Few people, even Floridians, know about the medieval roots of St. Augustine discussed in my previous blog. In fact, if you’re planning a trip there and you Google “medieval St. Augustine,” you’ll only get results for the city’s Medieval Torture Museum or for the antique Christian philosopher St. Augustine of Hippo.

As readers of this blog know well, though, there is far more to any society, medieval or otherwise, than its methods of policing and punishment. Allow me, then, to take you on a medievalist’s tour of St. Augustine!

I recommend beginning at the St. Augustine Visitor Information Center. The parking is plentiful (though not free), the air conditioning glorious, and the informational brochures abundant. The VIC also has terrific museum-quality exhibits, including replicas of Spanish sailing ships and plenty of historical documents, explanatory placards, and artifacts. The plaza also houses a notable fountain, a replica of the Fuentos de los Caños de San Francisco (Fountain of the Spouts, in the Avilés neighborhood of San Francisco). St. Augustine’s sister city, Avilés, Spain, also the birthplace of St. Augustine’s founder Pedro Menéndez, gifted the fountain to St. Augustine in 2005. The original Fuentos de los Caños de San Francisco in Avilés was built in the sixteenth century, in the late medieval/early modern transitional period, and will set the medieval mood quite well for you!

The Castillo de San Marcos

From the VIC you can walk east to the Castillo de San Marcos (the Fort of St. Mark, managed by the National Park Service). As you’ll see in your visit, the Castillo blends the functions of medieval stronghold and defensive New World frontier fort.

