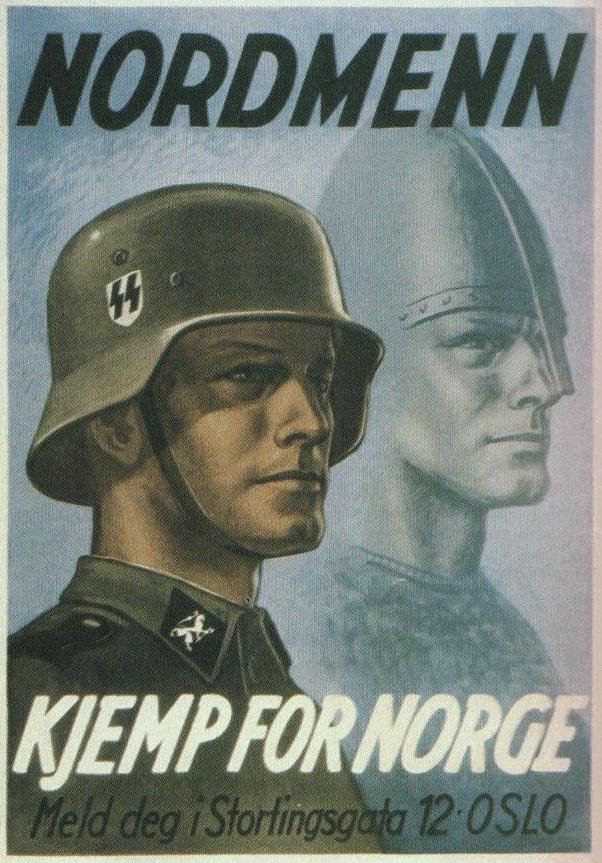

“Make Ásgarðr Great Again!”

Myth, ideology, and obscurity in troubled times

This is a story about a people who had lost their way, though they did not yet know it. They lived in fear of their neighbours, neighbours who had come to work for them, and whom they saw as primitives, troublemakers, and sexual predators. They decided to build a wall to keep them out for good – and they were damn sure that they weren’t going to be the ones to pay for it.

