The flare of recent racial tensions, especially in the wake of the Trump administration’s xenophobic rhetoric, has had repercussions in Charlottesville and across the United States. White nationalist organizations, such as the Alt-Right, have become the face of this hatred and have renewed national concern about the nature of race relations and prejudices in the United States. And of course, the internet has opened new windows and doors into impressionable minds and offered these groups new ways to the spread their toxic rhetoric.

As medievalists it is especially important that we do our part to counter the way in which White supremacist organizations, who have historically appropriated medieval literature into their rhetoric of hatred. It falls especially to Anglo-Saxonists, who have historically been caught in an unfortunate web of association with White Supremacist rhetoric, to explicitly set the record straight and to offer alternative models of medieval thinking about race and ethnicity. The fact is that 20th century Anglo-Saxonist scholarship has intellectually contributed—even helped to create—the romantic idea of the ‘Germanic hero’ (whether in the paragons of Beowulf or Siegfried), and without the work of literary and linguistic scholars of Germanic philology, Hitler’s Nazi rhetoric regarding the racial superiority of an imaged ‘Aryan race’ may not have been possible or at the very least may not have had the same type of intellectual traction.

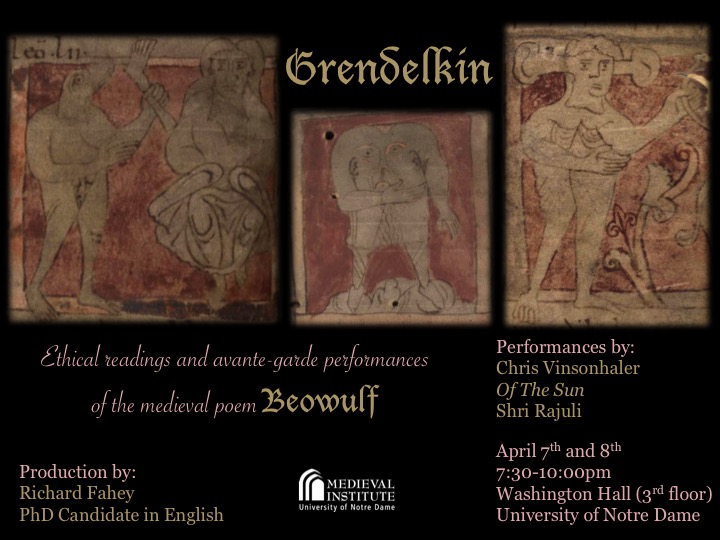

Moreover, the persistent assumption that medieval people in Europe were necessarily racist, and that they collectively held attitudes of racial superiority congruent with modern White supremacist groups, is both dangerous and non-factual. This assumption contributes to the narrative that ethnic Europeans always considered themselves to be somehow cultural better than their neighbors to the south and east. With all this in mind, I wish to return to the sources—to a medieval text from Anglo-Saxon England—in order to reflect on racial attitudes and prejudices in so far as the text presents them. My discussion will center primarily the Old English The Wonders of the East, an Anglo-Saxon translation of the Latin De rebus in Oriente mirabilbus, which catalogues wondrous places, peoples and creatures from far way lands, generally somewhere in Africa or Asia.

