Over the past several years, scholars around the world have begun to adopt an expansive view of the medieval world as an interconnected and culturally diverse landscape. While notions of the “Global Middle Ages”[1] will continue to be debated, the concept has provoked critical conversations about the ways in which the migration of people, the exchange of ideas, the circulation of commodities, and the spread of disease shaped the medieval world. Whether the motivation was exploration, piety, diplomacy, knowledge, or profit, the movement of people was a fundamental characteristic of the late medieval Mediterranean world (ca. 1250-1500). While these networks certainly formed the basis for establishing transregional connections, itinerant scholars, merchants, soldiers, and pilgrims were not the only travelers in the medieval world.

Migration could also be involuntary (exile, expulsion and enslavement), prompted by violent repression, or driven by economic necessity. The last few years has seen increased attention to the histories of religious refugees, economic migrants and political exiles in the medieval and early modern world. One important recent contribution, Migrants in Medieval England, c. 500-c. 1500, for example, draws on interdisciplinary research in genetics, linguistics, archaeology, art and literature to illustrate the social and cultural effects of migration on medieval English society.[2] Investigating the phenomenon of migration induced by religious persecution and expulsion, Nicholas Terpstra’s Religious Refugees in the Early Modern World has demonstrated how the forced migration of millions of Jews, Muslims, and Christians across Europe and around the globe shaped the early modern world and profoundly affected literature, art, and culture.[3] Another recent book, Migration Histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone,[4] covers migration histories of the regions between the Mediterranean and Central Asia and between Eastern Europe and the Indian Ocean in the centuries from Late Antiquity up to the early modern era. It includes essays by experts in Byzantine, Islamic, Medieval and African history that provide detailed analyses of specific regions and groups of migrants, both elites and non-elites as well as voluntary and involuntary to enrich our understanding of migration as a complex transhistorical phenomenon that has shaped (and continues to shape) human societies.