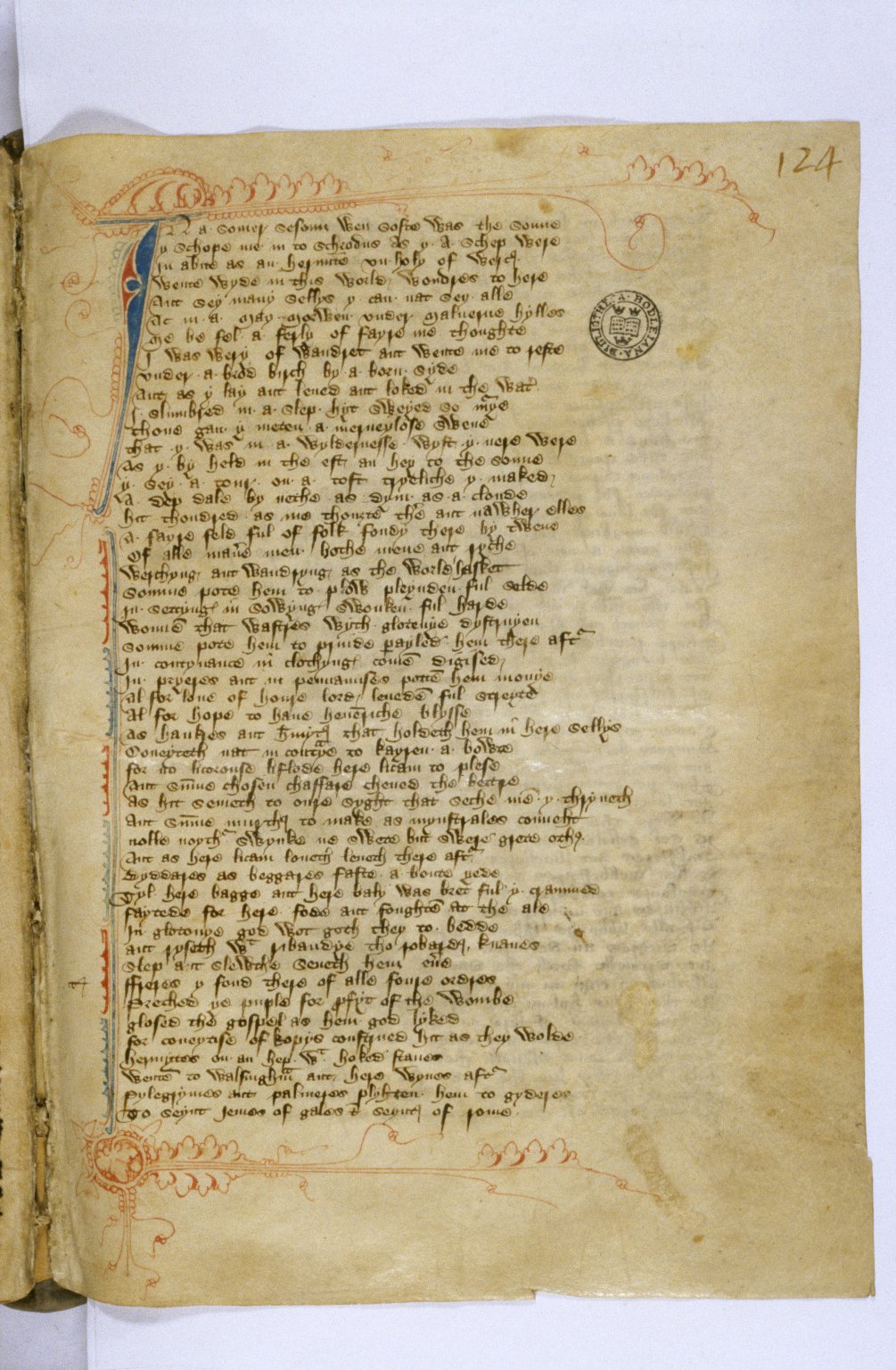

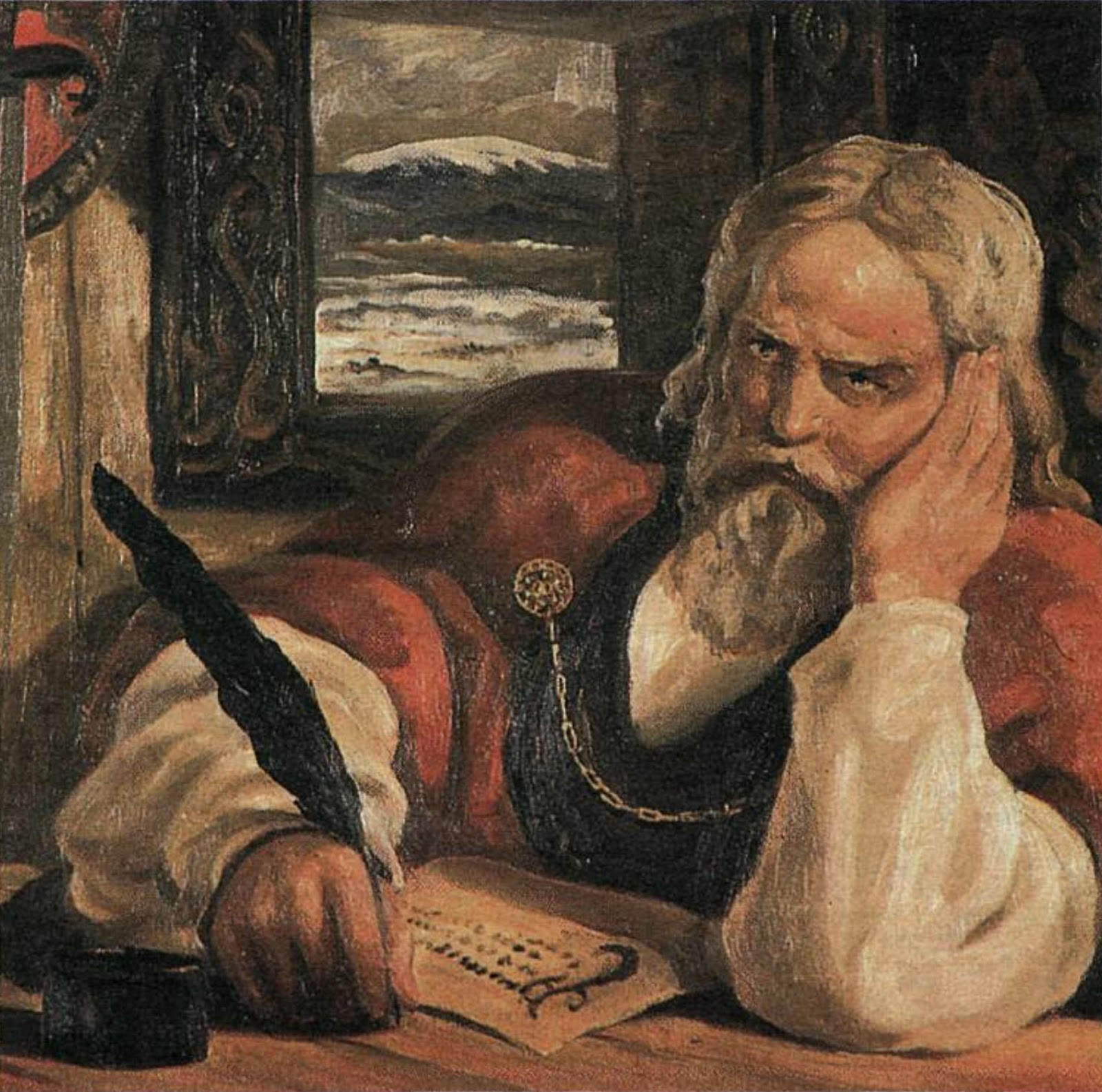

Obviously, I am talking about the Æsir, the race of gods who rule over Ásgarðr in Old Norse myth. The Icelandic author and politician, Snorri Sturluson (d. 1242) sets up the following little vignette in his Edda, an Old Norse mythological compendium written in the 1220s. Here, Óðinn is telling an anecdote:

