After almost forty-years without a major motion picture adaption, David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021) was much anticipated and made quite a splash, but pulled mixed reviews from scholars and critics.

The film’s primary source material, the medieval alliterative poem Gawain and the Green Knight, happens to be my personal favorite work in Middle English, my favorite Arthurian romance and my second favorite work of medieval literature following only Beowulf. Indeed, because I find both the story and poetics so fascinating, my very first blog explored possible functions of the bob and wheel in Gawain and the Green Knight. I have always read the poem as a tale of a hero brought low and the three conclusions offered by the Green Knight, Gawain himself and King Arthur’s court provide a variety of interpretations from recognition of the hero’s humanity to his feelings of failure and shame to the merriment and celebration of his chivalry by king and court.

The poem’s concatenation on themes (such as schame “shame” emphasized in the “bob and wheel” structure) drives these points home but also mimics the psychological experience of anxiety and a nagging, internal monologue. The mystery of the enigmatic Green Knight haunts the entire tale. The parallelism, especially between Gawain and the Green Knight, as well as the playful emphasis on games, exchanges and hunts produces a thrilling, at times dizzying, narrative that is rich with implication and subterfuge.

Often with modern film adaptions of medieval literature, directors and producers make what I consider to be a fatal mistake of perceiving virtually every medieval tale as an action movie. In my view, this fundamental bias plagues every film adaption of the poem to date, and when I learned Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021) was under production and forthcoming, I will admit I was rather skeptical. However, even from the trailer, it seemed—at least to me—this adaption of the medieval poem might get some things right which previous film adaptions like Stephen Weeks’s Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984) staring the late Sean Connery as the Green Knight did not seem to pick up on. When The Green Knight was released in theaters, I went to see it, making it the only film I have seen in a movie theater since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thankfully, it did not disappoint.

Many other medievalists and film critics have reviewed this much-anticipated film, some wishing there was more of an action movie component, others criticizing the Mallory-esque titling and expanded episodes in the film, and still others praising the film’s orientation as a “coming of age” tale, its attention to detail and how film makes themes such as Gawain’s shame and chivalry intriguing to modern audiences. Personally, I loved it.

There were some odd decisions which I did not quite understand such as the introduction of a talking fox (a feature of medieval beast fables, but appearing nowhere in the film’s Middle English source). Similarly, demoting Gawain from the status of knight made little sense to me and rather than as an egoistic knight demonstrating hubris, Gawain appears as a desperate and neglected aspirer doomed to a life of psychological trauma. The humanization of Gawain was apparent throughout, and Dev Patel gives a stunning performance in his role as Gawain, but the arch of his character is somewhat flattened due to these changes in Gawain’s status and characterization. Still, overall, this movie hits the nail on the head for me.

In particular, the Green Knight is in full green man form and spot on. The story is presented not as an action movie but as a psychological thriller. Emphasis on games, exchanges and hunts is imbedded throughout the movie. The visual components from cinematography to mise-en-scène are eye-popping as the film frequently displays surreal imagery to create a psychedelic mysticism associated with the Green Knight as well as Morgan Le Fay and Gawain’s quest as a whole. Additionally King Arthur and Queen Guinevere are shown as diminished in their old age, and this generates a sort of magical realism within the film.

For some, the movie will perhaps be too vulgar or too artsy-fartsy. Others, expecting to watch Gawain’s epic battles, may likewise be disappointed. Nevertheless, I agree with reviewers who observe a notable affinity between the medieval source and this modern rendition. In my opinion, Lowery’s The Green Knight represents a modern film adaption like few others: one that has its finger on the pulse of the medieval poem which inspired its creation.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Digital Text

Gawain and the Green Knight. Middle English Compendium: Middle English Poetic Corpus (2/2/2019).

Modern English Translation

Deane, Paul. Sir Gawain & the Green Knight. Alliteration.net: The Pearl Poet (1999).