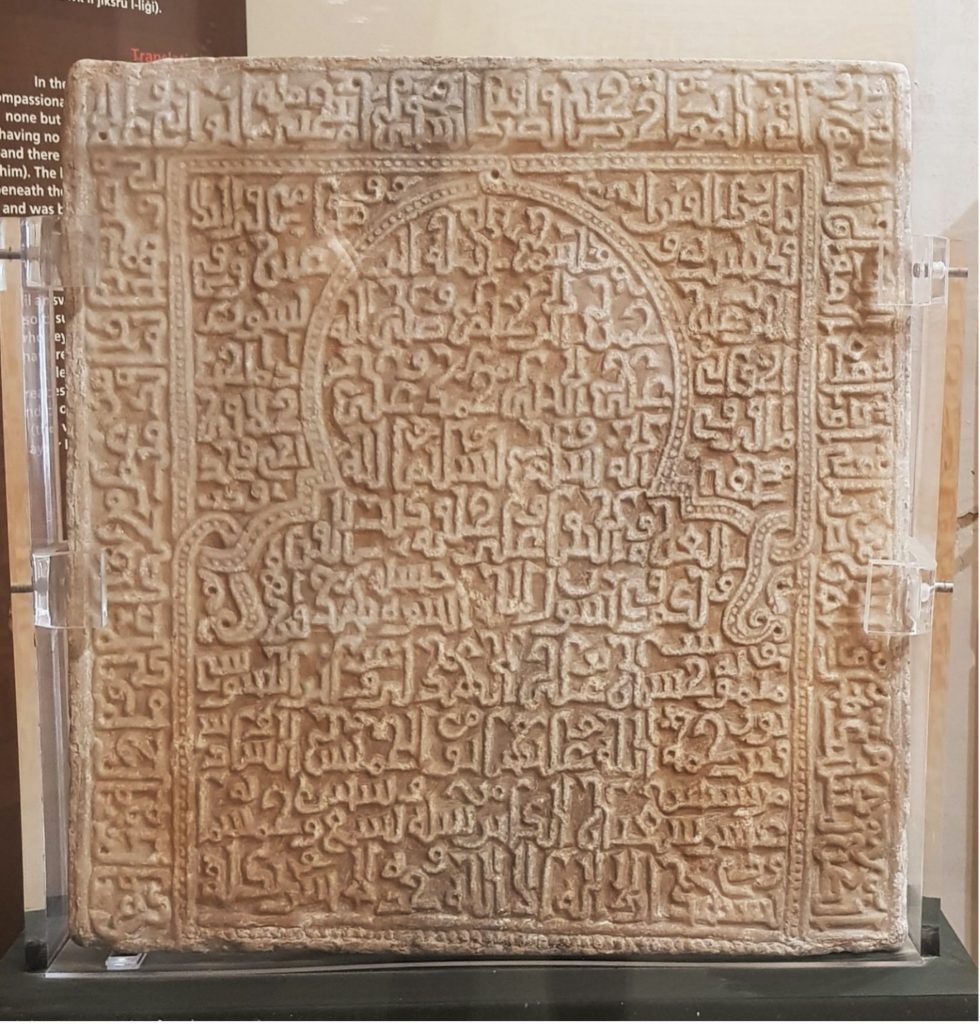

As a modest contribution to this larger scholarly discussion, this piece seeks to draw attention to one particular author, the Muslim traveler Zayn al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ b. Khalīl (1440-1514), whose writings constitute a valuable source for the history of a late medieval Mediterranean world defined by mobility and migration. ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ, a scholar and merchant, was born into a family of administrators and statesmen in Malatya, in eastern Anatolia. He traveled across Syria, Egypt, North Africa and Islamic Spain during the 15th century, and meticulously documented his experiences and observations in his monumental four volume work titled “The Joyous Garden: A Catalogue of the Events and Biographies of the Age” (al-Rawḍ al-Bāsim fī Ḥawādith al-‘Umur wa-l-Tarājim), written around 1483. The pleasant and cheerful title of the work, however, does not reflect its contents, which depicts a complex world that was defined by mass violence, political turmoil and social injustice, as well as by religious coexistence, trade and intellectual exchange. ‘Abd al-Bāsit also provides important evidence for migration that was shaped by economic and political necessity. Perhaps the most important example of this can be seen in two particular anecdotes about a small wave of migration from North Africa to the island of Malta:

“On Wednesday 4 Jumādā II 867/February 24 1463, news spread that a group of people from Misrata, nearly 60 in total, set sail on the Mediterranean and made for the Christian [lit: Frankish] island of Malta, in order to place themselves under their protection and power. They did this because they sought refuge from the oppression and injustice of the military commander Abū Naṣr [b. Jā’ al-Khayr], the governor of Tripoli appointed by the [Hafsid] ruler of Tunis [Abū ‘Amr] ‘Uthmān [r. 1435-1488], who seemed unconcerned and untroubled by this. Verily, there is no power or strength except by God![5]

[…]

“On Thursday 19 Ramadan 867/June 7 1463, we were informed that a group of people from Misrata, nearly 15 in total, sailed for the island of Malta in small boats, along with their families, children and elders in order to settle there under the protection and power of the Christians of the abode of war, in order to flee from the oppression and injustice of the governor of Tripoli. There came news from Malta that the Christians were welcoming, permitting them to settle and granting them land. The [Maltese] stipulated that [the migrants] would pay them as a land tax about one-third or slightly less, as they had been accustomed to paying to the governor of Tripoli, while being protected from injustice and secure in their lives and property. Verily, we are from God and unto him we will return!”[6]

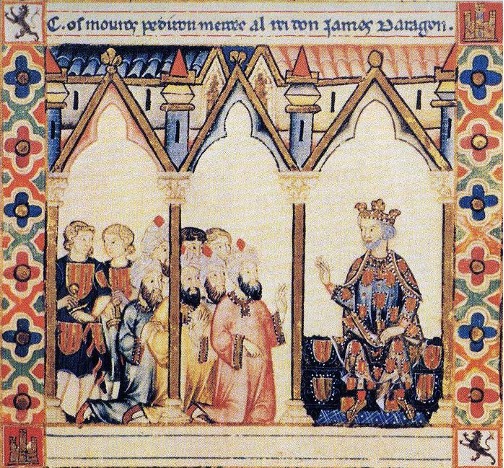

These short textual fragments appear to suggest that on two separate occasions, in February 1463 and June 1463, small numbers of Muslim inhabitants of Misrata, near Tripoli (modern-day Libya), along with their families, voluntarily migrated to Malta to live as farmers under Latin Christian rule. It demonstrates the tremendous agency of these individuals, who sought to escape injustice and hardship by undertaking the (highly) perilous journey to Malta, an island inhabited almost entirely by Christians and which was part of the extensive domains of the Crown of Aragón. The fact that these migrants were welcomed and granted land in Malta is all the more interesting in light of the broader geo-political context and cultural context of the mid-15th century Mediterranean world, which witnessed heightened anxieties, religious tensions and millenarian sentiments following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (May 1453) and the imperial expansion that characterized the reign of Mehmed II (r. 1452-1481).

