In my recent blog discussing a new form of theatrical medievalism in which I have become immersed—allowing me both a creative and intellectual outlet—I centered my discussion on my creative direction and process and how my studies in medieval literature informed my directive style at two local Renaissance Faires in North Central Massachusetts which I was involved with managing, organizing and directing, Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire at the Community Park in Winchendon, MA and Enchanted Orchard Renaissance Faire at Red Apple Farm in Phillipston, MA. Wyndonshire, the first of these faires, will be the center of my discussion today as I explore the way this project engaged local performers, vendors and community members who came together to cocreate an event that revitalized the town and region. It was also a lot of fun, especially when it all came together on the final weekend in April last year.

Wyndonshire began with an idea proposed by Parks and Recreation Member Dawn Higgins, who championed the initiative and served as RenFaire Coordinator this past year, helping coordinate costume clinics for character actors with Costume Coordinator, Ashley Rust, and vendors with then Park and Recreation Coordinator, Tiffany Newton. My wife, Rajuli Fahey, and I joined on as community members and part of the Planning Group for Winchendon’s RenFaire initiative, but came to wear many hats and serve in numerous roles, including as Creative, Theatrical and Entertainment Directors. Well before directing and academic consulting, I began with world-building a fantasy kingdom, drawing inspiration from town history, and applying my knowledge of medieval culture and lore to imbue the scripts I created as Wyndonshire Playwright. I drew also from my studies and love of medievalism in considering the audience and to both appeal to and surprise patrons. And, as mentioned in my previous blog, I modeled my approach in part on the aesthetic of wonder operative in many of my favorite works of medieval literature.

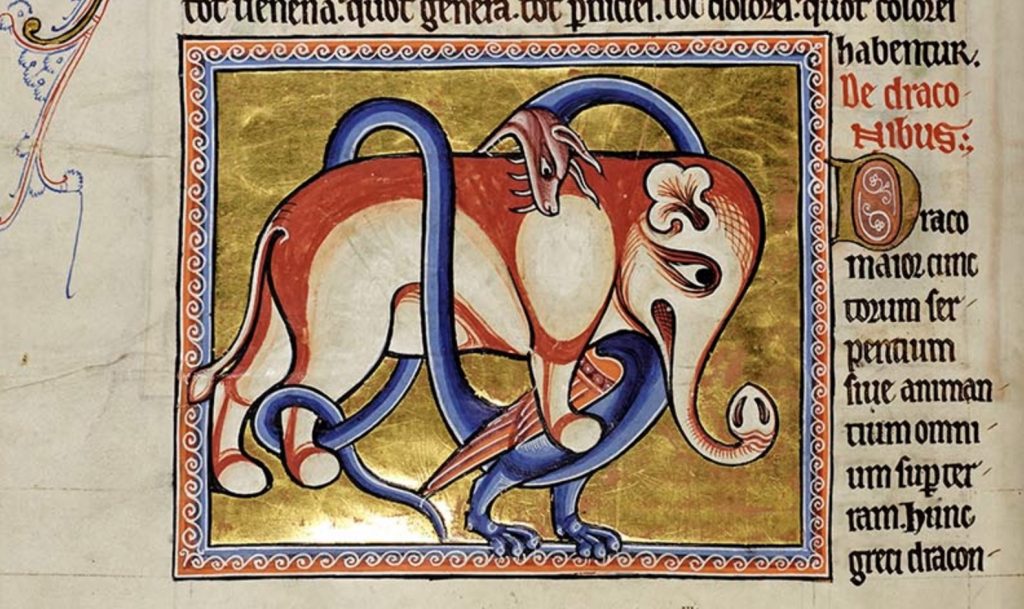

Creating the characters was a blast. I conceived of three main houses, and three primary nobles vying for power: the Blue King (James Higgins), the Green Queen (Tammy Dykstra), and the Red Baron (Dave Fournier). Rajuli created the graphic art for Wyndonshire, and she suggested noble family’s crest included a local animal as a sigil, so we chose the stag for the king, the otter for the queen and the fox for the baron. I also created a host of characters to populate the kingdom: townsfolk, rogues, pirates, vikings, knights, ministers, and additional nobility. There are also wondrous creatures from literature, myth and legend: fairies, merfolk, witches and sirens. Of course, this conglomerate of fictitious characters borrows from medieval and modern traditions, and reaches into the realm of the imaginary. Wyndonshire can only be described as a historical and literary anachronism and amalgamation. In this way, this faire is full fantasy, designed to appeal broadly to audiences interested in premodern and early modern times or their perception of those earlier historical periods. In other words, designed to meet the expectations of those who would typically attend a modern Renaissance Faire.