Þat var snimma í ǫdverða bygð goðanna, þá er goðin ǫ hǫfðu sett Miðgarð ok gert Valhǫll, þá kom smiðr nokkvorr ok bauð at gera þeim borg á þrim misserum svá góða at trú ok ørugg væri fyrir bergrisum ok hrímþursum þótt þeir komi inn um Miðgarð. En hann mælir sér þat til kaups at hann skyldi eignask Freyju, ok hafa vildi hann sól ok mána. Þá gengu Æsirnir á tal ok réðu ráðum sínum, ok var þat kaup gert við smiðinn at hann skyldi eignask þat er hann mælir til ef hann fengi gert borginni á einum vetri, en hinn fyrsta sumars dag ef nokkvorr hlutr væri ógjǫrr at borginni þá skyldi hann af kaupinu … En er á leið vetrinn, þá sóttisk mjǫk borgargerðin ok var hon svá há ok sterk at eigi mátti á þat leita. En þá er þrír dagar váru til sumars þá var komit mjǫk at borghliði. Þá settusk guðin á dómstóla sína ok leituðu ráða ok spurði hverr annann hverr því hefði ráðit at gipta Freyju í Jǫtunheimum eða spilla loptinu ok himninum svá at taka þaðan sól ok tungl ok gefa jǫtnum… [1]

“It was early in the first days of the settlement of the gods, when the gods had established Miðgarðr and built Valhǫll, that a certain craftsman came and offered to build for them inside of three seasons a fortress so good that it would be reliable and safe against the Mountain Giants and the Rime Giants, even if they got into Miðgarðr. And he named his price as being that he would marry Freyja, and he also wanted to have the sun and the moon. Then the Æsir had a discussion and reached their decision, and the deal was made with the craftsman that he should have what he had named if he could get the fortress built inside of one winter, and at the first day of summer if any part of the fortress was incomplete then he would forfeit his payment … But as winter wore on, the construction of the fortress went very well, and it was so tall and strong that one could not attack it. And when there were three days until summer it was very nearly up to the fortress gates. Then the gods went to their thrones of judgement and held council, and asked each other who it was who had advised marrying Freyja off to Giantland or ruining the sky and the heavens by taking away the sun and the moon and giving it to the giants … ”

If this is the first time you have ever read a piece of Old Norse literature, you will be picking up on the theme that the Æsir do not have a very good relationship with their giant neighbours. (We should quickly note that these giants might not always have been imagined as towering “fee fi fo fum” types, they are usually depicted as simply somewhat brutish, somewhat monstrous adversarial beings).[2] According to Snorri, the civilisation of the giants precedes that of the Æsir. They emerged from the sweaty left armpit of the first anthropoid being, who was called Ymir. In the Edda, Óðinn himself says of Ymir Fyr øngan man játum vér hann guð. Hann var illr ok allir hans ættmenn[3] “In no way can we call him a god. He was evil, as are all his descendants” (though Óðinn would say that). The Æsir are descended from a different anthropoid, called Búri, who spontaneously emerged from a block of ice at some point after the awakening of Ymir. Búri then promptly set the tone for Æsir-Giant relations by killing Ymir, and using his body parts to create the world. With Ymir’s blood the Æsir made the sea, with his flesh they made the earth, his skull became the sky and his brains the clouds. Having murdered the giants’ patriarch, the gods had one last gruesome and mocking use for his corpse. Óðinn explains that:

Hon [jǫrðin] er kringlótt útan, ok þar útan um liggr hinn djúpi sjár, ok með þeiri sjávar strǫndu gáfu þeir lǫnd til bygðar jǫtna ættum. En fyrir innan á jǫrðunni gerðu þeir borg umhverfis heim fyrir ófriði jǫtna, en til þeirar borgar hǫfðu þeir brár Ymis jǫtuns, ok kǫlluðu þá borg Miðgarð.[4]

“It [the earth] is circular on the outside, on the outside lies the deep ocean, and by the shore of that ocean they [the Æsir] gave land for the settlement of the race of giants. But further inwards on the earth they made a fortification all around the world against the warlikeness of the giants, and for those fortifications they used the eyelashes of Ymir the giant, and they called the fortification Miðgarðr [Middle Earth].”

Although at first the idea of beachside property for the giants might not seem so bad, Snorri and later authors reveal that the reservations to which the giants are relegated are not really prime real estate.[5] There appear to be giants living in the place known as Muspellsheimr, which is unbearably hot, and given the association between giants and ice (e.g. the subgrouping called the hrímþursar “the Rime giants”) there may also be giants living in Niflheimr, which is forebodingly dark and cold. As John Lindow points out, the term for the giants’ homelands is usually given in the plural, Jǫtunheimar, perhaps implying that there were multiple areas of mountain and forest – places which humans did not find hospitable – where giants and trolls were thought to live in medieval Scandinavian superstition.[6] Our world, the human world, is Miðgarðr, and the realm of the gods is Ásgarðr, which in Snorri’s account is a fortification in the centre of Miðgarðr (incidentally, this prompts the question of whether humans could hypothetically just walk into Ásgarðr, or at least up to its walls, though Snorri doesn’t give us much to work with on that point). The giants are kept out with the palisades they made from Ymir’s eyelashes, with the walls they con the masterbuilder into making but never pay for, and by a dense band of forest called Járnviðr “Iron Wood”. As an aside, we might note that this is the same name of the forested peninsula which once divided Denmark from Germany, modern Danish Jernved.[7]

That is to say, a geographical feature which was viewed as a barrier to keep two warring peoples apart.

