George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones is currently one of the most popular fantasy series, both on television and in print, and some have begun to describe the work alongside J. R. R. Tolkien‘s Lord of the Rings and J. K. Rowling‘s Harry Potter. As with Tolkien and Rowling, Martin borrows readily from medieval history and literature, but somewhat differently; Martin seems at times to invert certain fantasy genre expectations and stereotypes. His fantasy series centers on themes generally associated with modern medievalism, especially issues of rightful rulership, noble lineage, courtly politics, codes of chivalry, medieval warfare, ancient prophecy, arcane magic, mysterious monsters and spiritual mysticism. However, Martin’s somewhat more innovative characterizations and reimagining of traditions are what I have personally found most enjoyable about reading Song of Ice and Fire and viewing Game of Thrones.

In particular, I appreciate how Martin highlights the failure of the patriarchy. At the beginning of Game of Thrones (both the book and the film), most of the powerful houses and many of the kingdoms are ruled by strong men—the seven kingdoms and the stormlands under Robert Baratheon, the north under Eddard Stark, the westerlands under Tywin Lannister, the iron islands under Balon Greyjoy, and the Dothraki khalasar under Khal Drogo. Even the exiled Viserys Targaryen held his family’s claim to the iron throne, though he could hardly be considered strong in any sense.

The one possible exception is the queen of thorns, Olenna Tyrell, who is ultimately poisoned by Jamie Lannister after allying with Daenerys Targaryen in season seven, episode three [“The Queen’s Justice”]. Like her grandmother, the thrice-made queen, Margaery Tyrell, also demonstrates her social prowess by navigating courtly politics and leveraging marriage to her advantage, working the system from within. However, Margaery underestimates her enemies and becomes a victim of the wildfire arson of the Sept of Balor, which all but destroys her family, sparing only Olenna who was then safe at Highgarden and beyond Cersei’s reach.

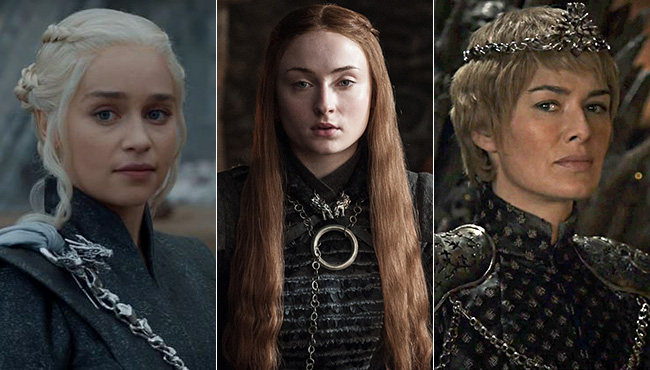

By the end of the series, things look quite different. The final contest for the iron throne is staged between two rival queens, Daenerys Targaryen and Cersei Lannister. The once exiled Daenerys, having been fostered by the Dothraki, holds perhaps the strongest claim to the iron throne, though Jon Snow’s recently discovered identity certainly complicates the matter of succession as determined by the patriarchal legal traditions of Westeros. Nevertheless, Daenerys has emerged as a conqueror in Essos and returns to Westeros with both armies and dragons.

The Baratheon family is mostly wiped out in the war of five kings (although Daenerys names Gendry Baratheon the new lord of Storm’s End), and the north and riverlands seem to be led by Sansa Stark, despite Jon Snow’s recent title as king in the north. Cersei Lannister retains the iron throne as queen, and she commands her family’s forces as well as the Iron Fleet of Euron Greyjoy and the mercenary guild known as the Golden Company. Asha Greyjoy (or Yara in the films) is also named queen of the iron islands, and she has acted as a leader throughout the series, as has the Dornish matriarch, Ellaria Sand (a character loosely associated with princess Arianne Martell, absent from the films entirely). And, after Ned Stark’s death, Catelyn Stark took command of the north and riverlands alongside her son Robb Stark until the terrible red wedding claims both their lives.

Other prominent female characters have likewise developed into formidable figures, especially the fearless assassin Arya Stark, who crucially slays the Night King, the mighty knight Brienne of Tarth, and the mystical red priestess Melisandre. The young and fierce Lyanna Mormont also shows her unfailing fortitude, even as she dies heroically during the battle for Winterfell in a David and Goliath allusive scene, in which she destroys an undead giant.

