Like other scholars in the field, I recently wrote about the use of medieval symbolism in the white nationalist movement involved in the January 6th attack on the US Capitol, which focused on how they mobilize narratives of white supremacy and an imaginary “pure white” medieval period in European history to recruit members to their cause.

Then, to my horror, I recently discovered that indeed my own work has been appropriated by white nationalist rhetoric. My blog on Woden’s characterization as an ancestral chief in certain early medieval sources was both cited and misrepresented in the service of white supremacy in another blog titled “How ‘Ignorant’ Pagans Deified A Real-Life Wodan Into Their Ancestral Anglo-Saxon Warrior God ‘Odin’.” This blog was initially published by the website ChristiansForTruth (1/20/2021), later reappearing on European Union Times (1/22/2021) and Ancient Patriarchs (2/5/2021), and it promotes specifically Christian white nationalist propaganda.

My original blog, “Woden: Allfather of the English,” was written in 2015, during the early years of my PhD studies at the University of Notre Dame, when I was much less sensitive (or aware) of the ways in which this type of work was being used by white supremacists. This lack of awareness underscores my own white privilege and highlights my ignorance with respect to this issue, especially considering how medievalists of color have been actively calling out these harmful appropriations. For this reason, and in light of recent events, I feel that it is absolutely imperative that I respond directly, clarify my own position, and reject the noxious white supremacist claims embedded in this dishonest framing and mischaracterization of my work.

There are so many problems with ChristianForTruth’s blog, it is hard to know where to begin. The blog laments how “European paganism is very popular among many White Nationalists” and proceeds to try and reclaim their allegiance within a Christianized version of white supremacy. It gets worse from there. The blog erroneously asserts that “White Europeans migrated up into Europe from the Near East” in its effort to define Europe as uniformly white, and adds that “At the time of Christ, the Near East — including Anatolia (modern Turkey) and Judea — were inhabited largely by White people — extending across most of the northern coast of Africa.” As with arguments made by certain philologists and Egyptologists in the past, this narrative supports the white surpremacist notion that ancient Egypt was specifically “white” in a rhetorical move designed to strip Africa of one of its best known and most prominent, premodern civilizations.

Their agenda is laid bare when the anonymous authors that comprise the mysterious “CFT Team” contend that “Christianity has been a ‘European’ religion from its foundations — the apostle Paul sent his epistles to White European peoples” as they complain that “We know from history that most of this area was eventually overrun by Arabs — who now occupy — and live on top of — much of this former White homeland — the literal cradle of our civilization.” The use of “our” here, to refer to white people specifically, is another indicator of the blog’s rhetorical aims, which concern identifying Christianity as natively European and misrepresenting both medieval Europe and the ancient Mediterranean world as homogeneously white.

