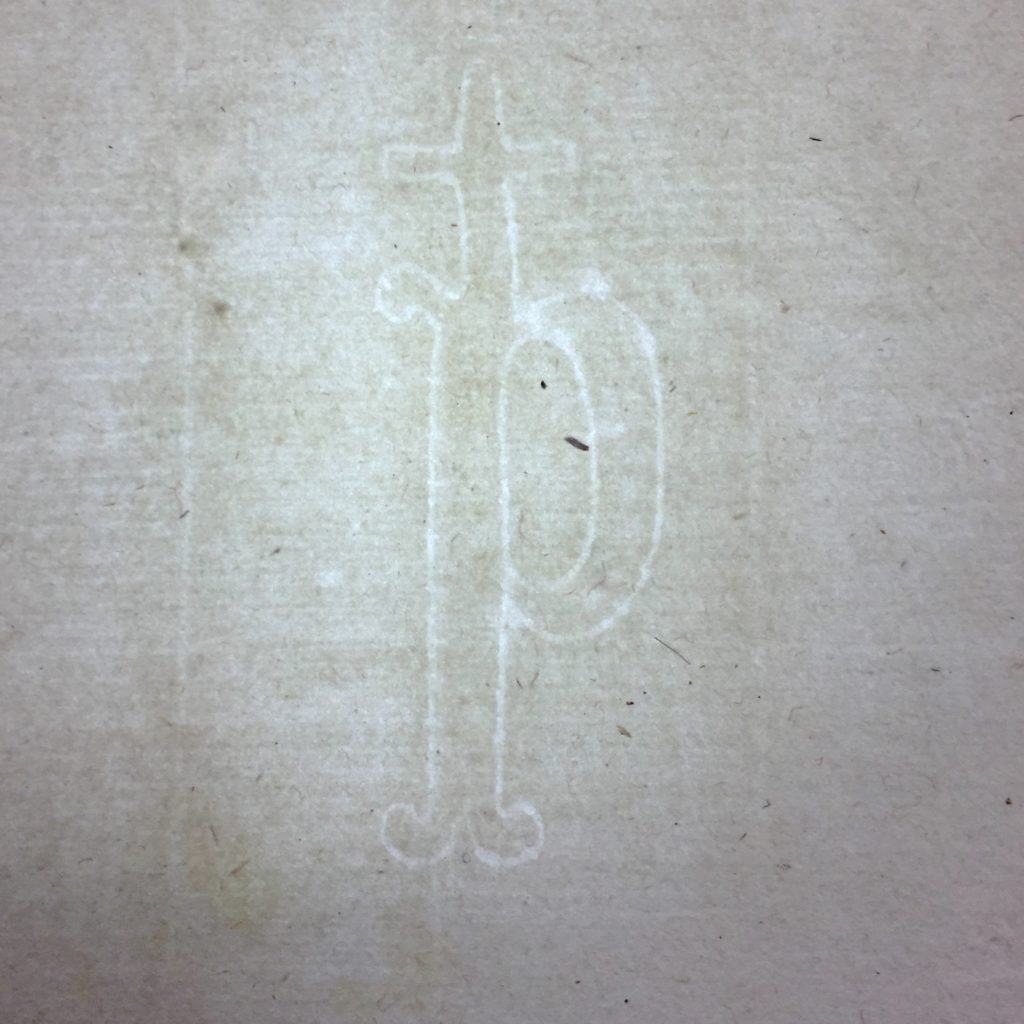

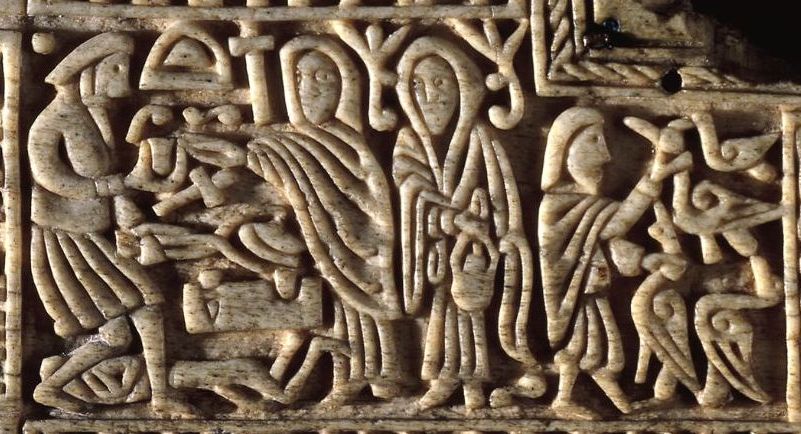

Moreover, there is a general instability in the consistency of runic characters, and this further adds another enigmatic layer of obscurity to a riddle, since no runic standard of writing—or carving—ever truly existed in any standardized form. Rather, form and style of runic inscriptions (as well as the orientation of runic characters) varied wildly in medieval England and Scandinavia, which makes reading runes especially difficult even to those with some runic literacy.

So how do runes enhance a riddle? If one can determine what letter a given runic character corresponds to in the Latin alphabet, how does this knowledge illuminate the riddle and its solution? By looking carefully at Exeter Book Riddle 19 and Riddle 24, we will now explore how runes operate within a broader riddling framework.