I am by no means attempting to exonerate Game of Thrones or Song of Ice and Fire from warranted allegations of sexism, and there is surely still much to reflect on and criticize in this regard. More blatantly, it seems that Game of Thrones is distinctly less concerned with issues of race. The films in particular consistently portray the Dothraki as exceptionally savage in a manner that upholds extremely harmful and problematic stereotypes. This characterization is especially troubling considering how in season eight, episode three [“The Long Night”], the Dothraki are essentially sacrificed. The much discussed Dothraki charge into the approaching forces of the Night King was the first and only assault by the living against the army of the dead, and the Dothraki were all but annihilated as a result. Rather miraculously, the one Westerosi knight who rides out with the Dothraki manages to make it back alive.

Martin consistently focuses on the gritty human experience, and most of his cultures seem barbaric in one form or another. However, especially in the film, the Dothraki are presented at times in ways that reinforce a stubborn racial bias within the modern fantasy genre. It seemed to me as a reader that in the book series, Song of Ice and Fire, Martin is able to better demonstrate that savagery and the horrors which humans inflict on each other are ubiquitous and extend to every culture—perpetrated by the free folk wildlings north of the Wall, the feudal Westerosi and the pillaging iron islanders, as often as by the Dothraki horde or the ruling class in Slaver’s Bay. Of course, I fully concede that my interpretations of the books and films are necessarily limited and affected by my white male privilege, as it is for the books’ author [George R. R. Martin] and films’ creators [David Benioff and D. B. Weiss]. It nevertheless seems apparent that the various patriarchal systems are the universal root of atrocities in both Westeros and Essos.

It must be emphasized, as many critics have pointed out, that the film series repeatedly underrepresents persons of color. The only two major non-white characters that make it to season eight are Grey Worm, who leads the Unsullied, and Missandei, who dies at Cersei’s hand this past weekend, after being captured by Euron Greyjoy during season eight, episode four [“The Last of the Starks”]. Both are former slaves from Essos who have become loyal friends and advisors to Daenerys. Missandei’s devotion to the “mother of dragons” costs her life, and I would be rather disappointed, if not surprised, should the same prove true for Grey Worm before the war for Westeros is done.

Perhaps as unfortunate as Game of Thrones’ mistreatment of Missandei and Grey Worm is the book series’ numerous characters of color who simply do not feature in the show, including central figures from the Dornish royal family and Moqorro, a powerful red priest from Volantis, who is searching for Daenerys in Martin’s book five, A Dance with Dragons. The film also misses a number of opportunities to cast major protagonists from Essos as persons of color, including Varys, Thoros of Myr and Melisandre, all of whom are played by white actors.

While Game of Thrones falls woefully short when it comes to fantasy representations of diverse and non-white cultures, and above all underrepresents women of color, it does seems to me that the toppling of the patriarchy by powerful (generally white) women is part of its narrative design. In virtually every case, with the notable exception of Cersei, female rulership is a marked improvement upon the patriarchy that existed prior to women’s rise to power in Westeros. In my opinion, even Cersei seems objectively preferable to her son Joffrey Baratheon, the adolescent-king poisoned by Littlefinger [Petyr Baelish] and Olenna Tyrell at his own wedding.

Indeed, as the show nears its end, three formidable women—Daenerys Targaryen, Sansa Stark and Cersei Lannister—are best positioned to win the game of thrones. I hope that the fact that an anti-patriarchal message, however clumsily handled, features so prominently in a mainstream fantasy series may at the very least represent an evolution in contemporary audiences’ expectations and sensibilities. In addition to the series’ function as a literary bridge between the modern and medieval for many readers and students, the bifurcating successes and failures with regard to expressions of feminist and racial attitudes in Game of Thrones make the film a potentially useful teaching tool for illustrating conscious and unconscious misogyny and racism in medievalism and fantasy literature.

Hopefully, they do not blow it and put Jon Snow on the iron throne.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate in English

University of Notre Dame

Related Online Reading:

Adair, Jamie. “Is Chivalry Death?” History Behind Game of Thrones (November 10, 2013).

Ahmed, Tufayel. “Why Women Will Rule Westeros When the Show Ends.” Newsweek (June 22, 2016).

Ashurst, Sam. “Game of Thrones: Who’s Got Magical Powers, and What Can They Actually Do?” Digital Spy (July 20, 2017).

Baer, Drake. “Game of Thrones‘ Creator George R. R. Martin Shares His Creative Process.” Business Insider (April 29, 2014).

Blaise, Guilia. “Games of Thrones Has a Woman Problem (And It’s Not What You Think).” The Huffington Post (May 6, 2017).

Blumsom, Amy. “Arya Stark’s Kill List: Who’s Still Left for Needle in Game of Thrones Season 8?” The Telegraph (May 5, 2019).