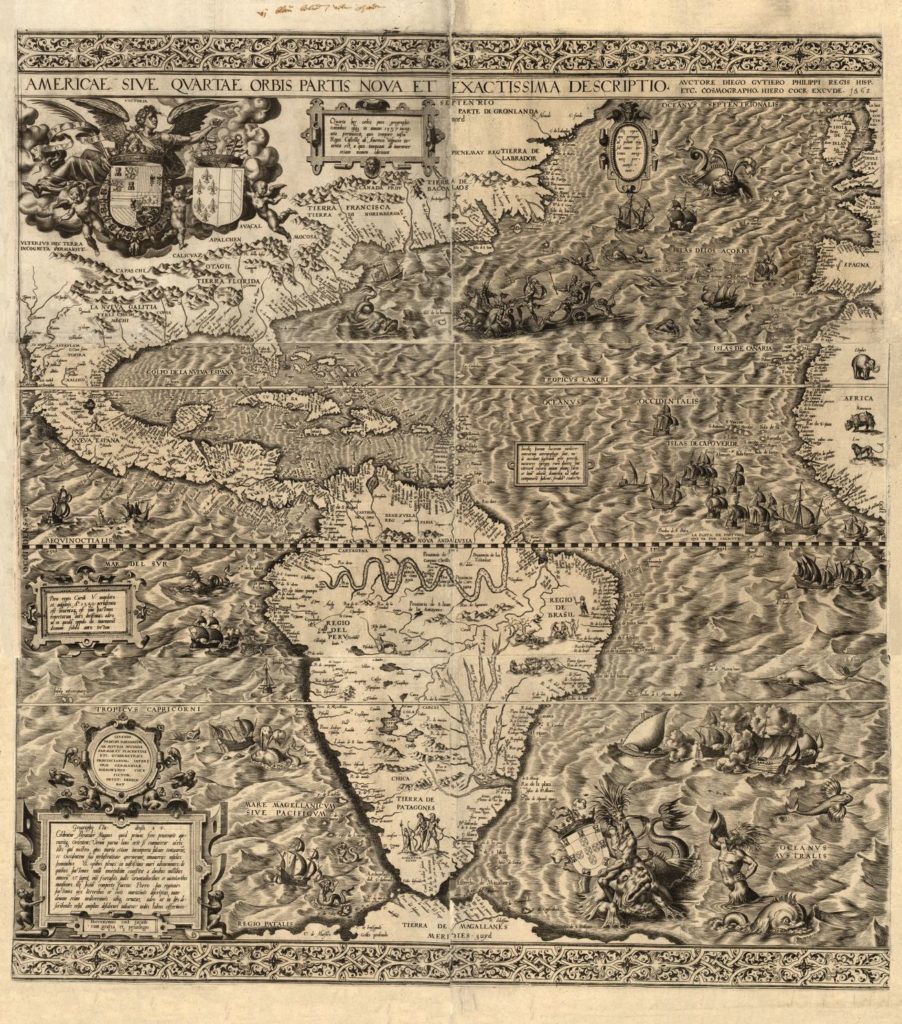

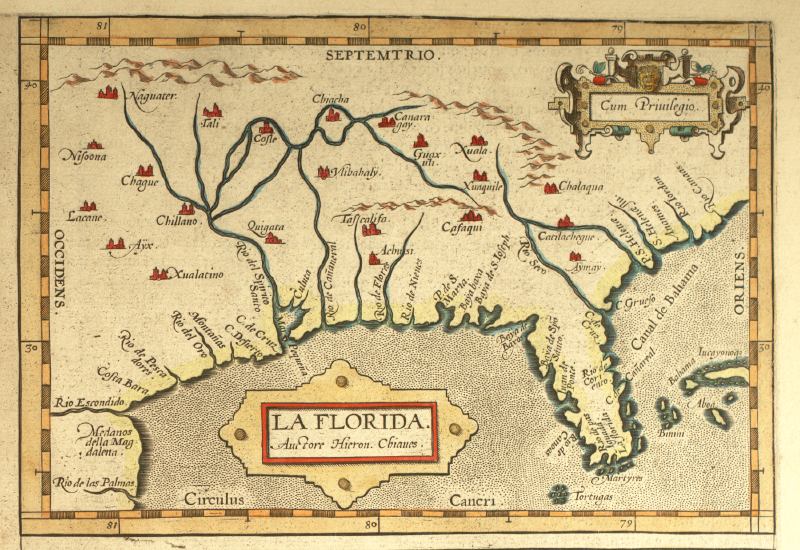

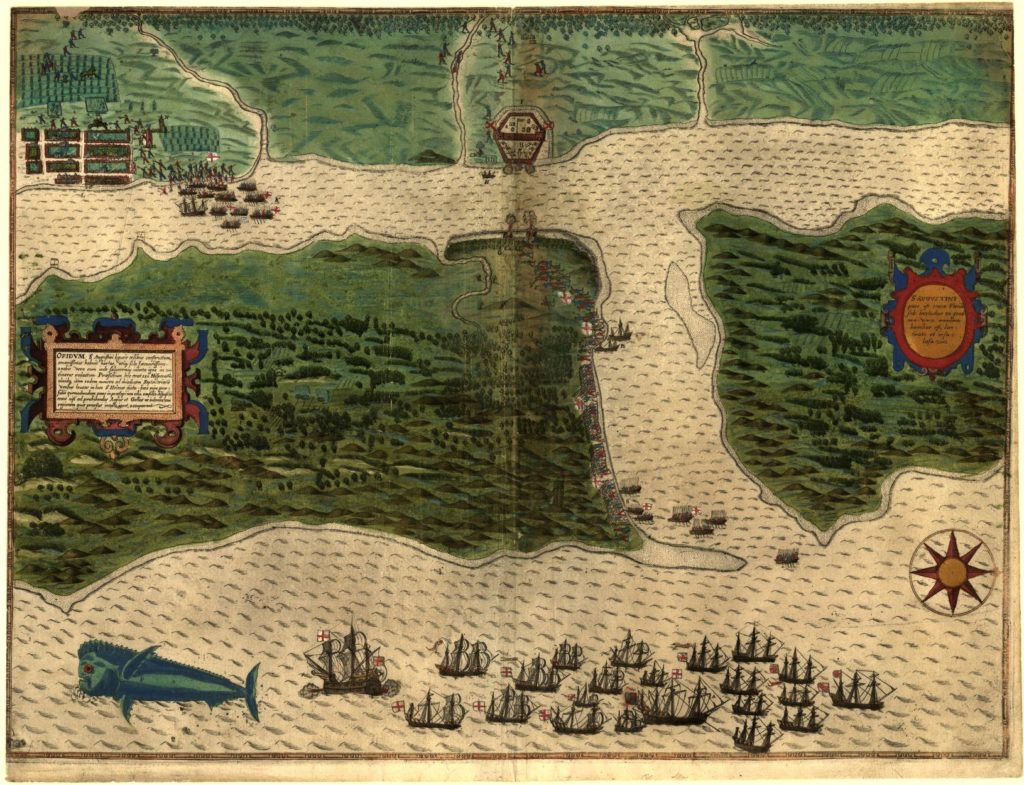

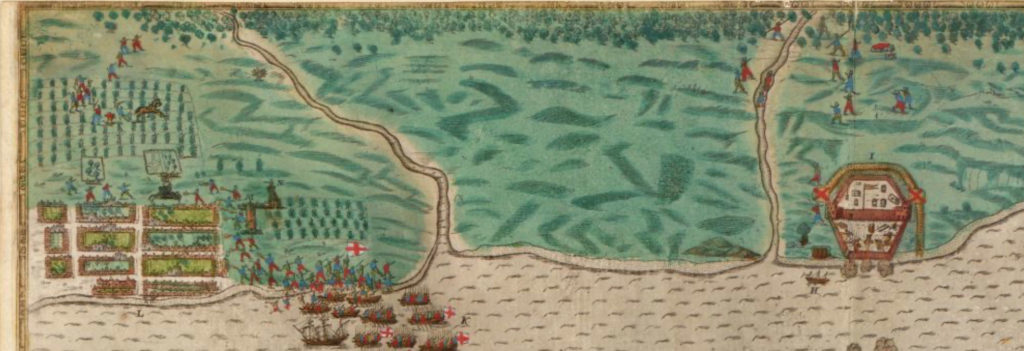

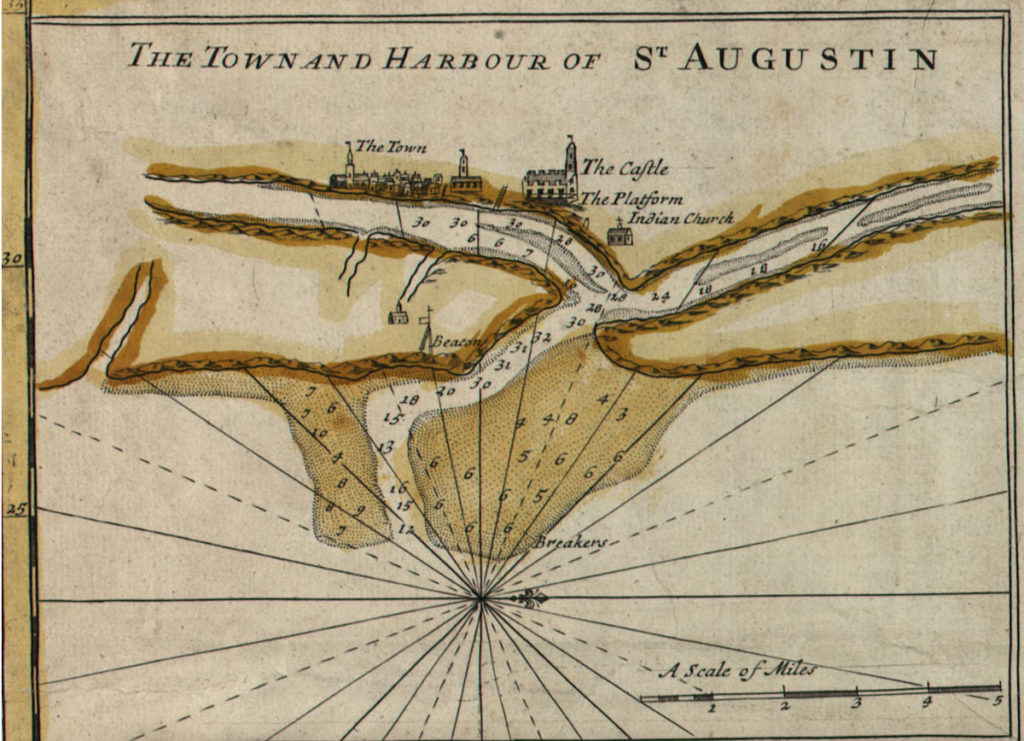

From the early days of the settlement, this spot held a defensive fort, though the earliest ones—nine in total—were wooden. [1] We know this from a significant map made by Baptisto Boazio, created to accompany a written account of Sir Francis Drake’s 1585 raiding expedition to attempt an upset of Spanish settlements in their new territories.

In September 1585 Drake set out with 29 vessels. He and his crew raided and captured Santiago (Cape Verde), Santo Domingo (modern-day Dominican Republic), Cartagena (modern-day Columbia), and St. Augustine. The illustrations made by Boazio, who either went on the voyage or used information provided by Sir Francis Drake or other sailors, are the first recorded views of each of these locations, and his drawing of St. Augustine is particularly notable as the first recorded view of a European settlement in North America.

His maps were printed to accompany the written account two sailors kept of that voyage. Captain Walter Bigges began the account and kept it until he died in Cartagena; Lieutenant Croftes continued it after Bigges’s death. [2]

Croftes described St. Augustine’s fort as still in progress, only three or four months old, “all built of timber, the walles being none other but whole mastes or bodies of trees set uppe right and close together in manner of a pale, without any ditch as yet made.”[3] Drake and his company burned the unfinished fort, and the town, to the ground.