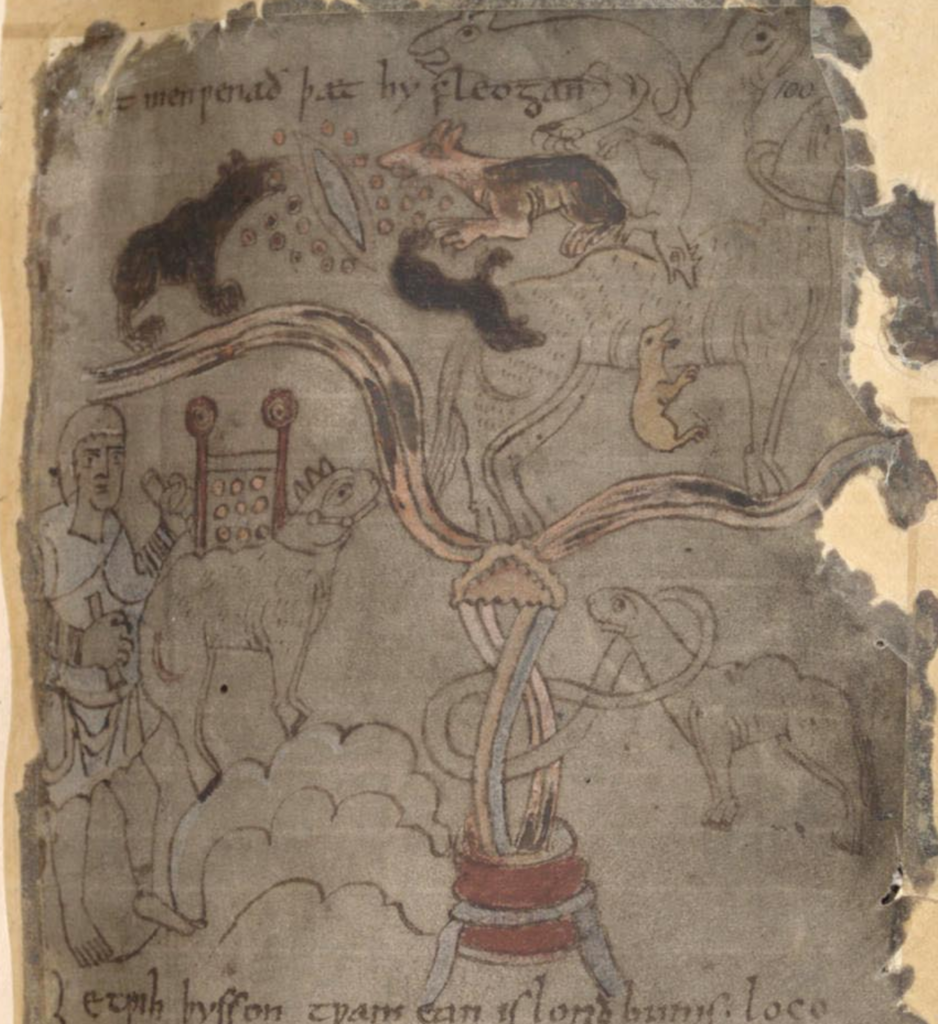

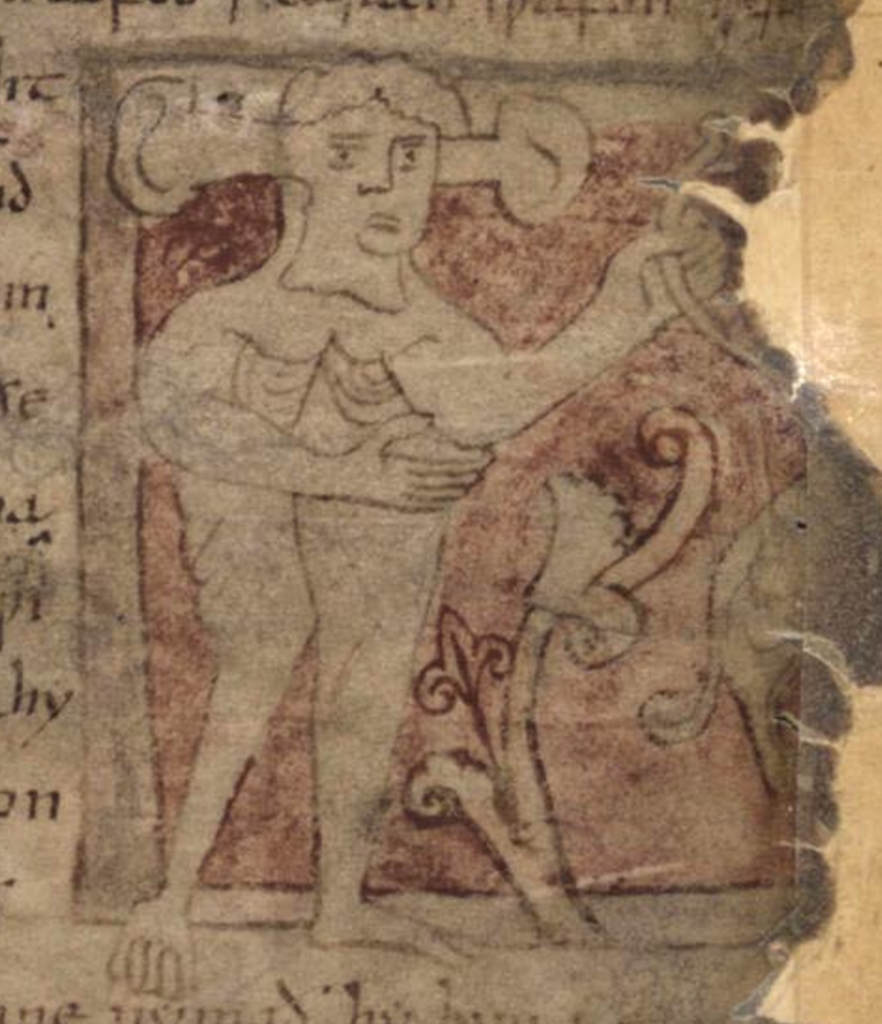

Scholars Susan M. Kim and Asa Mittman have argued that Anglo-Saxon audiences would have likely considered the wonders described in the texts as truly existing and point out that, “the very status of the Wonders as wonders implies at once the stretching of possibility, and an insistence on the viability of the same possibility, at once the incredibility and the truth of the narrative” (1), leading to the conclusion that “the Anglo-Saxon readers and viewers of these texts probably considered them true” (2). The British Library agrees and states in their blog, describing the monsters illustrated in the Wonders: “belief in the existence of monstrous races of human beings was central to medieval thinking, although almost everything about them was open to debate and discussion.”

The Liber Monstrorum, a Latin text similarly interested in monsters and wonders and which Michael Lapidge has argued was composed in Anglo-Saxon England, presents his marvels with more skepticism. Its opening disclaimer casts serious doubt regarding the veracity of many of the marvels described and offers an alternative perspective noting that quaedam tantum in ipsis mirabilibus uera esse creduntur “only certain things in the wonders are believed to be true” and that most may in fact be rumoroso sermone tamen ficta “nevertheless rumor by false speech.”

But, what about when one encounters a ‘wonder’ in a medieval text which (however distortedly) attempts to discuss a group of people or species of animal, which does exist in places far from Europe? What does it say about racial attitudes in Anglo-Saxon England if an ethnic group—such as Ethiopians—is included in a catalogue of monsters? How might we read this?

Before we get to the passage describing the sigelwara ‘Ethiopians,’ let’s begin by briefly discussing the text as a whole and some of the other wonders in the collection. The Old English Wonders is found in two manuscripts, (BL, Cotton Tiberius b.v and BL, Cotton Vitellius a.xv—often called the Nowell Codex or simply the Beowulf-manuscript). One of the monstrous people included in the text is the blemmyae, known explicitly from the Latin source text but left unnamed in the Old English Wonders. What makes these people wondrous is their unusual physical appearance. It is said of these people:

| Old English Prose | Modern English Translation |