It reflects the importance of local arrangements, and individual relationships in structuring the politics of the Mediterranean world. While religious hostility, confessional tensions and violence were undoubtedly an important reality that shaped attitudes and policies during this period, this did not preclude collaboration and negotiation across religious and cultural boundaries. There may have even been a demographic and agricultural demand for the types of skills and labor provided by the migrants. Throughout the 15th century, Malta’s population remained relatively small, and was constantly depleted as a result of emigration and enslavement. This meant that there was a surplus of land and a dearth of labor, which posed major problems for an economy that was primarily agricultural. An important testimony of the importance of Malta’s agriculture is provided by the traveler Anselm Adorno, who visited Malta in 1470 and noted that the economy was based largely upon the growth of cotton and cumin.[7] This demand for labor, particularly in the cultivation of cotton, might explain the willingness of the local authorities in Malta to welcome the migrants and grant them land.

The details mentioned by ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ, including the language of sovereignty and mutual obligations, security of lives and property in exchange for a tax, and the specific amount (one-third) of land-tax (kharāj), reflected the particular administrative and political tradition of Muslims residing under Latin Christian rule as laborers, farmers ad tax-paying subjects. There were important antecedents for this arrangement in the medieval Mediterranean, particularly in medieval Spain, Norman Sicily and the Crusader Kingdoms in the Near East.[8]

Significantly, while underscoring the perceived transgression of social and religious boundaries in the migration of these individuals from Islamic lands to Latin Christendom, ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ does not seek to represent the migrants themselves as particularly nefarious. Rather, the emphasis on the fact that they were compelled by necessity and desperation to “flee” and “seek refuge” from the injustice of the Hafsid governor of Tripoli reflects a particular concern with social injustice and political repression as a cause of migration. ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ describes the governor of Tripoli, whose name was Abū Naṣr [b. Jā’ al-Khayr], as “among the worst tyrants who had no fear of God and governed his subjects in the worst possible way.” He also states that “I have been informed that each year he sends over 100,000 gold dinars…which he extracts through an oppressive regime of taxation that imposes hardships on the people.”[9] This explicitly connected Abū Naṣr’s oppressive conduct with his burdensome fiscal policies. Significantly, the emphasis in his passage about the migrants to Malta was not that they would be paying considerably less taxes, since it is stated that they would pay the amount that “they had been accustomed to paying to the governor of Tripoli.” Rather, ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ suggests that they would “be protected from injustice and secure in their lives and property.” As such, the inclusion of this anecdote was an attempt to make a broader claim about the nature of justice and its importance for establishing a stable society. ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ considered the migration of the inhabitants of Misrata to be a lamentable and deplorable state of affairs, which reflected poorly upon both Abū Naṣr as well as the Hafsid sovereign Abū ‘Amr Uthmān, who he represents as showing little interest in the well-being of his own subjects. Migration, then, could be seen as constituting part of a larger polemic that sought to cast aspersions upon the legitimacy of Hafsid rule. The idea that the inhabitants of Misrata preferred to reside under Latin Christian rule than under Islamic political authority would have been an effective way to emphasize this point.

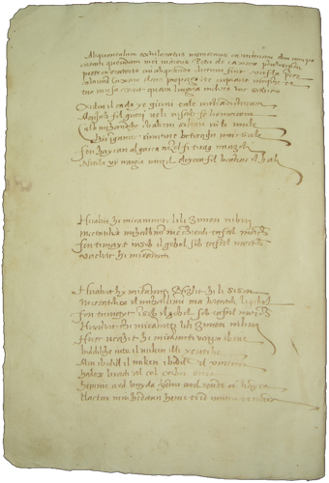

So, one might ask, why Malta? What factors shaped the decision of these migrants to sail to this Christian island? It is particularly significant that they chose to migrate to Malta in particular. It demonstrates the importance of linguistic affinities, as well as the practical considerations of migration. Their decision to journey to Malta was probably motivated by the fact that the Maltese vernacular was essentially a dialect of Arabic which was intelligible to the inhabitants of Misrata. This fact is attested by many of the surviving documents and literary sources from this period.[10] One of the most important of these is the Il-Kantilena, the oldest known literary text in the Maltese language, authored by the Maltese poet and philosopher Pietru Caxaro (d. 1485) during the late 15th century.[11] Il-Kantilena is notable for its extensive Arabic vocabulary, demonstrating its relationship and proximity to the Siculo-Arabic spoken in Sicily during the 11th-13th centuries. The close association between Malta and the Arabic language of its inhabitants was frequently invoked as a fundamental characteristic of the island well into the early modern period. The Morisco notable Francisco Núñez Muley (d. after 1567), for example, writing in Granada (Spain), proclaimed that “those who live on the not-so-distant island of Malta are Catholic Christians and nobles who speak Arabic and use Arabic to write texts having to do with the Holy Catholic faith and other Christian matters. I also believe that they say mass in Arabic.”[12] Despite the religious differences between the Maltese Christians and the Muslim inhabitants of Misrata, the Arabic language and shared history would have served as a common source of affinity. This did not preclude the existence of serious tensions, of course, but it would have certainly enabled the migrants to communicate with their new hosts and negotiate the terms of their arrival and settlement.