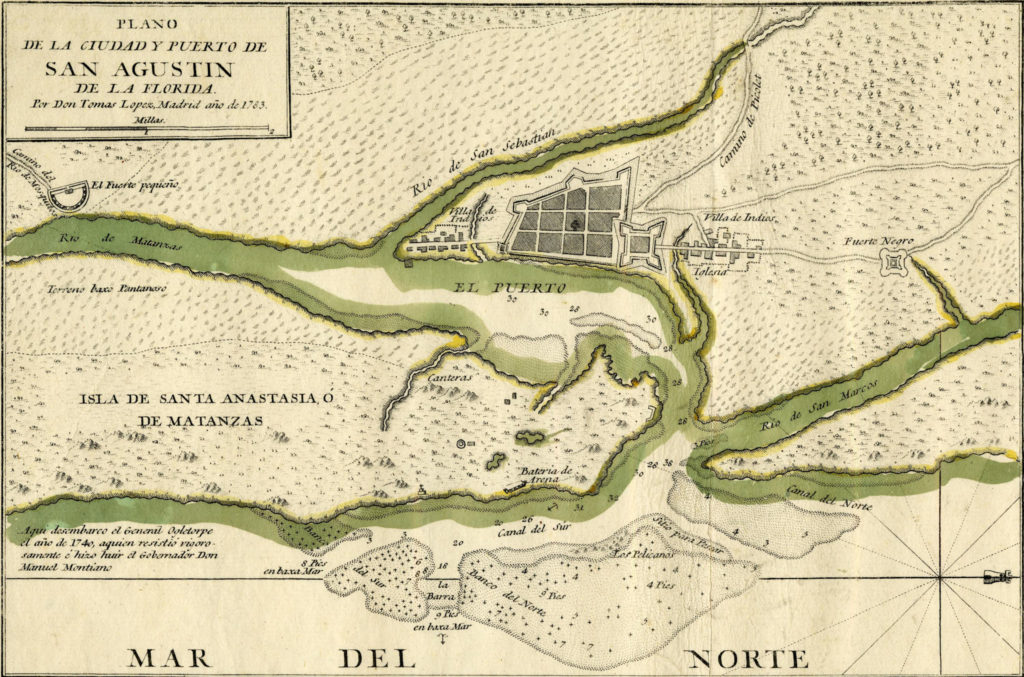

Though the fled survivors returned and rebuilt, much of the town was destroyed again just a few years later in a hurricane of 1599. Finally in 1672, the settlers began construction of a stone fort. Its first stage was finished in 1695 (the second stage ran from 1738–1756). [4]

Though the structure of the stone fort, made of native coquina, was post-medieval, it served in many ways as a medieval castle, a defense for the town around it and a place for St. Augustinians to shelter when under assault. In 1702, for example, when the British attacked, “about 1,500 soldiers and civilians were packed into the Castillo for 51 days!” [5]

The courtyard had three freshwater wells, the dry moat and the glacis offered protection from invasion, and both the inner and outer fortress had cannons and other types of munitions for fending off attackers.

A medieval coat of arms appears above both the ravelin (the v-shaped protective installation at the south end) and the sally port (the entrance into the south wall, reached by the drawbridge and protected by the ravelin). As in the city coat of arms that I discussed in Part One, the lions represent the Kingdom of León and the castles the Kingdom of Castile, the crown atop Spain, and the sheep and enclosing chain the medieval Order of the Golden Fleece.

Want to learn more about the fort from the comfort of your browser? Take the great virtual tour offered by NPS and hosted by the University of South Florida Libraries’ Center for Digital Heritage and Geospatial Information!

