Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about Margery Kempe. In fact, I’ve thought about little else the last few months, since her Book was the focus of my most recent chapter in a dissertation that examines women’s desire in Medieval English texts – and The Book of Margery Kempe has a lot to say on the subject. Mostly, I’ve been thinking about how Margery thinks about sex and why she thinks about sex the way she does.[1]

I’ve also been thinking a lot about teaching – lately, about teaching The Book of Margery Kempe. I love teaching, and I love thinking about literature courses I’d love to teach. As a scholar whose research focuses on representations of women, I look forward to teaching a course devoted to medieval women one day. The reading list would obviously include works written by women during the Middle Ages, and we have few examples, especially in English. I will be teaching The Book of Margery Kempe, and when I do, I want to do it well, so I was wary of the weariness I’ve experienced while reading it.

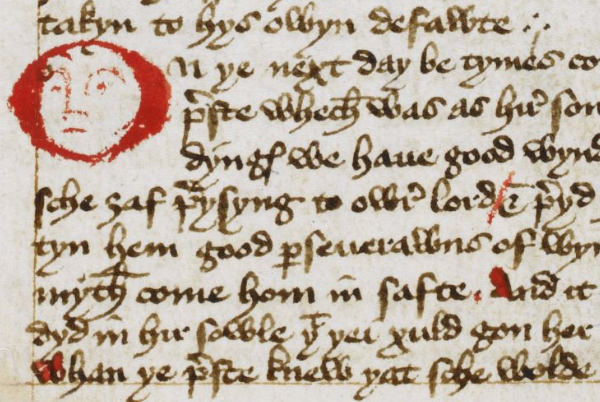

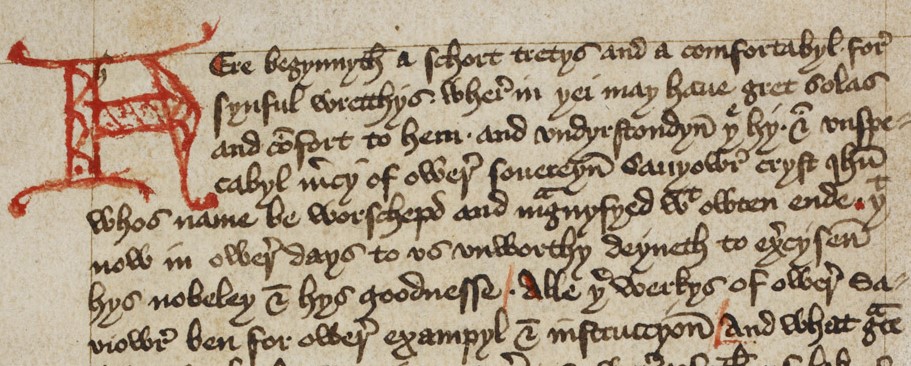

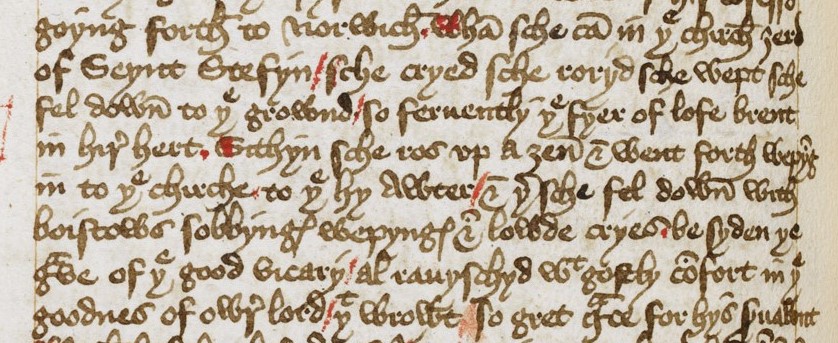

Much like Margery, I have a confession to make: I have never been especially fond of her Book. But I have also never failed to recognize its value. As one of the only known Medieval English works written by a woman and often considered the first autobiography written in English, her Book is extremely precious, in part, because it provides us insight into a medieval woman’s life that is dictated in her own voice if not written by her own hand. It survives in a single manuscript, discovered in 1934 and dated to approximately 1440. When I had the opportunity to see the manuscript on display at the British Library, I revered the object behind the glass because I understand the worth of its words. When I re-read the narrative recently, I felt exhausted, often frustrated that so many pages remained until its end.