There is little doubt that the giants, as they appear in works older than Snorri’s, such as the poems of the Poetic Edda (many of which are as old as the eleventh century, if not older still), are indeed people from whom the Æsir would understandably want to be protected. But in Snorri’s telling of Old Norse myth one finds oneself sympathising with the giants, despite Óðinn’s best attempts to slander them. It was the Æsir who cast the first stone, by killing Ymir. They then claimed the good land for themselves, driving the giants into places that are too cold, too hot, too forested or too mountainous. The Æsir enjoy technological superiority over the giants, thanks to Þórr (Thor) and his mighty hammer, Mjǫllnir … er hrímþursar ok bergrisar kenna þá er hann kemr á lopt, ok er þat eigi undarligt: hann hefir lamit margan haus á feðrum eða frændum þeira[8] “… which the Rime-Giants and Mountain-Giants recognise when he holds it aloft, and that’s no strange thing: it has crushed the skulls of many of their fathers or their kinsmen”. There are occassionally giants who get the upper hand prior to Ragnarøkr (the apocalypse, Snorri’s spelling), e.g. the trickster Útgarðaloki. But usually any attempt at resistance does not stand a chance.

The relationship of the Æsir to the giants is fundamentally colonial.[9] They dominate them technologically, control their land, but they also require their labour, as we have seen in the case of the duped craftsman.[10] Moreover, the Æsir males expect to have access to giant-women, but they are consistently horrified by the thought that giant males might have access to Æsir women. When they are forced by a peace accord to let a giant-woman, Skaði, marry a male god, they trick her so that she does not pick Baldr, her preferred choice and the most attractive of the Æsir, but instead chooses Njǫrðr, who is in fact not one of the Æsir but one of the Vanir, a tribe defeated in war and assimilated by the Æsir.[11] The giants are depicted as constantly slavering over Freyja, whom the Æsir have a responsibility to protect from their advances. It is presented as uncontroversial that the male god Freyr can have sexual relations with the giantess Gerðr (by rape, according to Skírnismál in the Poetic Edda, though Snorri somewhat romanticises the congress in his Edda). Similarly, Þórr has an extra-marital liaison with a giantess named Járnsaxa. The resultant offspring, Magni, is raised as a good Áss (the singular of Æsir – stop giggling at the back). But when the male giant Fárbauti has sex with the apparently non-giant female Laufey, the resultant offspring is Loki.

Though raised amongst the Æsir, Loki is a devious figure whose own erotic encounters with the giantess Angrboða apparently re-concentrate his giant heritage, resulting in the monstrous brood of the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jǫrmungandr, and the death-deity Hel. By way of analogy, we might observe that this is a sort of thinking which is not altogether remote from colonial sexual regimes such as those of the American south. As Ida B. Wells wrote back in 1892, “the misceg[e]nation laws of the South only operate against the legitimate union of the races; they leave the white man free to seduce all the colored girls he can, but it is death to the colored man who yields to the force and advances of a similar attraction in white women” [12] (I am grateful to Jarvis McInnis for directing me to Wells’s work). I certainly do not intend to equate the actual historic suffering of real populations with the imaginary sufferings of mythical tribes. But I would propose that if we want to understand what is going on in the minds the Æsir, as Snorri depicts them, then such analogies can be tremendously illuminating.

Despite the ready interpretation that it is really the Æsir who victimise the giants, rather than the other way round, the Æsir themselves sometimes entertain the feeling that their world is in a state of decay, and that it is migrants from Giantland who are to blame for their supposed decline. Óðinn explains that:

Þar næst gerðu þeir þat at þeir lǫgðu afla ok þar til gerðu þeir hamar ok tǫng ok steðja ok þaðan af ǫll tól ǫnnur. Ok því næst smíðuðu þeir málm ok stein ok tré, ok svá gnógliga þann málm er gull heitir at ǫll búsgǫgn ok ǫll reiðigǫgn hǫfðu þeir af gulli, ok er sú ǫld kǫlluð gullaldr, áðr en spiltisk af tilkvámu kvennanna. Þær kómu ór Jǫtunheimum.[13]

“Next they did so, that they made forges and so they made hammers and tongs and anvils, and from those all other tools. And next they smithed metal and stone and wood, and so abundantly [they made] that metal which is called ‘gold’ that all their fittings and utensils were made from gold, and this age was called the Golden Age, before it was spoiled by the arrival of those women. They came from Giantland.”