The City Gate and Walls

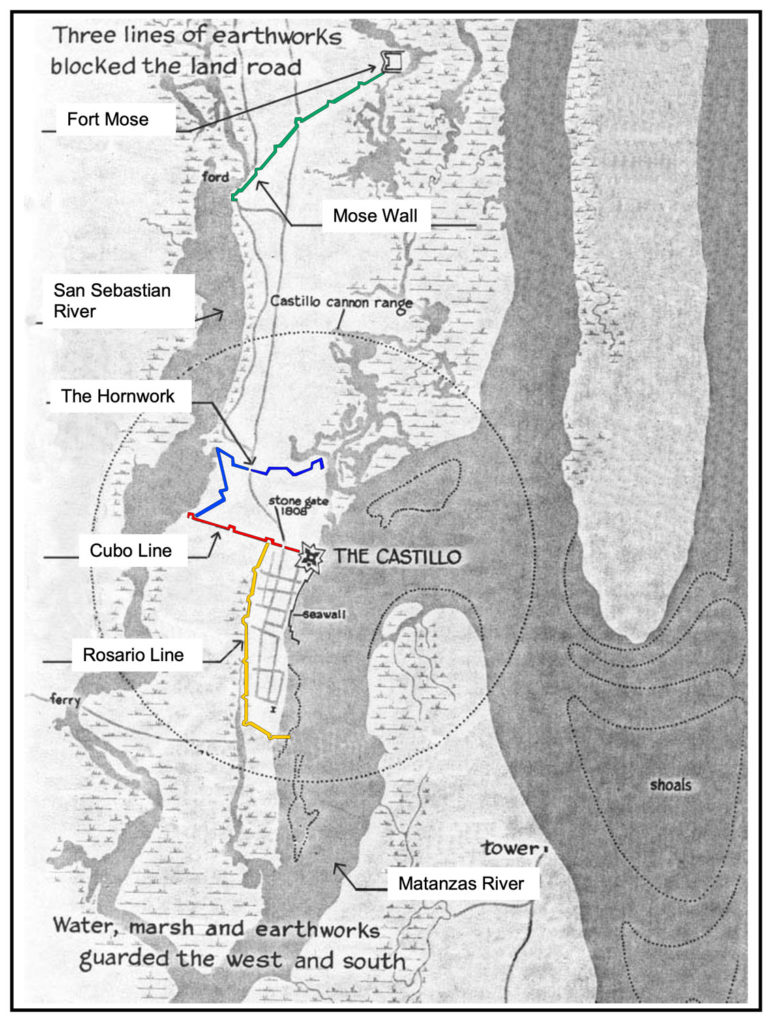

Running out from the western side of the Castillo, and reconstructed and visible today, is one of the city’s defensive walls. Like medieval cities, St. Augustine had not only a fortified stronghold but also a city gate and defensive walls. Most of these walls, or lines as the Spanish termed them, are reconstructions, though you will still feel very much like you’re walking through a medieval city when you see them (imagine, for example, the walls and gates of York, one of the most complete medieval walled cities in England.)

The gate and city walls of St. Augustine were not actually erected at its first settlement but in response to the British invasion of 1702. That experience prompted the city to enclose itself afterwards within medieval-style walls. The builders used native materials and constructed the lines as earthworks strengthened with local crushed coquina, or as walls of palm trunks.

St. Augustinians erected four protective lines: the Cubo Line (1704), the Hornabeque (or Hornwork) Line (1706), the Rosario Line (1718–19), and the Mose Wall (1762). [6] Each line also included redoubts (a term that comes from Classical Latin reducere “to lead back” and medieval Latin reductus “secret place” [7]), somewhat similar in concept to the turrets of the Roman-era Hadrian’s Wall in England.) You can visit a reconstructed redoubt, the Santo Domingo Redoubt, at the corner of Orange and Cordova Streets, near the VIC.

Colonial historian Dr. Susan R. Parker describes the construction of the lines:

“Out from the Castillo’s west side went strong earthworks in the style of medieval European walled cities to protect against siege warfare. This wall surrounded the city’s three landward sides and became the physical limits of the colonial city.

[…] Years later, about 1762, the northernmost wall was added to connect with the village of Fort Mose, the settlement established for enslaved persons who escaped from English colonies to Spanish Florida.

The lines were built of soil with coquina sometimes incorporated for strength. To raise the height of the wall, Spanish bayonets and prickly cactus were planted along its top. The walls required endless repair. The biggest threat to the wall were the hooves of free-ranging cattle that pawed away at the berms.