The Book is long; it is neither chronological nor linear. Sometimes it seems repetitive to the point of redundancy. But it is salacious, tender, even occasionally funny. It is also profoundly sad.

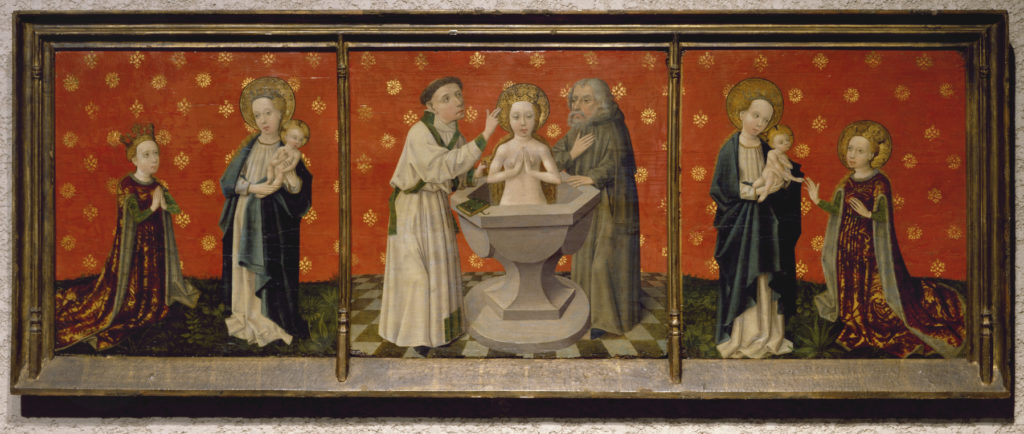

Best known for her spectacular physio-emotional displays that so often occurred in public and provoked concern, Margery Kempe has always been a controversial figure as a woman mystic. Her Book is, in many ways, a memoir that recounts her spiritual journey, tracing the origin of her mystical experiences to the birth of her first child at age twenty and the self-described madness that ensued. It is only when Christ appears to her, seated next to her on her bed, that Margery’s sanity returns. In many of her visions, Margery’s interactions with Christ exhibit sexual undertones; indeed, some visions are overtly sexual. While erotic language and metaphors were not uncommon in medieval mystical writing, especially those involving women mystics, Margery’s visions are unusual in that they imply sexual activity with Christ himself.

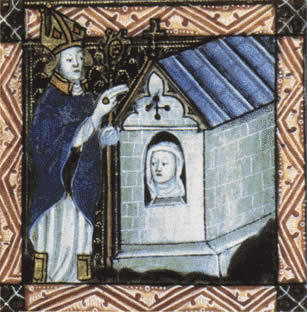

Margery describes herself as illiterate in her preface, but this does not mean that she was unlearned. It does, however, mean that she required a scribe. Her narrative was mediated by two male scribes, which complicates her status as an author, an already fraught term in the Middle Ages on par with autobiography, since the genre did not yet technically exist. She was a wife, the mother of fourteen children, and inordinately mobile, traveling for extended periods of time on pilgrimage to holy sites, which took her away from her husband and children. Unlike other religious women, Margery was neither virginal nor cloistered. She preferred to be on the move, and traveling was one of the ways she was able to avoid unwanted sex.

Here, I pause to provide a content warning and meditate for a few moments on what that means. The discussion that follows involves sexual violence, a topic tied to gender and power, which are, in turn, topics pertinent to any discussion of literature. Because I am constantly working at the intersections of gender, sex, and violence, I think a lot about how to prepare my students to successfully navigate discussions of sexual violence, knowing very well that it may be personally relevant for them. After all, sexual assault is rampant in the United States, with one in three women experiencing sexual violence in their lifetime. One in five women experiences sexual assault while in college, and they are most vulnerable during their first year. While men experience sexual violence at a significantly lower rate than women, those who do are likely to have those experiences prior to or during college. Sexual violence remains an omnipresent part of our cultural conversation, even when we’re not talking about it explicitly and we should be.