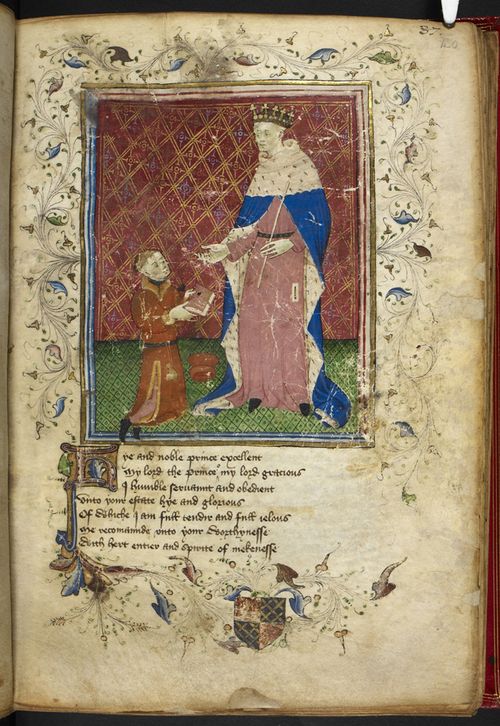

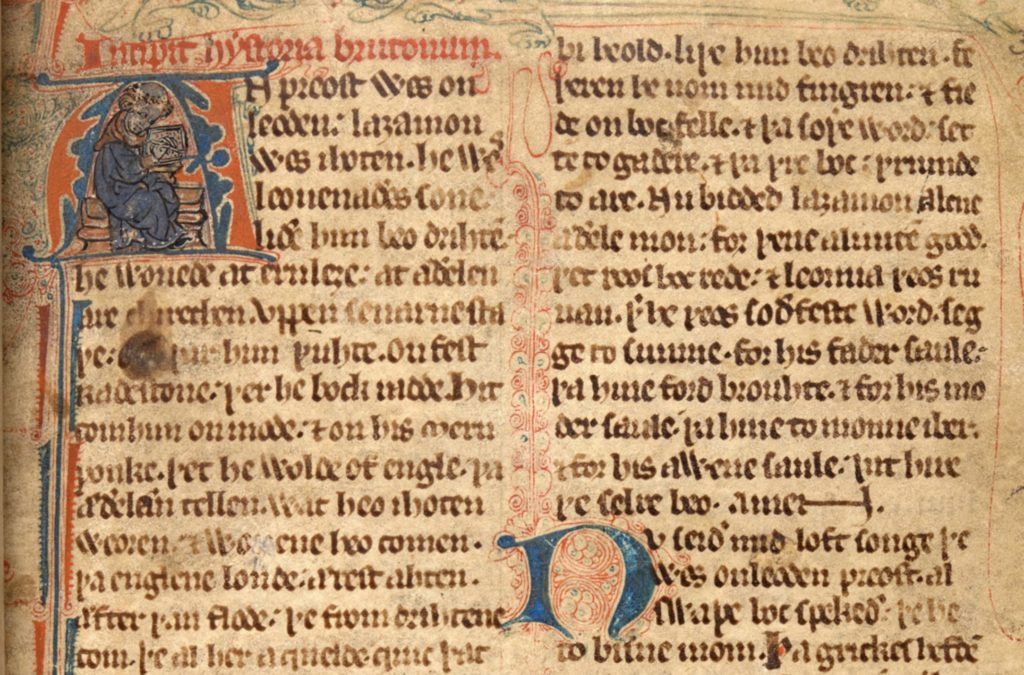

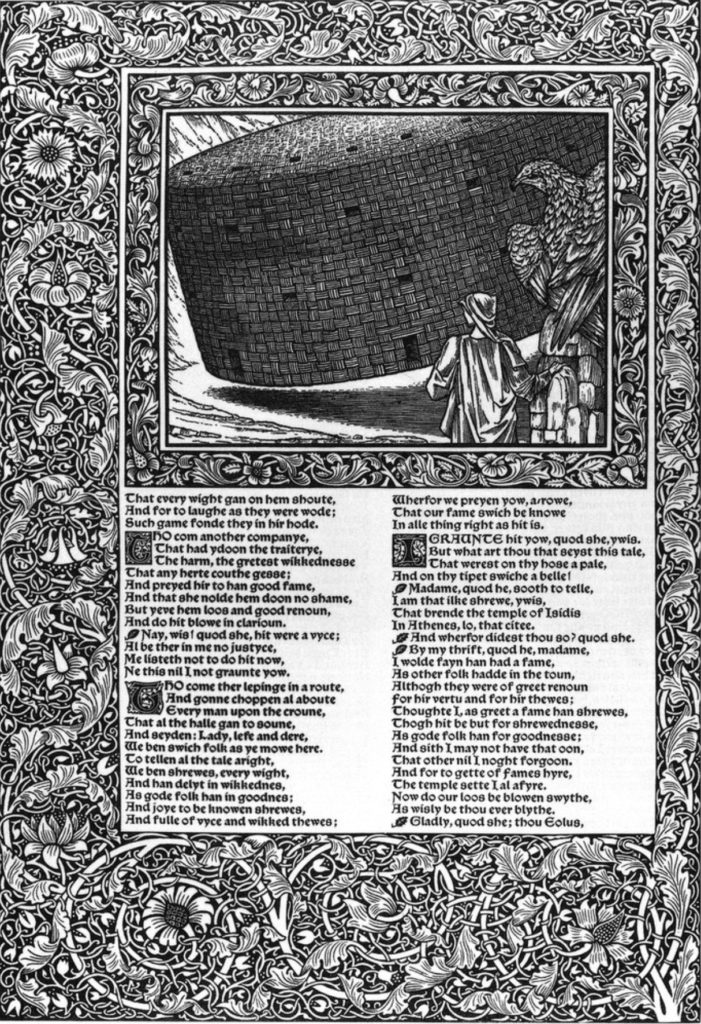

Digitized Manuscript & Shelfmark

London, British Library, Cotton Nero MS a.x f.94v-130r.

Further Reading

Brody, Richard. “The Green Knight, Reviewed: David Lowery’s Boldly Modern Revision of a Medieval Legend.” The New Yorker: The Front Row (8/3/2021).

Cybulskie, Danièle. “Medieval Movie Review: The Green Knight.” Medievalists.net (7/2021).

Dahm, Murray. “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in the Movies.” Medievalists.net (1/2021).

Fahey, Richard. “Bobbing For Answers.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame: Medieval Institute (2/26/2015).

Grady, Constance. “The Magic, Sex, and Violence of the 14th-century Poem Behind The Green Knight.” Vox (7/29/2021).

Harty, Kevin J. “The Green Knight, dir. David Lowery (2021).” Medievally Speaking (8/10/2021).

Hilmo, Maidie. “The Colors of the Pearl-Gawain Manuscript: The Questions that Launched a Scientific Analysis.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame: Medieval Institute (1/12/2014).