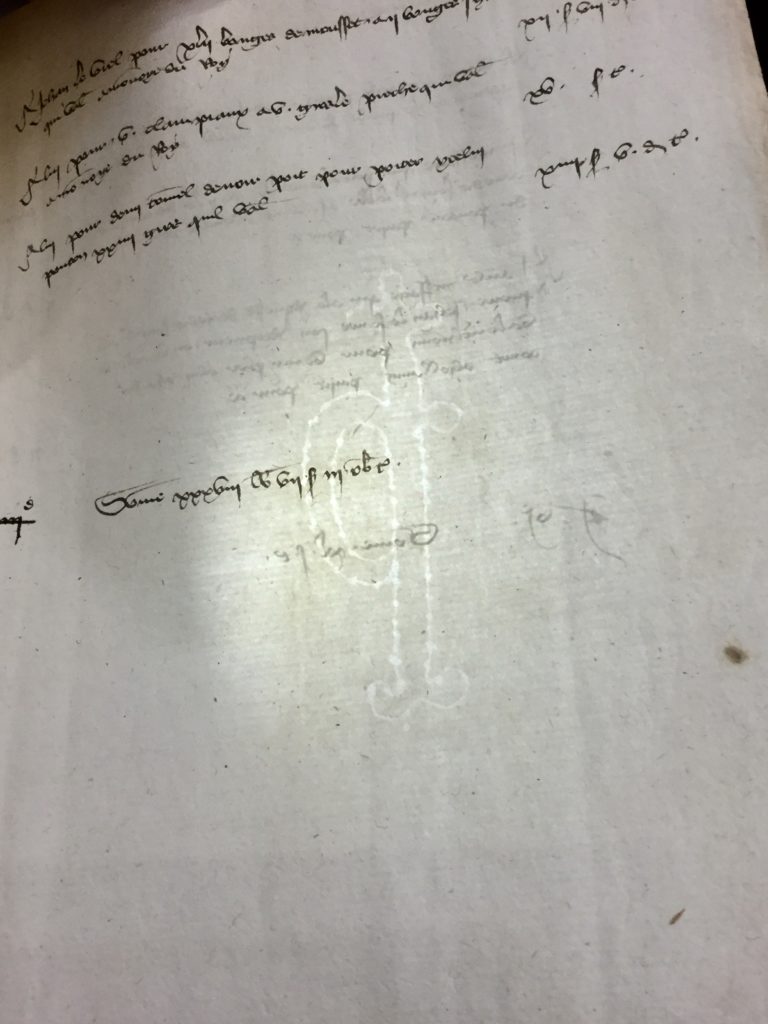

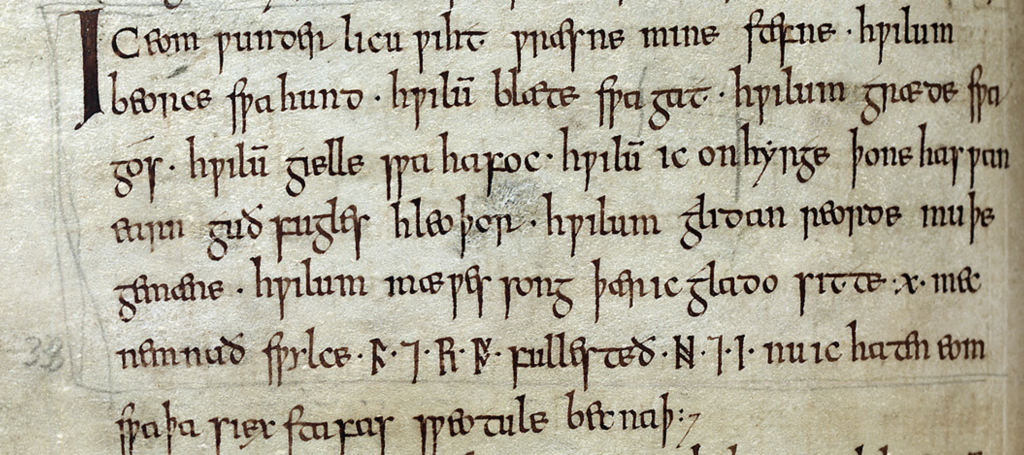

Ic eom wunderlicu wiht, wræsne mine stefne,

hwilum beorce swa hund, hwilum blæte swa gat,

hwilum græde swa gos, hwilum gielle swa hafoc,

hwilum ic onhyrge þone haswan earn,

guðfugles hleoþor, hwilum glidan reorde

muþe gemæne, hwilum mæwes song,

þær ic glado sitte. G mec nemnað,

Swylce. A ond R O fullesteð,

H ond I. Nu ic haten eom

swa þa siex stafas sweotule becnaþ.

“I am a wondrous thing—I change my voice:

sometimes I bark like a hound

sometimes I bleat like a goat,

sometimes I squawk like a goose,

sometimes I screech like a hawk,

sometimes I imitate the grey eagle,

the sound of birds of prey,

sometimes I utter with my mouth the kite’s voice,

sometimes the gull’s song,

where I gladly sit.

G names me,

also A and R.

O supports me,

H and I.

Now I am called as those six letters clearly show.”

The solution to Riddle 24 is higora, or ‘magpie’ in Old English, as the runes indicate when spelled out. In this riddle, runes function to obscure the solution from anyone unable to read these cryptic characters, but paradoxically they function also to illuminate the solution for the literate solver able to read the runes. However, as mysterious as the runes might appear to some, for those who understood them they aided in solving the puzzle.

Another riddle that uses runes is Riddle 19. In this enigma, there is a game of misdirection:

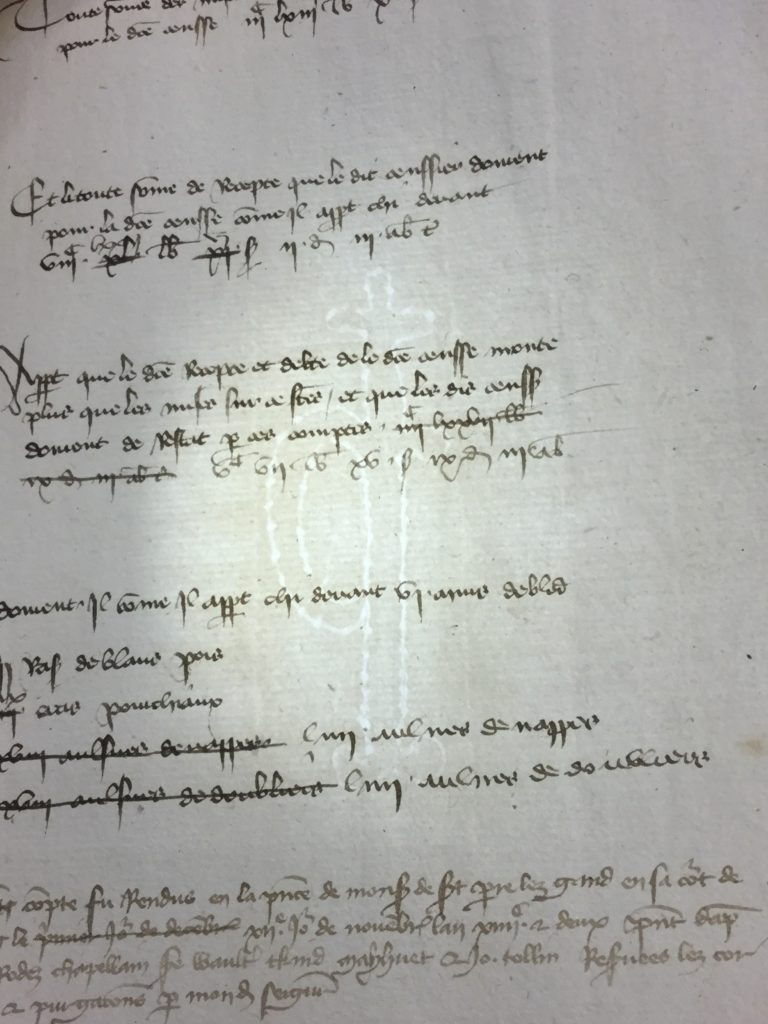

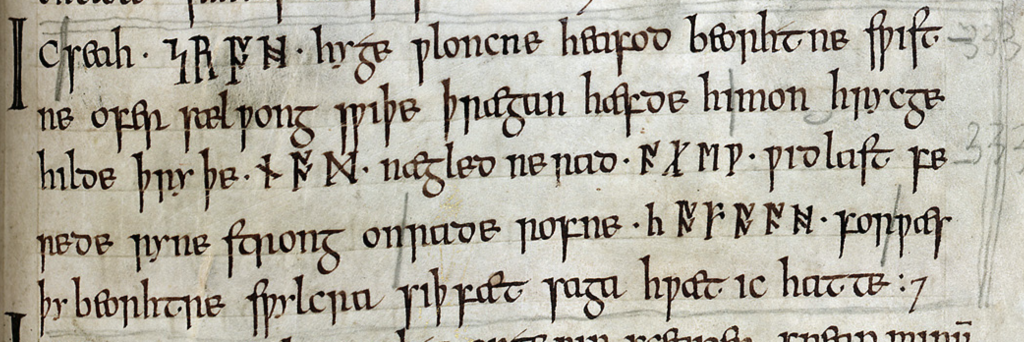

Ic seah on siþe S R O

H hygewloncne, heafodbeorhtne,

swiftne ofer sælwong swiþe þrægan.

Hæfde him on hrycge hildeþryþe

N O M nægledne rad

A G E W. Widlast ferede

rynestrong on rade rofne C O

F O A H. For wæs þy beorhtre,

swylcra siþfæt. Saga hwæt ic hatte

“I saw, on a journey,

S R O H,

proud in spirit, head-bright,

running very swiftly over the fruitful plain.

It had battle-glory on his back,

N O M,

A nailed road,

A G E W.

Traveled the far-paths,

run-strong on the road,

brave C O F O A H.

The journey was the brighter, that very expedition.

Say what I am called”

Riddle 19 contains one of the prosopopoetic riddling challenges, enigmatic formulae which conclude many in the Exeter Book collection and prompt the reader to solve the puzzle: saga hwæt ic hatte “say what I am called.”

In order to answer this enigmatic challenge, one must first understand the riddle of the runes. In this case, if one deciphers and reverses the runic characters, the letters spell out a number of Old English words that allows the solver to understand the riddle in its entirety. The runic words are decoded as follows:

S R O H = hors (horse)

N O M = mon (man)

A G E W = wega (way)

C O F O A H = haofoc (hawk)

Now the riddle becomes more comprehensible, though not totally, as the runic words create syntactic breaks in the poem:

“I saw a horse on a journey,

proud in spirit, head-bright,

running very swiftly over the fruitful plain.

It had battle-glory on his back,

a man.

A nailed road,

the way

traveled the far-paths,

run-strong on the road,

a brave hawk.

The journey was the brighter, that very expedition.

Say what I am called”

With these words semantically integrated into the riddle, some resemblance of sense is gained. The solver of Riddle 19 may now better comprehend the riddle’s meaning; however, its solution is by no means as clear for the literate rune-reader as higora is for Riddle 24. With the runes deciphered, Riddle 19 presents an image of a man riding a horse along a nailed road with a brave hawk. But this image seems to fall short of a proper solution to the riddle. Although answers have been put forth, none has proven satisfactory. Riddle 19 remains unsolved, a puzzle yet to be fully unriddled.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Further reading:

Bitterli, Dieter. Say What I am Called: The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book and the Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2009.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Spurkland, Terje. “Literacy and ‘Runacy’” in Medieval Scandinavia in Scandinavia and Europe 800-1350: Contact, Conflict and Coexistence, ed. Jonathan Adams and Katherine Holman. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2004.