A content warning is a standard feature of my syllabus. I believe that my students should be aware that they are likely to encounter sexual violence in our reading. It does not encourage them to opt out of reading assignments or evade challenging discussions; instead, the contextualization enables them to wrestle meaningfully with the material in the way that best fits their needs and fulfills our learning goals. If they are prepared for the content, they may be able to avoid unnecessary triggering, a term that gets tossed around far too frequently by folks who are far too flippant about rape culture and has been distorted through stigmatization. A “trigger” warning suggests an inevitable, uncontrollable reaction, whereas a “content” warning cues students to prepare accordingly. Semantics aside, we need to be proactive when teaching The Book of Margery Kempe.

Following the spiritual revelation that sparks her mysticism, Margery renounces sexual activity. She commits herself to chastity and begs her husband to live chastely with her – that is, to allow her to abstain from sex, to not force her to have sex with him. He refuses. For years, Margery endures marital rape.

I realized recently that my ability to properly empathize with her situation had been impaired by my own biases about the narrative’s style.

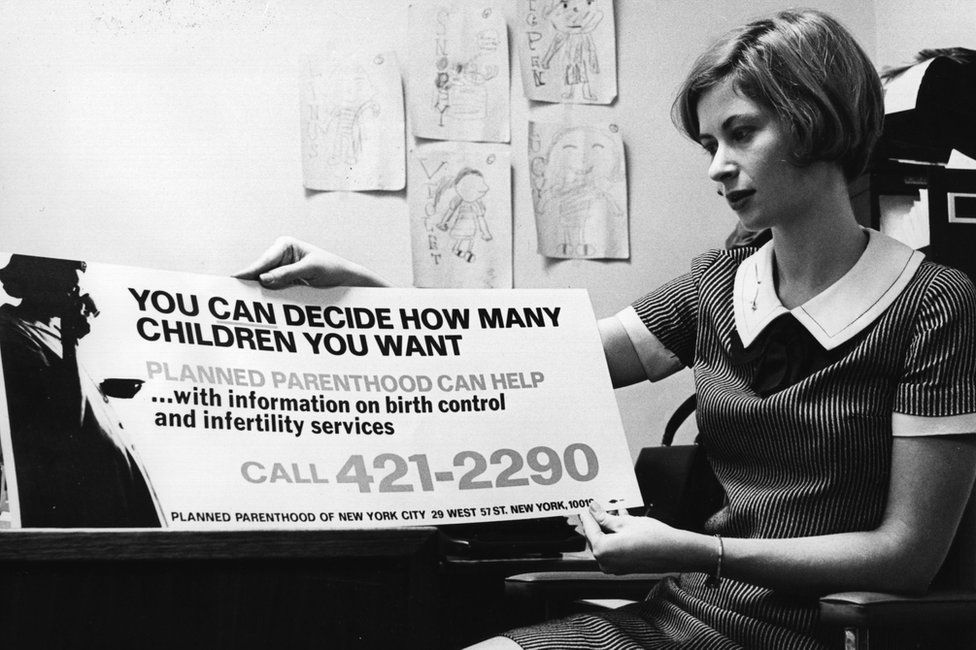

I was reading Rebecca Solnit’s Men Explain Things to Me, which unravels the relationship between speech and gendered violence. There is a point at which Solnit refers to the 1940s and 1950s, which I always think of as the decades from which Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique emerged and exposed the tragic irony of America’s failure to understand how women could possibly be so miserable as housewives when they couldn’t get a credit card without a husband and couldn’t get birth control, period. While contraception was legalized in 1965, women could be legally raped by their husbands in the United States until 1993.

Solnit simply refers to the dates for the purposes of prefacing an anecdote about a man she knew who, during that time, “took a job on the other side of the country without informing his wife that she was moving or inviting her to participate in the decision.” She writes, “Her life was not hers to determine. It was his.”[2] Margery immediately came to mind.