Following James Barr and also Lowell Handy, who were writing about the case of Canaanite myth (a body of myth which Snorri, of course, could not have known beyond the snippets preserved in the Bible) we might call this episode a “technogony”.[14] Calling this time a gullaldr “Golden Age” is probably Snorri’s own idea, rather than a concept in Norse myth that existed in the minds of others before the 1220s. It is conceivable that gullaldr originates as a calque of Latin aetas aurea, e.g from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, although Ovid’s “Golden Age” is not so technologically advanced and more peaceful: Aurea prima sata est aetas, quae vindice nullo, / sponte sua, sine lege fidem rectumque colebat. “The first age is golden, where none commanded, / [and] of ones own accord, without law, [one] was faithful and did the right thing”.[15] But I digress.

It is worth noting that, like most “Golden Ages”, things were probably not really as good as they were supposed to be. The gullaldr might have been a time when the Æsir were wealthy, but their prosperity was founded on violence. The giant patriarch Ymir had been killed, his body used to create forifications to keep his descendants out of Miðgarðr, and all the Rime-Giants apart from one named Bergelmir and his household had been drowned by the ocean of blood that flowed out of Ymir’s corpse. (Bergelmir and his wife survived by floating on a giant wooden box, and then went on to repopulate the Giantlands, this detail presumably being drawn from Genesis’s flood narrative). Perhaps the reason Óðinn tries to convince us that this was a “Golden Age” is not because he truly believes in the glory of Ásgarðr, but because he truly believes in the nefariousness of giants. The point is not that Ásgarðr was ever that great, but rather that the giants are what is standing between Ásgarðr and greatness. It is fitting that we don’t really know who exactly the three ruinous giantesses were supposed to be. It is probable that Snorri didn’t either, and he was simply backforming from an equally cryptic verse in Vǫluspá: Teflðo í túni, teitir vóro, / var þeim vættergis vant ór gulli, / unz þriár qvómo þursa meyjar, / ámátcar mioc, ór iotunheimom. “ They played chess in their settlements, they were joyful / there was never any want for gold / until three came, maidens of the giants / very strong, from the Giantlands”.[16] By extension, Óðinn himself doesn’t really know. The leader of the Æsir knows how to propagandise in a post-truth political climate.

At the end of the world, called Ragnarǫk in the Poetic Edda and Ragnarøkr/-røkkr in Snorri’s Edda, the age-old enemies of the Æsir will finally get the upperhand. Led by Loki and the Muspellssynir “Sons of Muspell”, a force of giants will charge across the Rainbow Bridge, Bifrǫst, and vanquish the Æsir. Yet it would be a mistake to think that there is something of the Bildungsroman about this narrative, where the giants are off accumulating their forces, and finally get their revenge through their own industry. The Muspellssynir may deliver the death-blow to the Æsir, but it is actually the Æsir who undo themselves. They make a series of consistently poor decisions which leave them ill-prepared to face their foes at Ragnarøkr. Freyr trades his sword to his messenger, Skírnir, in return for Skírnir’s co-operation in threatening the giantess Gerðr into sexual relations with him. He is consequently unarmed in the final battle. Óðinn and the other Æsir refuse to kill Fenrir when they have the chance, because they do not want to defile the sacred spaces they have set up in their own honour. Óðinn himself explains that Svá mikils virðu goðin vé sín ok griðastaði at eigi vildu þau saurga þá með blóði úlfsins þótt svá segi spárnar at hann muni verða at bana Óðni[17] “The gods so highly esteem their sacred groves and places of truce that they would not defile them with the wolf’s blood, even though the prophecies might say that he would be the death of Óðinn”. This seems like a noble enough sentiment, but it must be remembered that in Snorri’s euhemerist account the Æsir are not actually divine, and are in fact much given to deception, so it would appear that there is something Óðinn is not telling us in his explanation.

Just as Fenrir ultimately destroys Óðinn, Þórr kills the serpent Jǫrmungandr but is himself killed in the process from resulting splashes of the beast’s venom: Þórr … stígr þaðan braut níu fet. Þá fellr hann dauðr til jarðar fyrir eitri því er ormrinn blæss á hann[18] “Þórr … takes nine steps away. Then he falls down dead to the earth because of the poison which the serpent spewed on him” The same tool/weapon that gave the Æsir supremacy over the giants also becomes their undoing; the story would have run rather differently if Þórr had picked up a bow, like the god Ullr. But he doesn’t. The hammer has always worked against the giants before, and so he steps into spitting range of the serpent with a blind confidence of a man who only has a hammer, and so sees only nails. Like Óðinn, Þórr too had a chance to eliminate his killer before Ragnarøkr during an attempt to catch Jǫrmungandr on a fishing line. However, Þórr took a giant with him on that expedition, one named Hymir, who quailed at the sight of the serpent and let it go. Óðinn tells the story as a vindication of the giants’ supposed cowardice and idiocy. Though I wonder if Hymir might be engaging in a spot of civil disobedience. After all, when you have spent a lifetime smashing the skulls of giants, and you then take a giant with you to help you pre-emptively kill the beast that will otherwise be your death, you can’t be all too surprised when that giant exhibits a lack of motivation in the workplace.

