[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

A collection of poems written nearly 700 years ago may at first seem entirely outdated in subject matter, but there are certain aspects of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales that are alarmingly relevant in today’s world despite our wishes that they had stayed in the past. One such element is the way in which countless characters tell their tales about women. In many of the tales, women are denied a nuanced voice and a complex character in favor of being reduced to overly idealized deities or spiteful, manipulative villains. It is the former representation of women and its manifestation through one particular character that serves as the subject of this post. Grisilde of “The Clerk’s Tale,” a tale about a man who routinely challenges (and emotionally abuses) his wife to test her goodness and her love for him, is a prime example of a woman who is seen only in idealized descriptions and as a figment of her husband’s male fantasy. In modern film and literary criticism, there is a term that describes the type of character Grisilde is and the role she plays in her tale: the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG).

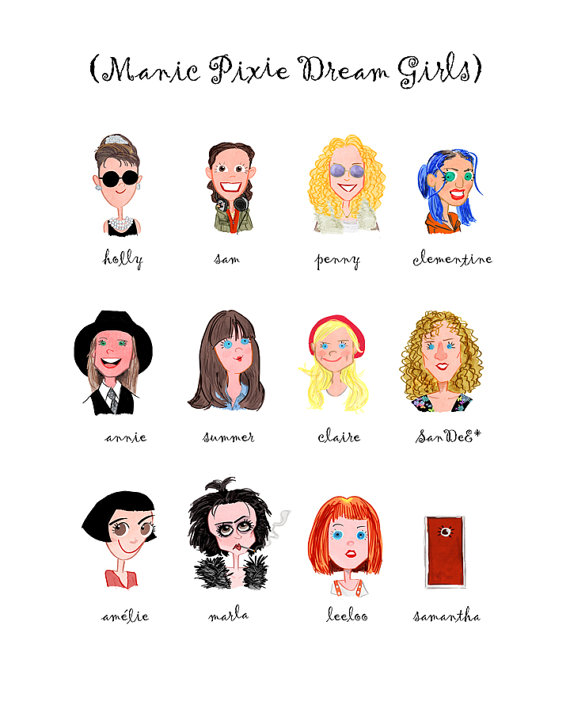

Nathan Rabin, a film critic for The AV Club, coined the term “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” in a 2007 review of the film Elizabethtown. He writes, “The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures” (Rabin). This type of woman typically is chic in appearance, has cutting edge taste in the arts, and practices hobbies that set her apart from other women. Some recognizable examples of MPDGs from film are represented in the image below, and the popularity of the films in which these characters appear has catalyzed the term’s use outside exclusively critical circles.

In the decade since Rabin first coined the term, it has become a staple of discussions about female characters in popular culture, inspiring everything from internet quizzes to entire novels written with the intention of dismantling the archetype.

However, while Rabin describes the archetype in terms of its place within cinematic history, Grisilde’s role in “The Clerk’s Tale” works to suggest that this concept, which has become such a common trope in modern culture, has actually been in existence for well over half a century. In fact, Hugo Schwyzer hints at this in an article for The Atlantic, writing, “As contemporary a trope as it feels, it’s as old as Dante with his vision of being guided through paradise by his saintly Beatrice” (Schwyzer). Despite her name, which is much more unique than that of her husband, Walter, Grisilde lacks the quirky personality that commonly defines a MPDG by today’s standards—it would have been entirely unbelievable rather than merely eccentric to find a ukulele-strumming, pierced-eared woman in medieval England. Instead, Grisilde is remarkable in her perfection and her purity, both of which are emphasized to set her apart from other women, a staple of the MPDG genre. Walter does not ever want to take a wife, but Grisilde, because she possesses some otherworldly qualities, is the only woman who can get through to Walter and allow him to see the merits that accompany having a wife. Walter, emulating a medieval Gatsby, creates an image of Grisilde in his head that paints her as more than a person. Chaucer writes:

Commending in his heart her womanly qualities

And also her virtue, passing any person…

…and decided that he would

Wed her only, if ever he should wed. (Chaucer 239-245)

While Grisilde fits an altered version of the MPDG personality that more appropriately matches the time period from which she is a product, she fits the other half of the modern definition to a tee. Her sole function in the narrative of “The Clerk’s Tale” is as part of the journey of the male characters. For the Clerk, she serves as an example of the types of characteristics all women listening to his tale should aspire to possess. For Walter, her husband in the tale, she is a means through which he attempts to achieve his own happiness and self-assurance without regard to her feelings. Prior to getting married, Walter says the following to Grisilde:

I say this: are you ready to submit with good heart

To all my desires, and that I freely may,

As seems best to me, make you laugh or feel pain,

And you never to grouch about it, at any time? (Chaucer 351-354)

Walter goes on to make Grisilde swear that she will never say no when he wants her to say yes. He desires to better understand the world and feel secure of his place within it, and in order to do so, he consistently tests Grisilde’s affections for him and stretches the lengths to which she will go to keep him content. Grisilde watches as her children are taken away and is even willing to see her husband marry another woman if it will make him happy.

Chaucer attempts to remedy some of the damage done through the decimation of Grisilde’s character by urging women in his envoy to “let no humility nail down your tongue” (Chaucer 1184). In comparison to the rest of “The Clerk’s Tale,” Chaucer’s envoy dovetails well with aspects of modern feminism. It also fits, however, in accordance with the common portrayal of modern MPDGs as bold women who have something to say and who will not let humility nail down their tongues. Unfortunately, the things these women have to say are most often pieces of advice as to how their male protagonist can improve his life. For example, Natalie Portman’s character in Garden State, commonly accepted as an exemplum of the MPDG, is permitted to scream at the top of her lungs, but only after the male lead figures out his current purpose in life and takes her hand.

This type of representation in which female characters are reduced to personality quirks and pithy advice aimed at male protagonists remains problematic today because it paints women as vessels through which men can accomplish their needs and strips them of any independent ambitions. In Grisilde’s marriage, as in the relationships of countless other MDPGs, she has no agency in making the choices that better her own life. Rather, she and women such as Woody Allen’s Annie Hall and Cameron Crowe’s Penny Lane continue to stand as a means through which a man can determine who he is, what he wants out of life, and how the woman to whom he is magnetically attracted can help him to obtain his deepest desires.

Kelsey Dool

University of Notre Dame