It was at this point that magic truly began happening, and it came from the local community. At our auditions, the synergy was palpable—dozens of folks came out to try and embody one of my characters or contribute their creative touch to this growing community project. There were people from different backgrounds coming together to cocreate immersive theater—some folks were part of community theater productions, others were veteran “Rennies” and even Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying groups got involved. Everyone rose up and became a creative team. One example of many was the work of Tammy Dykstra, who was cast as the Green Queen, and later stepped into the role of Music Director, taking on a group of singers, with a spectrum of training and experience. Assisted by Planning Group member, Jacque Ellis, Tammy and the Wyndonshire Singers produced a masterful “pub sing” that was engaging for both spectators and participants, and provided some ribaldry, entertainment and comic relief against a plot that was otherwise often grim and tragic.

Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire also featured a Belly Dance showcase that paid homage to the evolution of American Belly Dance and American Renaissance Faires, organized through partnership between Rajuli, Rachel Moirae of Our Dance Space, and Cheryl Kalilia of PsyBEL. The showcase featured regional dancers with a variety of styles—some improvisational, some choreographed—all performing to music with live percussion accompaniment added by spectating dancers, performers and patrons, which highlighted the collaborative and community spirit of the faire. From there, Wyndonshire spiraled outward, as performers and vendors were reaching out looking to get involved in the expanding project.

Numerous performance, historical reenactment, theatrical and musical groups donated services, sometimes for free and more often at discounted rates, to help get this event off the ground since initial funding was limited and in large part came from Massachusetts Cultural Council grants. Everyone pitched in to make the event possible, including The Knights of Lord Talbot, Meraki Caravan, The Phoenix Swords, The Shank Painters, The Harlot Queens, The Warlock Wondershow, The Misfits of Avalon, Dead Gods are the New Gods, The Green Sash, The Mt. Wichusett Witches, and solo performers, such as stilts walker, LaLoopna Hoops, and fire dancer, Noodle Doodle.

Signage was of course an essential element of the faire as well, both because signs add to the atmosphere and create the physical space, and because they helpfully direct patrons where to go. Another community member, Micayla Sullivan, who also played the Robber Baroness, took the lead on this and other crucial aspect of stagecraft as our “Sign Smith” along with a handful of other character actors. All the raw wood for the signs was donated from a local lumber company, Killay Timber Company in Royalston, MA, which made the production of Wyndonshire signage possible even without a budget. Similarly, local company, French Family Foundation in Winchendon, MA, donated lumber from local hardware store, Belletetes, to create the Wyndonshire gate, which James Higgins (who played the Blue King) and Dawn Higgins constructed for the event. Furthermore, local recording studio Blu3Kat Records volunteered to support the event’s sound management, and members from the local artist collective, Eldwood Council (especially Jacob Bohlen and Tom Fahey), partnered with FaeGuild Wonders, in order to create and build second main stage, the Mirage Stage, at Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire.

As performers and vendors were signing up to be part of the Wyndonshire, characters deepened and developed alongside and in tandem with my scripting. The first act of this faire, which will run one more year (June 21-22, 2025), involves conflict between the Blue King and the Green Queen for sway over the realm of Wyndonshire, with the Red Baron biding his time and waiting for any opportunity to climb into greater power. To avoid open war, in an attempt at “peace-weaving” if you will, the Blue King offers his daughter’s hand in marriage to the Green Queen’s son, thereby uniting the realm and settling the question of authority. Of course, each noble is still plotting their opponent’s’ demise, as the game of thrones continues subversively, and breaks out at the wedding feast, resulting in usurpation and regicide.

In order to achieve the action scene in a manner that was safe and professional, we called upon the expertise of Frank Walker (Green Champion) who embraced the role of Combat Coordinator and worked out the staged combat with his historical reenactment group, The Knights of Lord Talbot, and in particular David Geary (Blue Champion) and Cameron Hardy (Red Champion), who were also performing combat demonstrations and facilitating a tournament of champions with historical weaponry and armor earlier in the day. Needless to say, this dramatically enhanced the plot and overall theatrical delivery of the climactic scene, and highlights how it was not just the cast of character actors but also performing groups who were collaborating to produce the drama of the Wyndonshire Wedding.