The Æsir are powerful and cunning, but they are not able to think ahead to the point where they will take decisions that hurt in the short term, in order to allow them to survive in the long term. As Christopher Abram observed in a paper delivered at Harvard’s “Old Norse Mythology in its Comparative Contexts” in 2013, the gods are not so different from us: when the world around them is ending, they are to be found sitting around having a conference. The refrain in the Eddic poem Vǫluspá goes: Þá gengu regin ǫll / á rǫkstóla,/ ginnheilǫg goð, / ok um þat gættuzk “The powers all went / to the thrones of fate / the divine gods / and this they discussed”. As Abram pointed out, this is exactly what humanity was doing during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in 2009. Just like modern capitalism, the Æsir have established an order that suffers from bureaucratic inertia,[19] and which is too short-sighted to prevent its own destruction. When it falls, it will take the rest of the world with it.

What is the value of drawing such analogies between the world depicted by Snorri and the world we find ourselves in today? Where Old Norse literature (the body of literature written in Iceland and to a lesser extent Norway from c. 1100 to c. 1500, to which Snorri’s Edda belongs) offers lessons for our own time, those lessons should be told. Of course, they will have absolutely no impact whatsoever. No politician is going to read this, buzz their secretary, and exclaim: “Pat, get in here! I’ve just found out about this thirteenth-century Icelander called Snorri Sturluson and I’ve totally rethought my policy on fracking!”. So the need for the past to teach the present is not why I offer these analogies (even if it is a strong second place). Rather, I would propose the value of the opposite possibility: that we can sometimes permit the present to teach the past. Naturally, we have to be very wary of anachronism in doing so. Medieval people did not think of things such as the environment or race in the way that we do today. Many of the key concepts around which our world is built cannot even be expressed in the vocabulary of medieval languages. But medieval people often did possess the psychological building blocks which would later go into constituting those ideas as we know them.