Bogart, Laura. “Margaery Tyrell is Westeros’ Biggest Badass—and the Show Can’t Handle Her.” AV Club (May 23, 2016).

Bundel, Ani. “What Happened to Yara Greyjoy in Game of Thrones‘ Season 7? Here’s Your Official Refresher.” Elite Daily (April 5, 2019).

Chaney, Jen. “Has Game of Thrones Solved Its Woman Problem?” Vulture (June 6, 2016).

Chang, David. “Game of Thrones Continues Feminist Tone.” The Observer (April 26, 2019)

Chen, Heather, and Grace Tsiao. “Game of Thrones: Who is the True Heir?” BBC News (August 29, 2017).

Corless, Bridget. “The Romans, the Walls and the Wildlings.” History Behind Game of Thrones (August 9, 2019).

E., Marjorie. “Game of Thrones and the Struggle with Liking Sexist Television.” Femestella (February 18, 2019).

Engelstein, Stefani. “Is Game of Thrones Racist?” Medium. Duke University (April 10, 2019).

Dessem, Mathew. “Here’s Why the Dothraki Attack in Game of Thrones Was So Devastating.” Slate (April 30, 2019).

Dikov, Ivan. “Game of Thrones is Terrific But Why Are Humans So Enchanted With Feudalism?” Archaeology in Bulgaria (October 19, 2017.)

Fahey, Richard. “Zombie of the Frozen North: White Walkers and Old Norse Revenants.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (March 5, 2018).

Flood, Rebecca. “George R. R. Martin Revolutionised How People Think About Fantasy.” The Guardian (April 10, 2015).

Gay, Verne. “Game of Thrones: 14 Great Supernatural Moments and Creatures.” Newsday (April 7, 2016).

Guillaume, Jenna. “People Are Calling Game of Thrones‘ Season Eight, Episode 4 the Worst Episode Ever.” Buzzfeed News (May 6, 2019).

Harp, Justin. “Nathalie Emmanuel Says Early Game of Thrones Was ‘So Brutal to the Women.'” Digital Spy (December 4, 2019).

Hawkes, Rebecca. “Melisandre: Everything You Need to Know About the Red Woman’s Shock Return to Save Winterfell in Game of Thrones.” The Telegraph (April 30, 2019).

—. “Game of Thrones and Race: Who Are the Non-White Characters and Where Are They from in the Books and Show?” The Telegraph (April 29, 2019).

Heifetz, Danny. “The Dothraki Deserved Better From Daenerys.” The Ringer (April 30, 2019).

Izadi, Elahe. “Sansa Stark Should Sit on the Iron Throne in Game of Thrones— and it Looks Like She Might.” The Washington Post (May 1, 2019).

Khan, Razib. “Is Game of Thrones Racist? Not Even Wrong…” Discover (April 21, 2011).

Kim, Dorothy. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In the Middle (August 28, 2017).

Lash, Jolie. “Game of Thrones: Is Daenerys Targaryen a Good Ruler?” Collider (April 16, 2019).

Liao, Shannon. “Game of Thrones Has Spent Three Years Foreshadowing the Long Night’s Ending.” The Verge (May 1, 2019).

—. “Daenerys vs. Cersei: Who Has the Resources to Win the Final Game of Thrones?” The Verge ( April 29, 2019).

—. “Game of Thrones’ Greatest Hero is Still Olenna Tyrell.” The Verge (July 24, 2017).

Lomuto, Sierra. “Public Medievalism and the Rigor of Anti-Racist Critique.” In the Middle (April 4, 2019).

London, Lela. “What Are the Seven Houses in Game of Thrones and Who Rules Westeros?” The Telegraph (May 6, 2019).

Majka, Katie. “Fight Like a Lady: The Promotion of Feminism in Game of Thrones.” Fansided: Winter is Coming (May 7, 2018).

Michallon, Clémence. “Game of Thrones: George R. R. Martin Explains How Arya Stark’s Character Was Inspired by Feminism and the Sexual Revolution.” Independent (April 22, 2019).

Miller, Julie. “Which Historical Event Inspired Game of Thrones‘ Shocking Death Last Night?” Vanity Fair (April 14, 2014).

Nelson, Isis. “White Saviorism in HBO’s Game of Thrones.” Medium (August 1, 2016).

Nkadi, Ashley. “Why Is Society Intent on Erasing Black People in Fantasy and Sci-Fi’s Imaginary Worlds?” The Root (November 9, 2017).

Pavlac, Brian A. Game of Thrones Versus History: Written in Blood. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2017.

Philippe, Ben. “Missandei, Grey Worm, and Game of Thrones‘ Racial Blind Spot.” Vanity Fair (April 22, 2019).