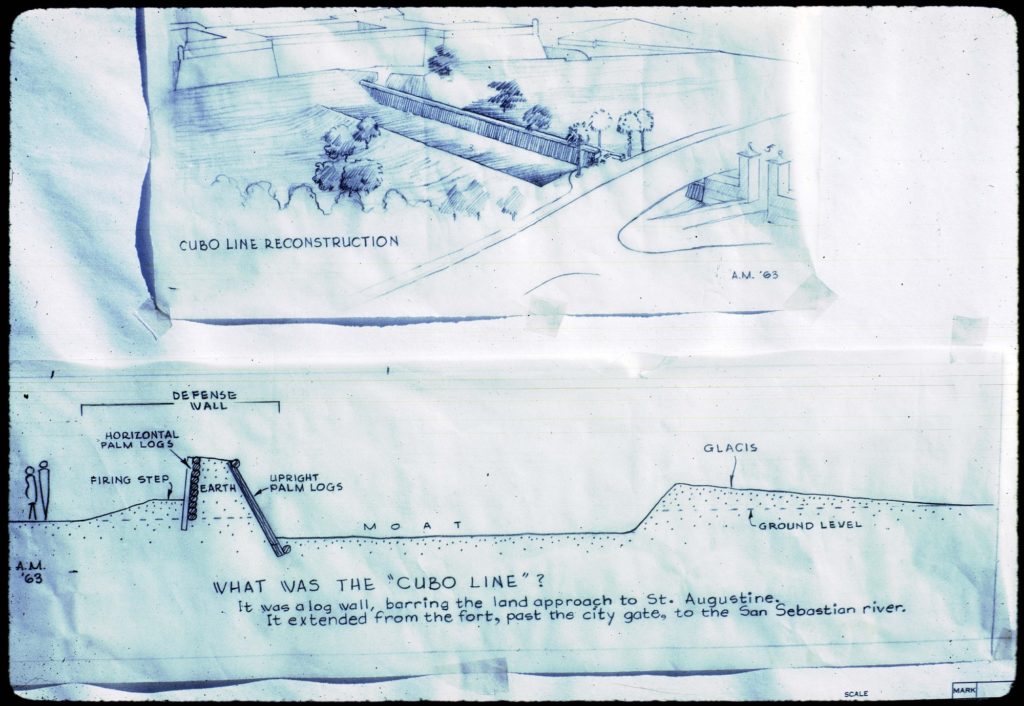

The reproduction Cubo Line that today crosses the grounds of the Castillo depicts a version of that barrier made of palm logs, built about 1808, a century after the first ‘Line.’ The City Gate was incorporated into this wall. The coquina pillars that stand today were built about the same time as the palm-log wall and replaced earlier entryways made of wood.” [8]

The Cubo line runs out of the west side of the fort, and the nineteenth-century version of palms was reconstructed in 1964 by the National Park Service. You can learn all about the materials and construction of this wall from NPS.

You can see more detail of the architecture of the Cubo line in the drawing below from the National Park Service.

The city gates are part of the Cubo line and lie a short distance from the western fort wall. The existing gates were reconstructed in 1808.

The city lines were, in fact, what inspired me to write these blogs on the medieval roots of St. Augustine. Wandering around the old city on one visit a few years ago, I came across a part of the city wall, running between buildings on the northwestern edge and not particularly marked or noted in any way. I stood there for a bit, playing my fingers gently over the coquina and mortar, and thinking about the medieval city walls of York (themselves much reconstructed, like St. Augustine’s), and medieval flint church walls I’d just spent a year examining in the eastern U.K.

These sudden medieval encounters in the everyday world are striking, connecting us with the past physically, and showing us links with our natural environment and its long history of inspiring the construction of protective barriers, homes, and places of worship. Builders in the U.K. from the Romans to the Elizabethans relied on flint, a stone arising from the Chalk Escarpment of eastern coastal (and some of inland) Britain. The masons who made York’s medieval stone walls quarried their materials from the Magnesian Limestone formation in that area. The masons of St. Augustine drew on the native coquina, a limestone formed naturally of compressed and partially-dissolved shells of the coquina clam donax variabilis. St. Augustine’s limestone was quarried from nearby Anastasia Island.

The Historic City

While only a few reconstructed sections of the lines exist today, you can still enter the historic district of St. Augustine through its city gates, and from there step into a colonial Spanish town. Most of the city’s historic buildings are restored or reconstructed from its colonial era (First Spanish Period, 1565–1763; British Period, 1763–83; Second Spanish Period, 1783–1821) and early American period (after 1821). This lack of surviving older structures has much to do with St. Augustine’s military past: as a key outpost, the city weathered a number of massive attacks on its fort and settlement, such as Drake’s destruction of it in 1585 or the 1702 British attack that left the city burned to the ground again. Both post-Civil War Reconstruction and Henry Flagler’s investment and overhaul of the city in the late-nineteenth century meant the demolishing of many of the older buildings and construction of new ones.

The 1971 Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board’s Guidebook notes of the period of demolishment that “The old and storied inevitably gave way to the then new and modern. Many old houses and the remaining sections of the defense lines were uprooted to make way for new buildings. In those days these changes were hailed as a great improvement. Construction wasn’t the only enemy St. Augustine had, however; fire did its share of damage. In 1887 flames swept the Cathedral and much of the north block of the plaza. In 1914 a disastrous fire wiped out many of the buildings in the older section of the city between the city gates and the plaza.” [9] In the 1930s, though, St. Augustine became the focus of historic restoration, with organizing efforts to protect the historic district and return the city to its first Spanish period appearance. This Guidebook contains fascinating information from its time about the history and reconstruction of many of the buildings you can visit today.

Careful attention to the historical restoration process has resulted in a city that still reflects clearly its Spanish heritage. Albert Manucy in his book Sixteenth-Century St. Augustine writes,

“Although none of the first colonial houses of St. Augustine remain, it is clear from the later survivors that they are related to the folk architecture of northern Spain, the home of Pedro Menéndez, the town’s founder. Today in Oviedo and Santander Provinces one can see masonry houses, often with overhead balconies, front the streets. House lots are fenced to serve as corrals and stables. And in the town of Treceño there are houses with roomy ground-floor loggias, open to the yard through an arcade of two or three arches. These same styles can be seen in St. Augustine, and they have been there a long time.” [10]

This “folk architecture” itself was influenced by the medieval era (unfortunately I don’t have space to delve into this topic here.)