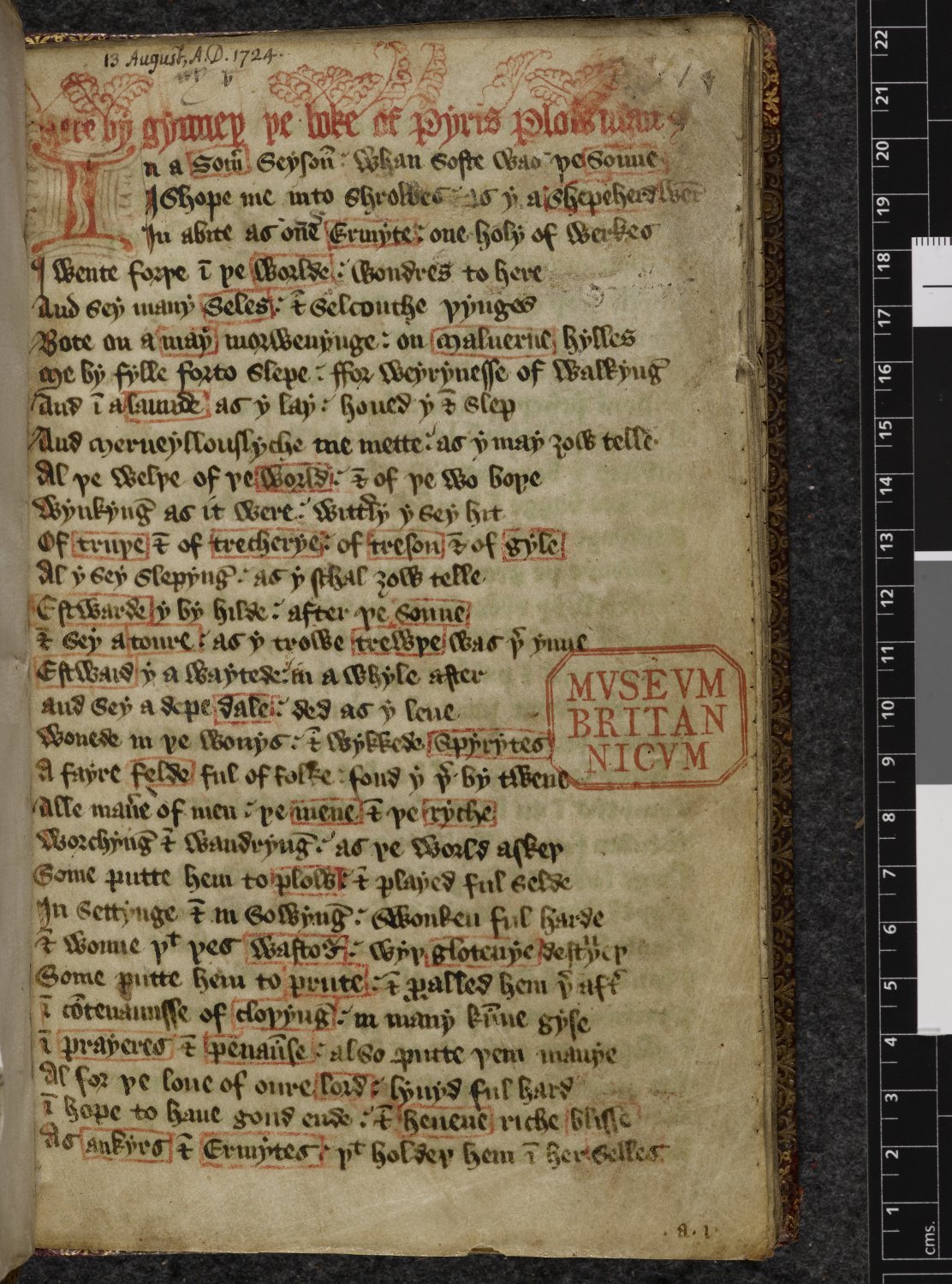

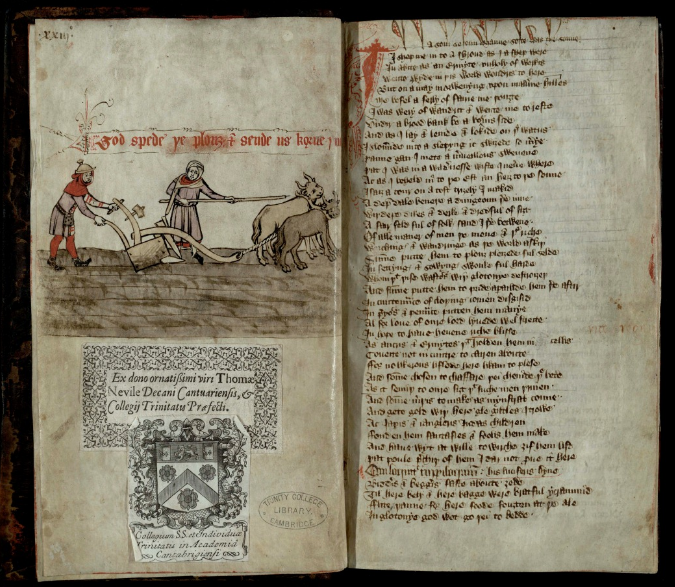

To my mind, the chief problem attendant to understanding Snorri’s Edda is also the chief intellectual opportunity: Snorri was more like J. R. R. Tolkien than he was like David Attenborough. His aim was not to describe and document. He was not attempting to present a rigorous, scientifically accurate account of the myths and religious traditions of his forefathers. Rather, he was cobbling together an imaginative fictional world, wonderfully eclectic in its use of sources. Snorri would borrow anything from anyone. His Edda is a composition of pre-Christian Norse poetry, folk superstitions, Latin learning, Biblical apocrypha, and a fair few generous dollops of Snorri’s own creativity. The result is one of the most enigmatic and exciting works of world literature. Snorri’s eclecticism is beautiful, but it also makes it very hard to know precisely what we are discussing when we attempt to analyse a portion of his mythological world. What bits are “authentically” pre-Christian? What bits are the intellectual achievements of the thirteenth century? Much ink has been spilled on sorting Snorri’s sources accordingly, some of the weaker smudges my own.

The principle value of the type of analogy I have suggested here is the insight it can give us into Snorri’s own thinking – and the thinking of his fictional characters. If we wanted to provide an account of the ideology of the Æsir (let’s call it “Æsirism”) how would we go about it? One way would be to attempt to pick out the bits that could be from the Viking Age, via juxtaposition with sources older than Snorri, e.g. Eddic poetry, archaeology, accounts by Adam of Bremen (fl. 1070s) and Ibn Fadlan (fl. 920s) etc. Afterwards, we could also integrate Snorri’s Edda with what we know about political thought from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, as per Sverre Bagge’s work on another thirteenth-century masterpiece, Konungs skuggjsá.[20] This would be a very worthy and enlightening project. But it would not give us a picture of Æsirism as a unified ideology. True, ideologies are always conditioned by time and place – the capitalism of seventeenth century Holland is different to the capitalism of present day Florida, the feminism of Shulamith Firestone is different to that of Sandi Toksvig – but ideologies are at their core timeless. They exist immaterially as a set of ideas, beliefs about the world, about how it works and how it could be made more just. The pre-occupations of our own world provide a useful diagnostic for exposing those beliefs, in everything from works of literature to Kinder Surprise Eggs (or so Slavoj Žižek would have us believe, anyway: http://bit.ly/2htZ8Cc). So what do Snorri’s Æsir think about the notion we now call race? About the legitimacy of power? About bureaucracy? About sex, war, and natural resources? Yes, all these questions are impositions from our own troubled times. But so long as we recognise that, and we recognise the limits of our questioning, a pinch of anachronism paradoxically allows Snorri’s Edda to exist in its own right as a rich imaginative world of subcreation much like Tolkien’s Middle-earth. We can interview the Æsir, appreciating Æsirism as Snorri’s own invention rather than as a distorted memory of the Viking Age.