Pitts, Kathryn. “Women of Color in Game of Thrones: A Show of Underrepresentation.” Sayfty (April 7, 2017).

Plante, Corey. “Why Grey Worm Will Probably Die in Game of Thrones Season 8, Episode 4.” Inverse (May 4, 2019).

Reisner, Mathew. “Game of Thrones Meets International Relations: A Match Made in Heaven?” The National Interest (April 3, 2019).

Renfro, Kim. “Fans are Furious Over This Game of Thrones Plotline, and It’s Not Hard to See Why.” Business Insider (April 25, 2016).

—, and Skye Gould. “Why John Snow Has Always Been the ‘Rightful Heir’ to the Iron Throne.” Insider (August 29, 2017).

Robinson, Garrett. “Fantasy Genre Hates Women.” Medium (February 4, 2016).

Robinson, Joana. “Game of Thrones: Why the Latest Death Stings So Much.” Vanity Fair (May 5, 2019).

Romano, Aja. “Game of Thrones‘ Missandei Controversy, Explained.” Vox (May 6, 2019.)

Romero, Ariana. “Your Guide to Game of Thrones‘ Most Pressing Prophecies.” Refinery29 (April 3, 2019).

Rossenberg, Alyssa. “The Arguments about Women and Power in Game of Thrones Have Never Been More Unsettling.” The Washington Post (August 9, 2017).

Ruddy, Matthew. “10 Reasons Why Cersei Lannister is the Strongest Character on Game of Thrones.” Screenrant (April 29, 2019).

Rumsby, John H. “Otherworldly Others : Racial Representation in Fantasy Literature.” Masters Thesis: Université de Montréal (2017).

Ryan, Lisa. “Brienne of Tarth Finally Gets What She Deserves.” The Cut (April 22, 2019).

Schuessler, Jennifer. “Medieval Scholars Joust with White Nationalists. And On Another.” New York Times (May 5, 2019).

Sturtevant, Paul B. “You Know Nothing About Medieval Warfare John Snow.” The Public Medievalist (May 2, 2019).

Thomas, Ben. “The Real History Behind Game of Thrones, Part 3: Slaver’s Bay.” The Strange Continent (May 4, 2019).

Thomas, Rhiannon. “In Defense of Catelyn Stark.” Feminist Fiction (August 9, 2012).

Thompson, Eliza. “A Guide to the Many Religions on Game of Thrones.” Cosmopolitan (July 13, 2013).

Tucker, Christina. “Last Night’s Episode of Game of Thrones Was a Failure to Women.” Elle (May 6, 2019).

Vineyard, Jennifer. “Lyanna Mormot, Giant Slayer, Never Expected to Last This Long.” The New York Times (April 30, 2019).

—. “Game of Thrones: Grey Worm’s Fate Surprised Everyone But the Man Who Plays Him.” The New York Times (April 29, 2019).

—. “Game of Thrones: Why Do the Wildlings and the Night’s Watch Hate Each Other So Much?” Explainers (June 8, 2014).

Waxman, Olivia B. “Game of Thrones is Even Changing How Scholars Study the Real Middle Ages.” Time (July 14, 2017).

—. “An Exclusive Look Inside Harvard’s New Game of Thrones-Themed Class.” Time (May 30, 2017).

Weeks, Princess.”Game of Thrones Delivers Its Worst Episode of the Season While Screwing Over Its Female Characters.” The Mary Sue. (March 6, 2019).

—. “We Need to Talk About How Game of Thrones Treats the Dothraki.” The Mary Sue. (April 29, 2019).

Yadav, Vikash. “A Dothraki Complaint.” Duck of Minerva (April 27, 2012).

Yglesias, Matthew. “Game of Thrones‘ Dany/Dothraki Storyline Doesn’t Make Any Sense.” Vox (June 3, 2016).

Young, Helen. “Game of Thrones‘ Racism Problem.” The Public Medievalist (July 21, 2017).

“The Dothraki and the Scythians: A Game of Clones?” The British Museum Blog (July 12, 2017).

“Game of Thrones‘ Red Wedding Based on Real Historical Events: The Black Dinner and Glencoe Massacre.” Huffington Post. (June 5, 2013).

“Huns, Mongols and Dothraki.” Tower of the Hawk (April 7, 2015).

“The Iron Islands and the Viking Age: Gods, Wives, and Reavers.” Tower of the Hawk (April 7, 2015).

“Love, Fear and Humanity and the Ballad of Grey Worm and Missandei.” Watchers on the Wall (February 15, 2018).