| Þonne syndon oþre ealond suð from Brixonte, on þon beoð men acende buton heafdum, þa habbað on hyra breostum heora eagan ond muð. Hy seondon eahta fota lange ond eahta fota brade. Ðar beoð dracan cende þa beoð on lenge hundteontige fot-mæl longe and fiftiges; hy beoð greate swa stænene sweras micle. For þara dracaena micelnesse ne mæg nan man na yþelice on þæt land gefaran. | Then there is another island, south of the Brixontes, on which there are born men without heads who have their eyes and mouth in their chests. They are eight feet tall and eight feet wide. There are dragons born there which are one hundred and fifty feet in length, and are as thick as great stone pillars. Because of the abundance of the dragons, no one can journey easily in that land. |

The blemmyae are pretty unbelievable by modern standards, and today we would recognize such creatures as a fiction or fabrication derived more likely from the imagination than from experience. Emphasis is on the peculiar placement of his face and his enormous size, which is followed up by the corresponding reference to the enormous dragons also found in the wondrous domain of the blemmyae.

Physical description is front and center in the description of the panotii, another unnamed people known from the Latin source text. The panotii are described as follows:

| Old English Prose | Modern English Translation |

| Þonne is east þær beoð men acende þa beoð on wæstme fiftyne fota lange ond x on brade. Hy habbað micel heafod ond earan swæ fon. Oþer eare hy him on niht underbredað, ond mid oþran hy wreoð him. Beoð þa earan swiðe leohte ond hy beoð swa on lic-homan swa white swa meolc. Gyf hy hwilcne mannan on þæm lande geseoð oðþe ongytað, þonne nymað hy hyra earan him on hand ond fleoð swiðe, swa hrædlece swa is wen þæt hy fleogen. | Going east from there is a place where people are born who are in size fifteen feet tall and ten broad. They have large heads and ears like fans. They spread one ear beneath them at night, and they wrap themselves with the other. Their ears are very light and their bodies are as white as milk. And if they see or perceive someone in their lands, they take their ears in their hands and flee far, so quickly that the belief is that they flew. |

These wondrous people are likewise described as monstrous in size and are identified by their unusual facial features, namely large heads and fan-shaped ears. They are described also as having milky white bodies, and so here reference to skin color is one of the ways in which the text physically depicts and characterizes the racialized panotii. The passage goes on to describe their peculiar sleeping habits and speedy flight whenever they sense anyone in their territory.