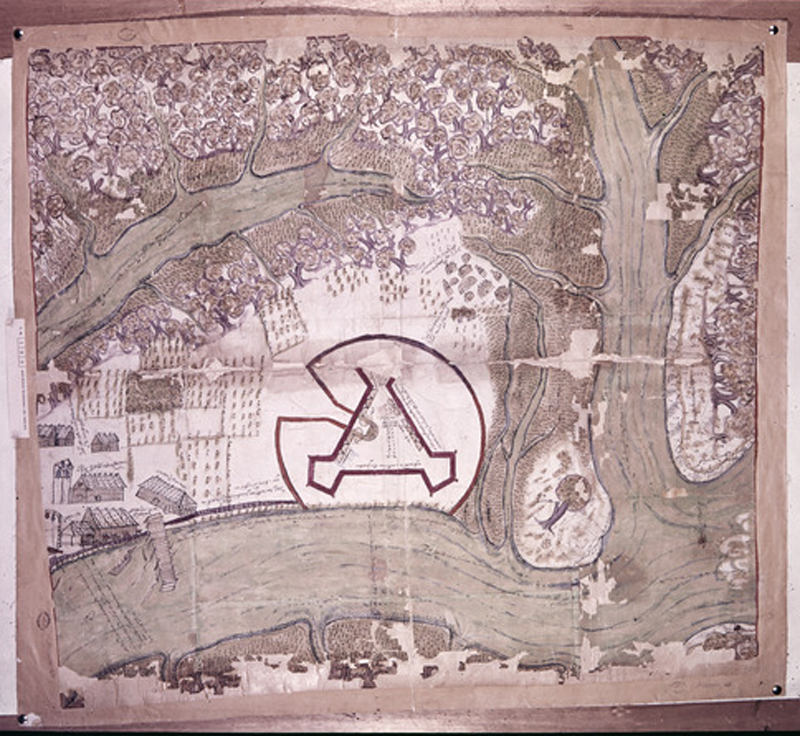

You can still see the city’s beginnings, though, in its layout and street plan, which has changed very little from its first formal layout in 1597. When Menendez and his group landed in the area in 1565, they first settled in cacique Seloy’s Timucuan village (the present-day Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park). After 9 months Menéndez and the settlers moved to Anastasia Island, then in 1572 moved back across the bay to the present site of St. Augustine and laid out their town. This town reflects a key feature of Classical and medieval architecture and a hallmark of Spanish urban planning: a plaza (though nascent) on the northern end of the town. To see what that town looked like, let’s step back Boazio’s 1589 map.

The legend for the map describes the fourteen-year-old settlement in this way:

“Opidum S. Augustini ligneis aedibus constructum, amoenissimos habuit hortos, utique solo faecundissimo”

(The town of St. Augustine, built of wooden houses, had most pleasant gardens, of course on a most fertile soil”).

Boazio’s engraving, showing Drake’s attack on the town, shows these houses and gardens, laid out to the south of the sixteenth-century fort.

Croftes describes the scene further, as the troop moved from the coast up the river:

“we might discerne on the other side of the river over against us, a fort [San Juan], which newly had bene built by the Spaniards, and some mile or there about above the fort, was a litle town or village without walls, built of wooden houses, as this Plot [Boazio’s map] here doth plainlie shew.” [11]

Boazio’s map shows a number of buildings, likely with palm- or palmetto-thatched roofs, and well-laid-out gardens. Archeological excavations have also confirmed the presence of a church, Nuestra Senora de Los Remedios (Our Lady of Remedies), since 1572 (St. Augustine, in fact, was America’s first Catholic parish). Records have confirmed the presence of a governor’s house near the water.

The open area surrounded by the church, town hall, and watchtower form a rough sort of early plaza, a plaza that was formalized shortly after by the next governor and that still exists today as the Plaza de la Constitucion, in the middle of the colonial halves of the city.

In their book, Ancient Origins of the Mexican Plaza, Logan Wagner, Hal Box, and Susan Kline Morehead discuss the importance of a central gathering place in city planning the world over, from ancient times to present. They note that “Plazas, or communal open spaces of some kind, have been at the core of every town and city in every culture on every continent.” [12] In the Western European world, the Greeks and Romans engaged in urban planning practices that provided for both sacred space (the Parthenon and Acropolis for Greeks, the Forum and Templum for Romans) and commercial and civic space (the market square).

About the development of urban planning in the Spanish New World, Wagner et al. write,

“The origins of Spanish urban layouts in the New World can perhaps be traced to urban design principles established by the celebrated Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century BCE; or possibly to ideas being discussed by the urban designers of the Italian Renaissance, especially Alberti; or even to the French bastides of the thirteenth century; or to the need to have a town layout that was expedient for military actions. The official policy of the Spanish Crown to design new towns in a grid or ‘checkerboard square’ pattern emanating from a central open space or plaza did not become official until well into the latter quarter of the first century of Spanish colonization, when grid layouts were finally made official in 1573 during the reign of Phillip II. The document in which these instructions were decreed is known as ‘The Laws of the Indies.’”

The authors note that, though the Laws were explicit and highly prescribed, in reality, settlements typically accommodated both existing native settlements and topographic features. [13]

When the Spanish settlers returned after Drake and his company ended their raiding and headed north to Virginia, they had to rebuild, and put up a new wooden fort as well. Carmelite lay brother Andrés de San Miguel described the refounded settlement in 1595 as being a little over a mile long (“one-half league”), with plenty of water to drink and various crops. Of the buildings he writes, “All of the walls of the houses are of wood and the roofs of palm and the more important ones of plank. The fortress [is] made of wood backed by a rampart.” Further, “The Spaniards make the walls of their houses out of this wood of cypress (sauino) because the part of it that is in the ground does not rot.” [14] The town that Fray Andrés saw was that depicted in a map of ca. 1593, the “de Mestas map,” possibly created by Hernando de Mestas, St. Augustine emissary to Spain.

When the new governor of La Florida, Gonzalo Méndez de Canzo, arrived to St. Augustine in 1597, he carried out Phillip II’s new Laws of the Indies and overhauled the layout of the city to that effect, including establishing a marketplace in the plaza. He also moved the governor’s house westward, to the back of the plaza, “probably to have the location of the governor’s office comply with Spanish ordinances that major buildings face the main square (plaza).” [15] The Laws of the Indies blended Classical and medieval urban planning traditions with early modern sensibilities and responded to both the practical requirements of Spanish colonial outposts and the desire for a fresh, new, planned aesthetic for a new age and a New World.