In this way, being worried for the fate of the world might just make us better scholars, as we incline our ears more closely to our source texts, listening more intently for the ghosts that prefigure the monsters of our modern situation. One might protest that it is ridiculous to be pursuing Old Norse philology – an almost comically obscure topic – at a time when, like the Æsir, we face the prospect of seemingly apocalyptic ecological and political crisis. Perhaps that’s true. There may well be something Æsirist in today’s ethno-nationalist inflected capitalism, but in this regard there is also something Æsirist about those of us who would resist it, too. As the sun turns black and the earth sinks beneath the waves, we know we cannot win. We go to meet our enemies with tools that will do nothing, but which we love too much to relinquish.

Richard Cole is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He has taught Old Norse at Harvard University, University College London, and Århus Universitet. He has published on Old Norse philology in Saga-Book, Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, Scandinavian Studies, and other journals. This blog post is a side-project from an article currently under preparation, provisionally entitled: “’Make Ásgarðr Great Again’, or, is there an Æsir-ist ideology?” Correspondence can be directed to: richardcole@alumni.harvard.edu.

[1] Snorri Sturluson. Edda. Prologue and Gylfaginning. (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1988) p. 34 [ch. 42]

[2] Eyvind Fjeld Halvorsen & Anna Birgitta Rooth. “Jotner” in Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder. Vol. 7. Ed. by Allan Karker. (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde og Bagger, 1962) pp. 693-700.

[3] Gylfaginning, p. 10. [ch. 5]

[4] Gylfaginning, p. 12. [ch. 8]

[5] Rudolf Simek. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Trans. by Angela Hall. (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1993) p. 180.

[6] John Lindow. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) p. 206.

[7] To my knowledge, the first to point out the similarity between mythical Járnviðr and historical jernved was: Gustav Klemming. “Jernveden” in Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon. Vol. 13. Ed. by Chr. Blangstrup. (Copenhagen: J. H. Schultz Forlagsboghandel, 1922) p. 52. The concept comes under stimulating theoretical discussion in an unlikely place, namely: Frederick Engels. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. (New York: International Publishers, 2011 [1891]) pp. 153-154. For further comments on Old Norse myth by Engels, including his apparent familiarity with Sophus Bugge and Anton Christian Bang, see also: p. 102, pp. 147-148, 196-199. In a letter to Laura Lafargue (née Marx) written on the 23rd November 1884, Engels also writes that: “[William] Morris … was here the other night and quite delighted to find the Old Norse Edda on my table — he is an Icelandic enthusiast — Morris read a piece of his poetry (a “refonte” of the eddaic Helreid Brynhildar (the description of Brynhild burning herself with Sigurd’s corpse) … their art seems to be rather better than their literature and their poetry better than their prose”. http://bit.ly/2hhBTL6 (Last accessed, 11th December 2016).

[8] Gylfaginning, p. 23. [ch. 21]

[9] Indeed, it has been suggested that Skaði, with her skis and hunting prowess, is supposed to be a Finnic figure, representing the indigeneous pre-Germanic-speaking population of Scandinavia. Her husband. Njǫrðr, on the other hand, prefers to live in the coastal regions, of the sort where the majority of Norway’s Germanic-speaking population lived during the Middle Ages. See: Lois Bragg. Oedipus borealis. The Aberrant Body in Old Icelandic Myth and Saga. (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004) pp. 85-86.

[10] One might also cite the example of Gefjun’s giantish bulls, or Þórr taking Hymir on his fishing expedition.

[11] Historically the war between the Æsir and the Vanir has also been viewed as a memory of some long-lost, actual religious conflict. On this view, now outdated, see: E. O. G. Turville-Petre. Myth and Religion of the North. The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964) esp. pp. 156-162.

[12] Ida B. Wells. Southern Horrors and Other Writings. The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells. Ed. by Jacqueline Jones Royster. (Boston: Bedford Books, 1997 [1892-1900]) pp. 53-54.

[13] Gylfaginning, p. 15. [ch. 14]

[14] James Barr. “Philo of Byblos and His ‘Phoenician History’”, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 57 (1974) pp. 17-68. Lowell K. Handy. Among the Host of Heaven. The Syro-Palestinian Pantheon as Bureaucracy. (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994) pp. 136-139.

[15] Ovid. Metamorphoses. Vol. 1. Ed. & trans. by Frank Justus Miller. Rev. by G. P. Goold. LCL 42. (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1916) p. 8. [Bk 1: 89-90] My translation used.

[16] Edda. Die Lieder des Codex Regius nebst verwandten Denkmälern. Ed. by Gustav Neckel & Hans Kuhn. (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1983) p. 2. [stz. 8]

[17] Gylfaginning, p. 29. [ch. 34]

[18] Gylfaginning, p. 50. [ch. 51]

[19] Concerning the canard that capitalism is the antithesis of bureaucracy, think of the last time you attempted to get an Xfinity internet connection set up, or changed your address with your bank, or tried to re-arrange a delivery with a courier service. The “love affair” of capitalism with bureaucracy is treated by: David Graeber. The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. (New York: Melville House, 2015). In fact, it ought to be protested that the political culture of the Æsir is not wholly bureaucratic – indeed, in many ways it is anti-bureaucratic because it exhibits virtually no trace of alienation in a Marxian sense. However, these are arguments for another time.

[20] Sverre Bagge. The Political Thought of The King’s mirror. (Odense: Odense University Press, 1987).