Another group of people, described in the Wonders as hostes, Latin for ‘enemies,’ are also described firstly by their physical features—in this case their huge size and dark skin—and only after is the reference to their cannibalism.

| Old English Prose | Modern English Translation |

| Begeondan Brixonte ðære ea, east þonon beoð men acende lange ond micle, þa habbað fet ond sconcan xiifota lange, sidan mid breostum seofan fota lange. Hi beoð sweartes hiwes, ond Hostes hy synd nemned. Cuþlice swa hwlycne man swa hi læccað, þonne fretað hi hyne. | Beyond the River Brixontes, east from there, there are people born big and tall, who have feet and shanks twelve feet long, flanks with chests seven feet long. They are of dark color, and are called Hostes. As surely as they catch someone they devour him. |

In this passage, we are told of a people who are to a certain extent characterized by skin color, and so the racial element has now come into play—even violent racialization. In this example, we have reference to a group of dark-skinned cannibals. Still, it seems that, at least according the Wonders, the monstrous hostes are to be feared not because of their “race” or the color of their skin, but rather on account of their potentially life-threatening behavior. Nevertheless, this is a clear racialization and monsterization of the gigantic Hostes.

Another reference to dark-skinned people in the Wonders describes a group who live upon a marvelous mountain:

| Old English Prose | Modern English Translation |

| Ðonne is oðer dun þær syndon swearte menn, ond nænig oðer man to ðam mannum geferan mag forðam þe seo dun byð eall byrnende. | Then there is another mountain where there are dark people, and no one else can travel to those people because the mountain is everywhere burning. |

Here what seems wondrous is the mountain, described as ‘everywhere burning’ and possibly the fact that these people are able to live in such an inhospitable environment. While this is certainly a racialization of these peoples, I would suggest that what is being most marveled at is the mountain and the way it protects these inhabitants, and perhaps least of all that these people are described as swearte—‘swarthy’ or ‘dark’ in Old English.

Which brings us, at long last, to the passage on sigelwara or ‘Ethiopians’ in the Wonders, which begins not with reference to these people, but rather to the nearby marvelous trees, on which gemstones are said to grow.

| Old English Prose | Modern English Translation |

| Ðonne is treowcyn on þæm þa deorwyrþystan stanas synd of acende, þonon hy growað. Þær þa moncyn is seondan sweartes hyiwes on onsyne, þa mon hateð sigelwara. | Then, there is a kind of tree, which grows there, on which the most precious stones sprout. There is also a group of people there of dark color in appearance, who are called Ethiopians (sigelwara). |

Indeed it is the jewel-producing trees, which are the true wonder in this section, and the reference to the sigelwara appears as something of an afterthought, though they are characterized entirely based on their skin color, and therefore highly racialized. This physical feature is mentioned before the text promptly transitions to the next wonder in the collection.

Nevertheless, the Old English Wonders refers to Ethiopians in its list of marvels, and I would argue the text is most guilty of exoticism as it reflects a sense of wonder about different groups of people without any reference to respective racial superiority or inferiority. That these people were from a far away place and are described as visually different seems only to heighten the interest and intrigue. In other words, the Ethiopians are a wondrous people.

It is true that with the Wonders, we have a text that racializes and characterizes groups of people based on their physical characteristics, and so the text is—or at least can be read as—racist in this sense. However, it is important to note that white-skinned people are just as wondrous (or monstrous) as dark-skinned people in the text, primarily made marvelous by their status as strange, foreign and other. The Wonders demonstrates medieval fascination with the exotic and the marvelous, and the spatial orientation of the text may even reflect a desire to be elsewhere. Indeed, certainly in Anglo-Saxon England as with most of medieval Europe, people considered themselves to be living in something of a cultural backwater, and places to the south and east (whether cities such as Rome, Constantinople, Baghdad, or regions such as Ethiopia or India) were considered culturally superior in that they were places full of knowledge and wonders.

While the Old English Wonders of the East should by no means be taken as a representative of all medieval people’s perception or interest in exotic wonders (as no single text could), it nevertheless tells a somewhat different story about racial attitudes in Anglo-Saxon England than the narratives pushed by modern Neo-Nazi and White Supremacist groups, who we all know are the real monsters.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited:

British Library’s “Monsters and Marvels in the Beowulf Manuscript” (2013).

Fulk, R. D. The Beowulf Manuscript. Dumbarton Oaks, 2010: 16-31.

Mittman, Asa Simon. ‘Are the ‘monstrous races’ races?’ Postmedieval 6:1 (2015): 36-51.

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf Manuscript. 1995.

MANSCRIPT SHELFMARKS:

London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius b.v fols.78v-87r.

London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius a.xv fols.98v-106.