Some performing groups contained some scripted character actors that were part of the core cast. For example, the Mt. Wichusetts Witches came to Wyndonshire and set the stage for the carnage, and instrumental in twisting fate and turning the wheel of fortune. They contributed to the physical space by creating the Witches’ Den on the borders of the Faywood, where desperate Wyndonshire nobility come to make illicit pacts in service of their respective aims. The Mt. Wichusetts Witches, especially Wyndonshire’s Weird Sisters (Kate Saab, Chrissy Brady and Siobhan Doherty), who engaged in multiple immersive skits where they made magical bargains with representatives of the noble houses, culminating in a flash mob spell at the royal wedding that allowed the Green Prince (Drew Dias) to escape with the Fairy Prince (Sasha Khetarpal-Vasser) and the Blue Princess (Melanie “Melegie” Lemony) with the Siren (Jessa Funa), before smoke clears and the subsequent chaos erupts.

But the regicide was not the end of the action. After the Green Queen seems to have consolidated power and claims unilateral victory, there is another surprise in store: a peasants revolt instigated by a rogue rebellion, overlooked by the Sheriff of Shirewood (Jennifer MacLean) and led by the Robber Baroness (Micayla Sullivan) with the Hooded Rogue (Mitch Lang), Masked Bandit (Mandaline Blake), the Pirate Queen (Katharine Taylor) with her Pirate Quartermaster [Jarod Tavares] and the Green Sash, led by Viking Jarl (Jason Sumrall) with his Berserker (Andrew Hamel), Shieldmaidens (Sylvia Sandridge, Sara Hulseberg, Ashley Sumrall & Gabrielle Emond) and Thanes (Gary Joiner, Daniel Berry, Jeffery Allen Evans, Matthew LeBlanc, Henry Peihong Tsai, Gavin Leo, Richard Sprusanky, Joshua Coffin, et al.).

Indeed, The Green Sash, a “live history” and historical reenactment group (organized by Jason Sumrall) built and became our Viking settlement at the RenFaire. This group not only helped build the world of Wyndonshire, but like The Knights of Lord Talbot and Mt. Wichusetts Witches, The Green Sash became an integral part of the plot and interwoven into the story, contributing numerous immersive theatrical skits throughout the event, including singing and raiding Wyndonshire Town with the Wizard, conspiring with rogues and pirates to overthrow the nobility, and ultimately aiding the people’s revolution at the conclusion of the faire.

Another interwoven subplot at Wyndonshire involved the misadventures of the Fairy Court in the Faywood, which was primarily organized by Amy Boscho in partnership with Emilie Davis and many others. Amy is a local business owner and community member who was also part of the Planning Group for the faire, and she both directed the immersive theatrics surrounding the Fairy Court and coordinated the vendors at the Fay Marketplace in the Fairy Grove near Wyndonshire Gate. Moreover, to further develop the mythic elements near Faywood, professional mermaids, led by Tolkien scholar, Shae Rossi, adorned the shore of the nearby pond at the Winchendon Community Park.

By the end of the process, almost every character was cocreating at some level with the actor playing them, and in one case, one of the character actors, Jessa Funa, (who played the Siren character) even collaborated with me on an immersive subplot centered on fairy romance between herself and the Blue Princess. The sheer extent of community contributions to this event was truly incredible and has inspired me to interlace the storyline of Wyndonshire with its sister faire, so the two plots will interact and events at Wyndonshire will ultimately affect the fate of Enchanted Orchard. A project of this scope and magnitude takes a team—a village—and I am honored to be part of such a collaborative community, now FaeGuild Wonders, which was inspired to participate in a this exciting form of public medievalism.

Additionally, Park and Recreation Chair, Deb Bradley stepped up when the faire needed a liaison, and served as a stage manager during the event, a second representative from the Winchendon Park and Recreation Commission who played a critical role in the planning and operations of the faire. And, Red Apple Farm partnered in advertising the event and as one of the major food vendor, providing standard RenFaire snacks and specialty cider imported from the neighboring agrarian realm of Enchanted Orchard.

Although Wyndonshire did not return for 2025, I am optimistic that it will have a triumphant return in 2026.

Richard Fahey

Ph.D. in English

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Creative, Entertainment & Theatrical Director

Playwright & Academic Consultant

Wyndonshire Renaissance Faire (2024)