Johnson, Weldon B. “How ‘The Green Knight,’ Set in the Days of King Arthur, Takes a Modern Look at Masculinity.” Arizona Central (7/28/2021).

Lawson, Richard. “The Green Knight Is This Summer’s Best Medieval Meditation on Death.” Vanity Fair (7/28/2021).

Martin, Elyse & Sean Rubin. “Chivalry and Medieval Ambiguity in The Green Knight.” Tor (8/10/2020).

—. “Medievalists Ask Five Questions About A24’s The Green Knight.” Tor (6/1/2020).

Nelson, Ingrid. “The Green Knight” and The Green Knight.” Medium.com (7/28/2021).

Olsen, Mark, Chang, Justin, Yamato, Jen. “Did You Love or Loathe ‘The Green Knight’? Either Way, You’re Not Alone.” Los Angelos Times (8/7/2021).

Ouellette, Jennifer. “Review: The Green Knight Weaves a Compelling Coming-of-age Fantasy Quest.” Ars technica (7/31/2021).

Perry, David M. & Matthew Gabriele. “The Green Knight Adopts a Medieval Approach to ‘Modern’ Problems.” Smithsonian Magazine (8/23/2021).

Trigg, Stephanie. “The Poem Behind The Green Knight.” Pursuit (8/27/2021).

Wilkinson, Alissa. “The Green Knight is Glorious and a Little Baffling. Let’s Untangle It.” Vox (7/30/2021).