Méndez de Canzo’s layout for St. Augustine was the one that stuck for the city. Though the town was severely damaged in 1599, first by a fire that burned down the Franciscan monastery at the south end of town, and then by a hurricane that swept away most of the houses and killed many inhabitants, and burned down by the British in 1702, St. Augustinians kept rebuilding on the town layout. [16]

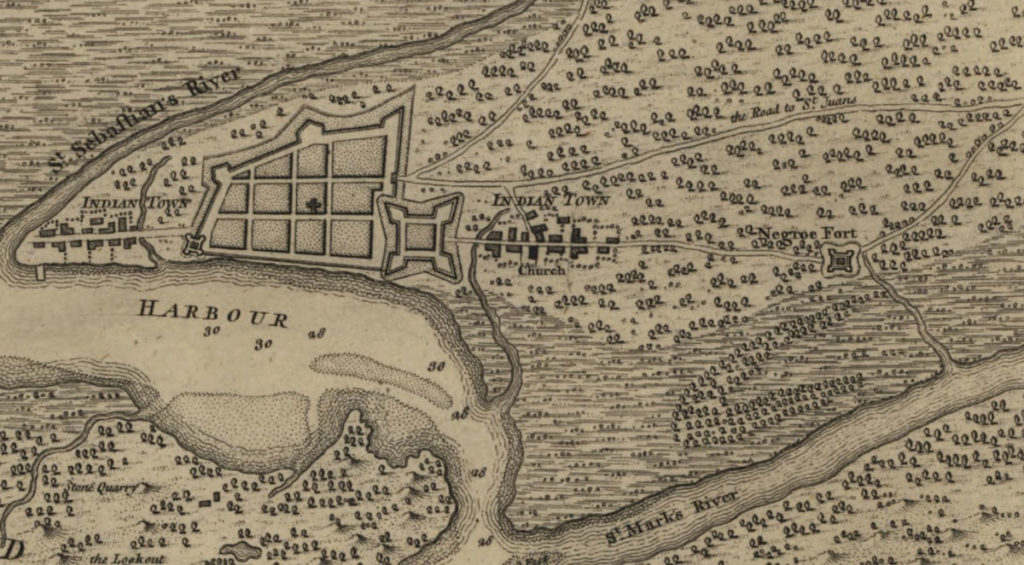

A 1711 map shows the new growth of the town, with the settlement and fort still somewhat distant from each other.

By the time the British took over St. Augustine as part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, though, the town had expanded northward and reached the area of the castillo. (From 1763-1783 Saint Augustine was a British territory, East Florida, and was its capital. In 1783 Britain gave this territory back to Spain, and in 1819 Spain gave it to the United States. )

The church (not the present cathedral) is denoted in the plaza area by a cross.

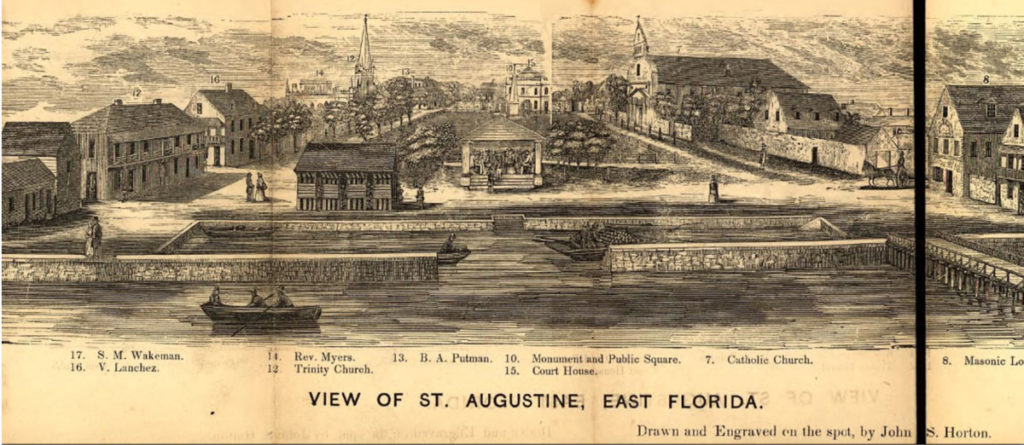

This 1855 view from the harbor shows how well-developed the plaza had become since Mendez laid it out in 1597.

