The latest in the Chequered Board‘s ongoing series of poetic translations is one of the most famous, and most haunting, poems in Old English literature.

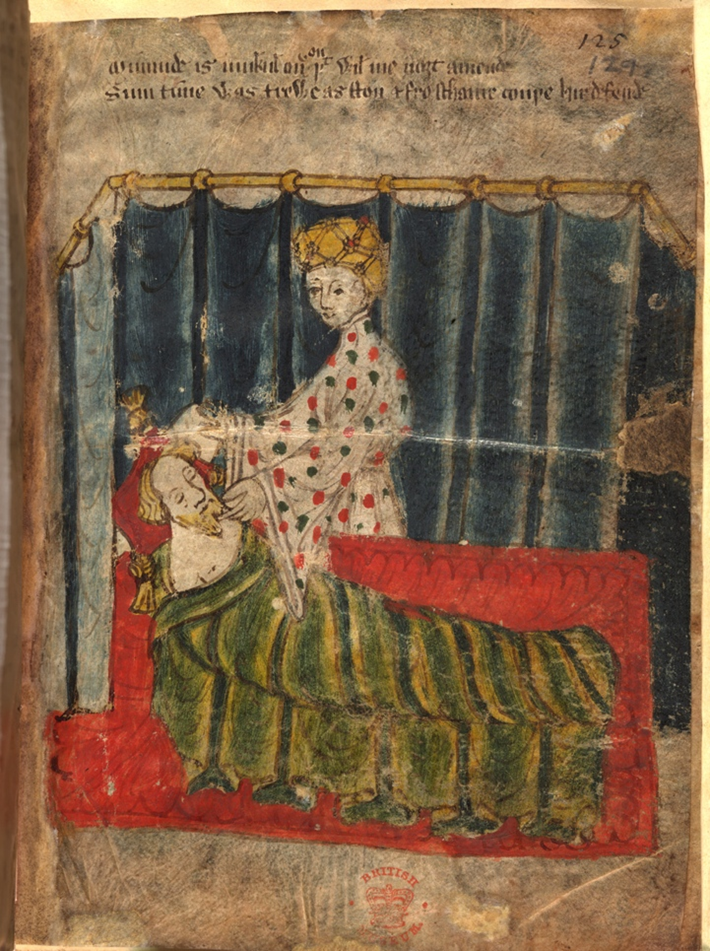

The Wanderer, contained in the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501), is one of a group of nine Old English poems known as the elegies, poems characterized by “a contrasting pattern of loss and consolation, ostensibly based on a specific personal experience or observation, and expressing an attitude towards that experience.”1 In The Wanderer, a litany of loss which extends throughout nearly the entirety of the poem comes to an abrupt halt in its final lines. These concluding moments assure the reader that it shall go well for those who seek consolation with the “father in heaven,” returning to the opening lines of the poem in which we are confronted with a lone traveler seeking to find some kind of favor or honor with his maker. The poem seems to give us resolution, though not one to be enjoyed in the present.

Early in college, long before I had remotely considered the idea of becoming an Anglo-Saxonist, I gave my heart to a very different poem, T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. I loved the poem’s frustration with futility, its questions left unanswered, and its dips into existential crisis. The poem impressed me with its lament for the mundaneness of life and concern with ever-passing time: “I shall grow old… I grow old… / I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled” (ll. 120-121). The speaker of The Love Song is keenly aware of his status and absurdity – “I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker” (l. 84), “Almost, at times, the Fool” (l. 118) – and also of the difficulty of conveying meaning in the modern world – “That is not it at all, / That is not what I meant, at all” (ll. 109-110). The poem leaves us in the dreamscape of mermaids singing on the sea, “and we drown” (l. 131). It is not a happy poem.

Strangely, The Wanderer, written perhaps a thousand years before Eliot penned his Love Song, strikes some of these same chords. The poem begins with the image of a lone traveler with calloused hands, wandering over the seas and on land with a burdened mind. While Prufrock fears the future, the speaker of The Wanderer grieves for a past in which he enjoyed the company of kinsmen and the secure status of servitude to a lord. Images of a golden past, along with the faces of friends, “float” away from the speaker, and he reflects upon the death of all things of this world, offering a rather ordered catalogue of unfortunate events produced by a failing world. To say the least, it is not a happy poem. But it is extremely powerful poetry responding to the same concerns with which modern poets wrestle. Its world of mead-halls and thanes and warrior-glory is inexplicably also our world of suffering and futility and stagnation.

My main goal in offering this translation is to do some measure of justice to the beauty and depth of the original. I have stayed as close to the original language as possible, hopefully creating a work which sounds poetic to the modern ear while retaining some of its strangeness. C.S. Lewis famously wrote of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring: “here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.”2 Whether or not one believes these words are true of The Lord of the Rings, I hope you will agree that they are true of The Wanderer. The world of The Wanderer may be grey and rimmed with frost, but it is also a world of exquisite beauty, a world where the grief of the human soul is laid bare – the soul fully exposed in all of its wretchedness, yet not wholly defeated.

Maj-Britt Frenze

PhD Student

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

1 S.B. Greenfield, “Old English Elegies,” in Continuations and Beginning: Studies in Old English Literature, ed. Eric Gerald Stanely (London: Nelson, 1996), 143.

2 C.S. Lewis, in Time and Tide, August 14, 1954, and October 22, 1955. Reprinted in Lesley Walmsley, ed., C.S. Lewis: Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces (London: HarperCollins, 2000).