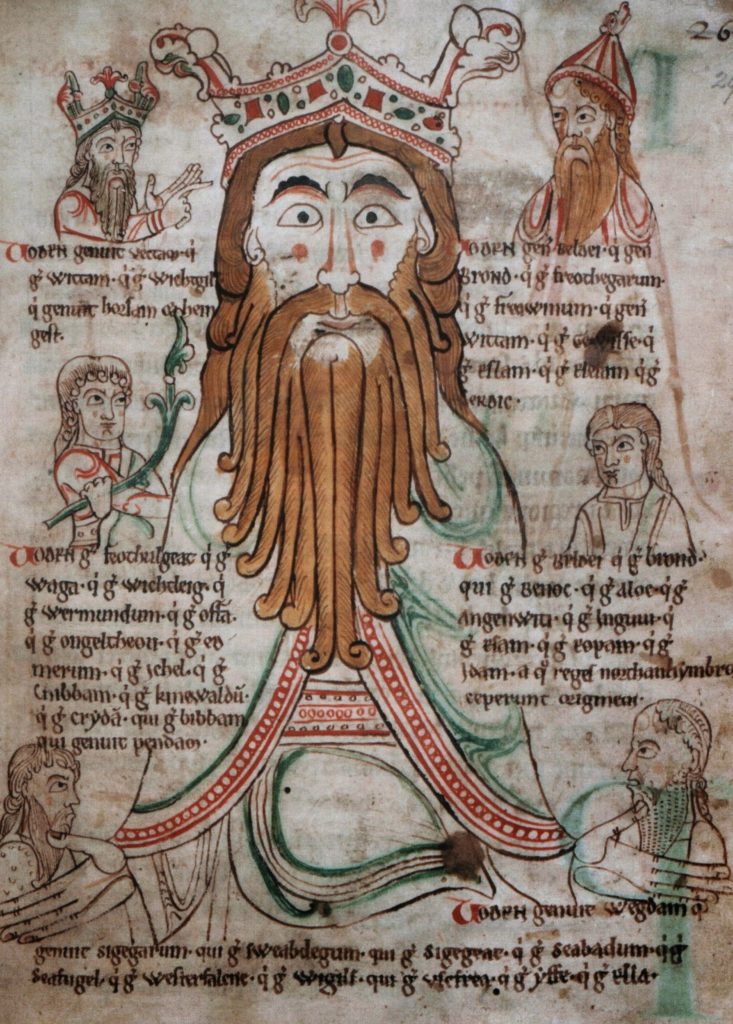

At the very end of the blog, the CFT Team further reveals their hand by placing Woden directly within a Christian worldview and alleging ridiculous genealogical connections. The blog concludes by stating that “Woden/Odin was a Saxon, a Goth, a Scythian, an Israelite — but he wasn’t God,” thereby fusing their theological argument for Christian superiority within their ethnocentric argument for white supremacy.

Although ChristianForTruth’s post reproduces almost my entire blog, it clearly was not read very closely. The CFT Team states that when it comes to regarding Woden as a god: “There is only one small problem with this fanciful narrative — Woden was a real man — a historically-documented ancestral chieftain — that pagans long ago turned into a god — and began to worship as a god out of sheer ignorance, according to Medieval historian Richard Fahey [my PhD is in English].”

This is not at all what I argued in 2015, and these claims attributed to me are in actuality the arguments of the CFT Team alone (seemingly drawn from my discussion of the 10th century historian Æthelweard‘s writing). They do not in any way represent my opinions or beliefs on the subject. In my initial blog, I make no judgment as to whether to regard Woden (or Odin) as principally a god or an ancestor, and I certainly do not consider the deification of Woden a matter of “sheer ignorance” on the part of pre-Christian peoples. I make no theological claims at all, nor any historical argument that Woden was “a real man” as the CFT Team suggests. In fact, I speculate that Woden may have been first regarded as a god (prior to Christianization), and that it is only after early medieval England’s gradual conversion to Christianity that Woden’s role seems to become distinctly defined a legitimizing ancestor for many early medieval kings in England. Perhaps there was an ancient leader named Woden, who is later deified, but the truth is we have no way of knowing for sure.

In sum, and with unfettered conviction, I reject the CFT Team’s problematic distortion of my work. I denounce the arguments being made in ChristiansForTruth’s blog as a racist historical revision and a blatant effort to affirm ahistorical, white supremacist narratives. And, while I responded directly on their website, in a comment on their page (which will probably never be approved), to express my outrage over the misrepresentation of my work, it occurs to me that this can be a teachable moment—both for myself and perhaps for other white medievalists. This is what can happen to our work if we are not careful, and while it is not always possible to control who uses and abuses our scholarship, it is crucial that we give white nationalists as little ammunition for their weaponization of the medieval as possible.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading

Baker, Peter. “Anglo-Saxon Studies After Charlottesville: Reflections of a University of Virginia Professor.” Medievalists of Color (2018).

Dockray-Miller, Mary. “Old English Has a Serious Image Problem.” JSTOR Daily (2017).

Elliott, Andrew B.R. “A Vile Love Affair: Right Wing Nationalism and the Middle Ages.” The Public Medievalist (2017).

Fahey, Richard. “Marauders in the US Capitol: Alt-right Viking Wannabes & Weaponized Medievalism.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2020).

—. “Woden and Oðinn: Mythic Figures of the North” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2015).

—. “Woden: Allfather of the English” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2015).