During the medieval period and well beyond, women ceased to occupy a separate existence from their husbands when they married. A wife did not retain a will of her own; her will was legally subsumed by her husband’s. On this subject, I am well versed. But for some reason, Solnit’s exemplar resonated with me more acutely than Margery’s experience previously had. Certainly, the rather arduous experience of reading her Book had engendered more impatience than sympathy, but I had failed to really feel the extent of her suffering, and for that I felt deeply guilty.

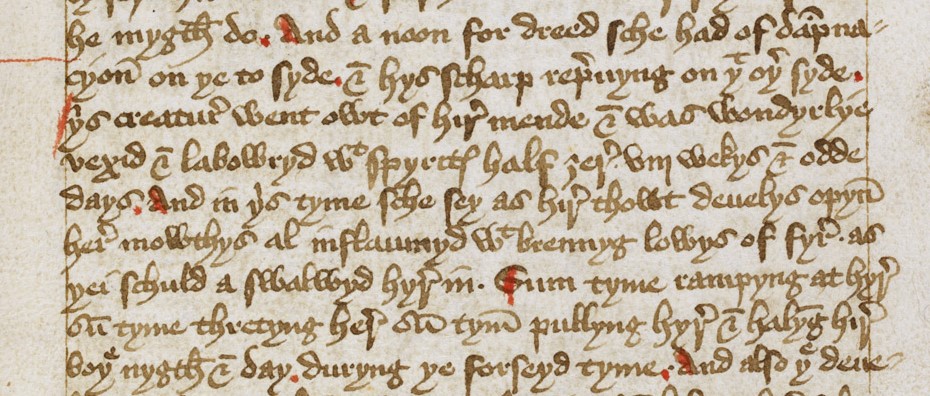

I returned to the passage where Margery describes her sexual loathing and her subjection to repeated rape:

“And aftyr this tyme sche had nevyr desyr to komown fleschly wyth hyre husbonde, for the dette of matrimony was so abhominabyl to hir that sche had levar, hir thowt, etyn or drynkyn the wose, the mukke in the chanel, than to consentyn to any fleschly comownyng saf only for obedyens. And so sche seyd to hir husbond, ‘I may not deny yow my body, but the lofe of myn hert and myn affeccyon is drawyn fro alle erdly creaturys and sett only in God.’ He wold have hys wylle, and sche obeyd wyth greet wepyng and sorwyng for that sche mygth not levyn chast.”[3]

“And after this time, she never had the desire to have sex with her husband, for the debt of matrimony was so abominable to her that she would rather, she thought, eat or drink the ooze, the muck in the channel, than to consent to any fleshly commoning, except in obedience. And so she said to her husband, ‘I may not deny you my body, but the love of my heart and my affection is drawn from all earthly creatures and set only in God.’ He would have his will, and she obeyed with great weeping and sorrowing because she could not live chastely.”

I haven’t stopped thinking about those particular tears. Or my misgivings about her memoir.

With more than 500 years between us, it can be challenging at times to make tangible how extraordinarily different and difficult medieval women’s lives must have been – and yet, sexual violence remains so prominent a presence in our daily lives that content warnings appear in my syllabi.

I see Margery Kempe so much more clearly now, the medieval woman writer who is a singular survivor just like her Book. And I want my students to be prepared to see her as I do: individual and immortal.

Emily McLemore

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of English

University of Notre Dame

[1] While it is obviously standard practice to refer to an individual by their surname, this practice also presumes that one’s surname represents the individual to whom it refers. Perhaps less obvious are the problems with identifying medieval women by their surnames when those very names are indicative of the subsuming of their identities by their husbands in conjunction with coverture, the legal doctrine that removed a woman’s rights and separate existence in marriage. Margery Kempe’s surname, for all intents and purposes, is tied to her erasure as a woman. I have chosen to refer to her as Margery to center her as an individual and retroactively counteract the masculine authority that governed her existence.

[2] Rebecca Solnit, Men Explain Things to Me (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2015), 59-60.

[3] The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Lynn Staley (Kalamazoo: The Medieval Institute, 1996), 26.