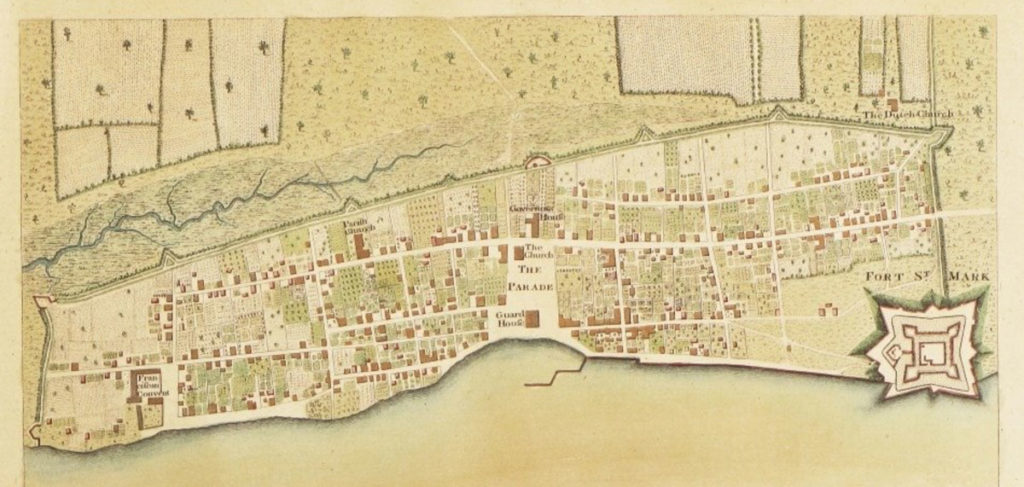

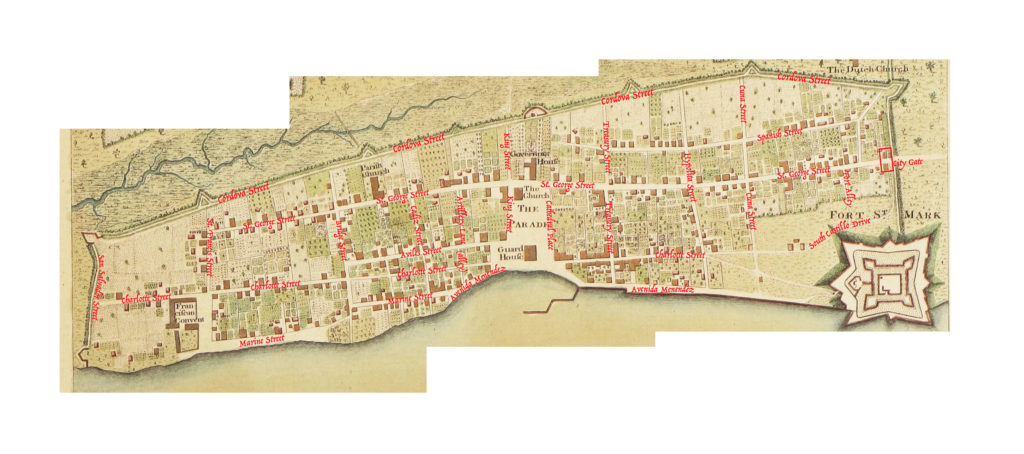

Thomas Jeffrys’s 1769 map (above) shows that by the mid-eighteenth century, St. Augustine had grown to join with the fort, fully achieving de Canzo’s sixteenth-century plan. The Lines encompass the town, with the plaza (here formally noted as “The Parade”) at the center. This plaza was bounded by the Guard House at the harbor to the east, the church at the southwest corner, and the Governor’s House at the west end. The houses still had the “pleasant gardens” and orchards of the settlement’s earlier days. The fort appears at the northeast corner, with the Lines and their redoubts marked. The City Gate appears directly to the west of the fort, with present-day St. George Street running through the gates’ entrance into the walled city.

In the overlay I’ve done below, you can see how precisely the modern historic district maps onto Jeffrys’s eighteenth-centrury engraving of the town:

Remarkably, between this 1769 map and one of today, only a few of the streets have been swallowed up by development.

Walking through the streets of historic St. Augustine today is a treat for any lover of history. The careful reconstruction, street cobbles, balconies, and low buildings all create an atmosphere that is both medieval, European, and also distinctly Floridian. To see photos of more of the colonial buildings, check out this site.

The city claims to have currently “thirty-six buildings of colonial origin and another forty that are reconstructed models of colonial buildings.” Why not take a break from Disney World and visit something of Florida’s medieval history instead? You won’t regret it.

How can you learn more?

Get involved in St. Augustine’s archaeology program as a volunteer!

Read more about the history of St. Augustine from the Florida Museum at the University of Florida

Check out this guide: St. Augustine Under Three Flags: Tourist Guide and History

Footnotes

[1] Albert Manucy, Sixteenth-Century St. Augustine: The People and Their Homes (Gainesville: U P of Florida, 1997), pg. 36.

[2] It was first published in Latin and French in 1588 and then in English in 1589 (in two different editions) as A Summarie and True Discourse of Sir Frances Drakes West Indian Voyage (S.T.C. 3056 and 3057). Side note for lovers of book history: the second English edition of 1589 directs readers where to insert the maps, sold separately, into their copy of the book, and each of the four town maps has additional “textual keys, separately printed on broadside sheets intended to be cut and pasted at the bottoms of the four town maps.”

Mary Frear Keeler notes of the text and maps that “Richard Hakluyt reprinted the Summarie in his Principal Navigations, 3 vols. (London, 1598–1600); 12 vols. (Glasgow, 1903–1905). The engraved maps, printed with texts in three languages to correspond with the editions of the Summarie, are clearly associated with the publication of that narrative, and are referred to on the title page of the Ward edition (1589). A complete set of the Boazio maps is bound with the British Library’s copy of the Summarie (Field edition), numbered G. 6509” (“The Boazio Maps of 1585–86,” Terrae Incognitae 10 (1978): 71–80, at pg. 71).

[3] Croftes, A svmmarie and trve discovrse of Sir Frances Drakes West Indian voyage (London, 1589), p. 32.

[4] “La Ciudad de San Agustín: A European Fighting Presidio in Eighteenth-Century ‘La Florida’,” in Historical Archaeology 38.3, Presidios of the North American Spanish Borderlands (2004): 33-46.

[5] “Courtyard” information card, USF virtual tour of the Castillo.

[6] “La Ciudad de San Agustín,” pp.33-46.

[7] “Redoubt (n.),” Oxford English Dictionary online.

[8] Susan R. Parker, “Wall surrounded St. Augustine in 1700s,” in the St. Augustine Record (Jan 2019).

[9] Pg.4

[10] Pg 5

[11] A Summarie and True Discourse of Sir Frances Drakes West Indian Voyage (London, 1589), pp.30–1.

[12] Logan Wagner et al., Ancient Origins of the Mexican Plaza: From Primordial Sea to Public Place (Austin: U of Texas P, 2013), pg.41.

[13] Wagner et al, pg.46.

[14] Fray Andrés de San Miguel, An Early Florida Adventure Story, trans. John H. Hann (Gainesville: U P of Florida, 2000), pp.76-7.

[15] Susan Richbourg Parker, “St. Augustine in the Seventeenth-Century: Capital of La Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 92.3 (2014): 554–76, pg.556.

[16] Parker, “St. Augustine in the Seventeenth-Century,” pg.557.