Franke, Daniel. “Medievalism, White Supremacy, and the Historian’s Craft: A Response.” Perspectives on History (2017).

Gabriele, Matthew. “Vikings, Crusaders, Confederates: Misunderstood Historical Imagery at the January 6 Capitol Insurrection.” Perspectives on History (2021).

—, and Mary Rambaran-Olm. “The Middle Ages Have Been Misused by the Far Right. Here’s Why It’s So Important to Get Medieval History Right.” Time (2019).

—. “Islamophobes want to recreate the Crusades. But they don’t understand them at all.” The Washington Post (2017).

Goodman, Lawrence. “Jousting With the Alt-Right.” Brandeis Magazine (2019).

Heng, Geraldine. “Why the Hate? The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, and Race, Racism, and Premodern Critical Race Studies Today.” In the Middle (2020).

—. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Höfig, Verena. “Vinland and white nationalism.” In From Iceland to the Americas: Vinland and historical imagination, ed. Tim William Machan and Jón Karl Helgason. Manchester University Press, 2020.

Kim, Dorothy. “The Question of Race in Beowulf.” JSTOR Daily (2019).

—. “White Supremacists have Weaponized an Imaginary Viking Past. It’s Time to Reclaim the Real History.” Time (2019).

—. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In the Middle (2017).

—. “The Unbearable Whiteness of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Knight, Ellen. “The Capitol Riot and the Crusades: Why the Far Right Is Obsessed With Medieval History.” Teen Vogue (2021).

Little, Becky. “How Hate Groups are Hijacking Medieval Symbols While Ignoring the Facts Behind Them.” History.com (2018).

Livingstone, Josephine. “Racism, Medievalism, and the White Supremacists of Charlottesville.” The New Republic (2017)

Lomuto, Sierra. “Public Medievalism and the Rigor of Anti-Racist Critique.” In the Middle (2019).

—. “White Nationalism and the Ethics of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Luginbill, Sarah. “White Supremacy and Medieval History: A Brief Overview.” Erstwile: A History Blog (2020).

Mas, Liselotte. “Auschwitz, QAnon, Viking tattoos: the white supremacist symbols sported by rioters who stormed the Capitol.” The Observers (2021).

Mills, Ryan. “The ‘Q Shaman’ on Why He Stormed the Capitol Dressed as a Viking.” National Review (2021).

Müller, Miriam. “Revolting Peasants, Neo-Nazis, and their Commentators.” Medievally Speaking (2021).

Narayanan, Tirumular. “Frazetta’s “Death Dealer” and the Question of White Nationalist Iconography at Fort Hood.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2020).

Olusoga, David. “Black people have had a presence in our history for centuries. Get over it.” The Guardian (2017).

Perry, David. “How to Fight 8chan Medievalism – and Why We Must.” Pacific Standard. (2019).

—. “What to Do When Nazis are Obsessed with Your Field.” Pacific Standard. September 6, 2017.

—. “White supremacists love Vikings. But they’ve got history all wrong.” The Washington Post. (2017).

Rambaran-Olm, Mary. “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting “Anglo-Saxon” Studies.” History Workshop (2019).

—. “Anglo-Saxon Studies [Early English Studies], Academia and White Supremacy.” Medium (2018).

Reed, Sam. “Here’s the Story Behind Those Viking Helmets at the Capitol.” In Style (2021).

Romey, Kristin. “Decoding the hate symbols seen at the Capitol insurrection.” National Geographic (2021).

Schuessler, Jennifer. “Medieval Scholars Joust With White Nationalists. And One Another.” The New York Times (2019).

Sturtevant, Paul B. “Leaving “Medieval” Charlottesville.” The Public Medievalist (2017).

Symes, Carol. “Medievalism, White Supremacy, and the Historian’s Craft.” Perspectives on History (2017).

Vinje, Judith Gabriel. “Viking symbols “stolen” by racists.” The Norwegian American (2017).

Young, Helen. “Why the far-right and white supremecists have embraced the Middle Ages and their symbols.” The Conversation (2021).

—. “White Supremacists love the Middle Ages.” In the Middle (2017).

—. “Re-making The Real Middle Ages (TM).” In the Middle (2014).