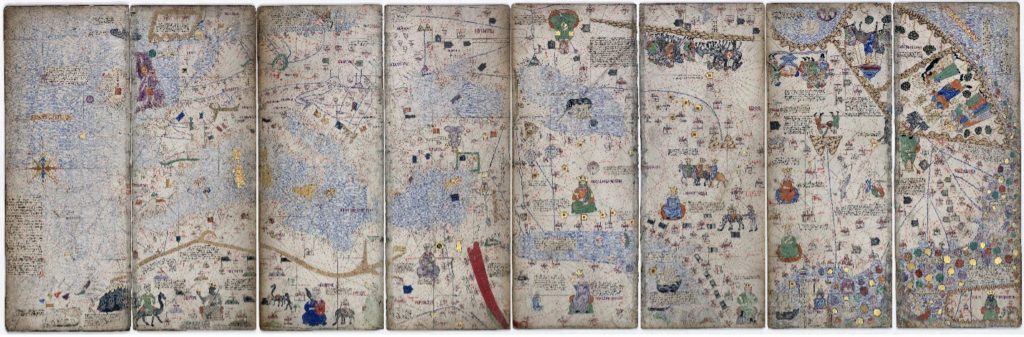

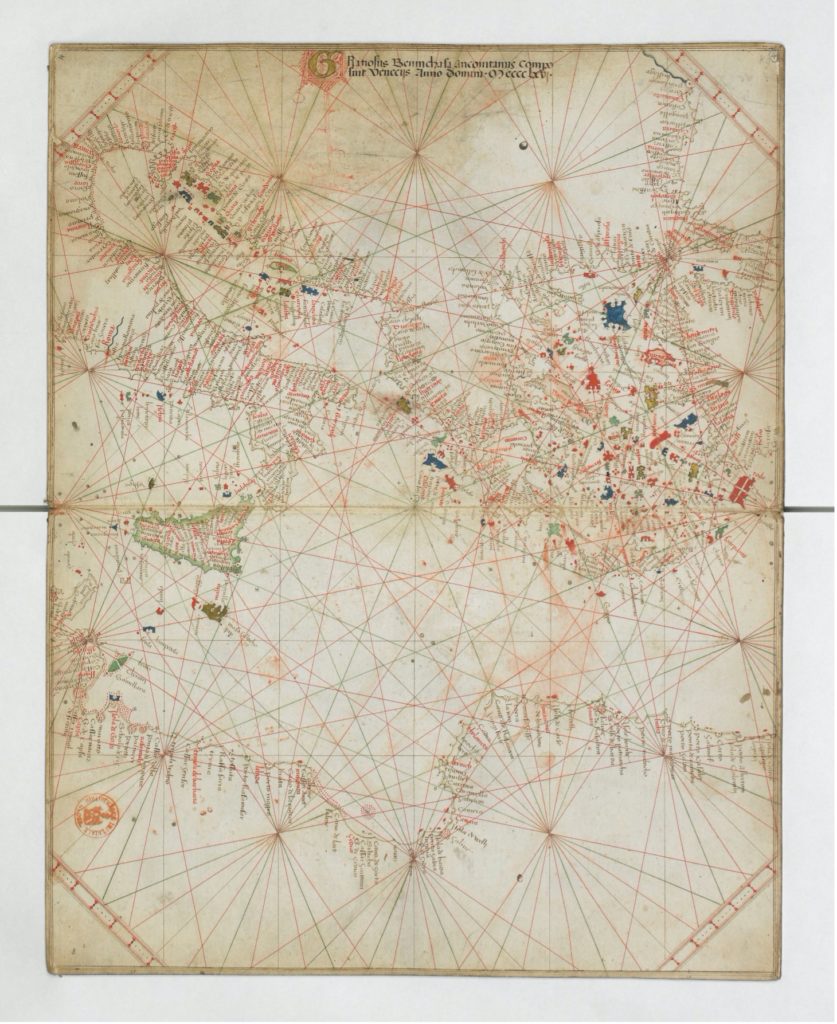

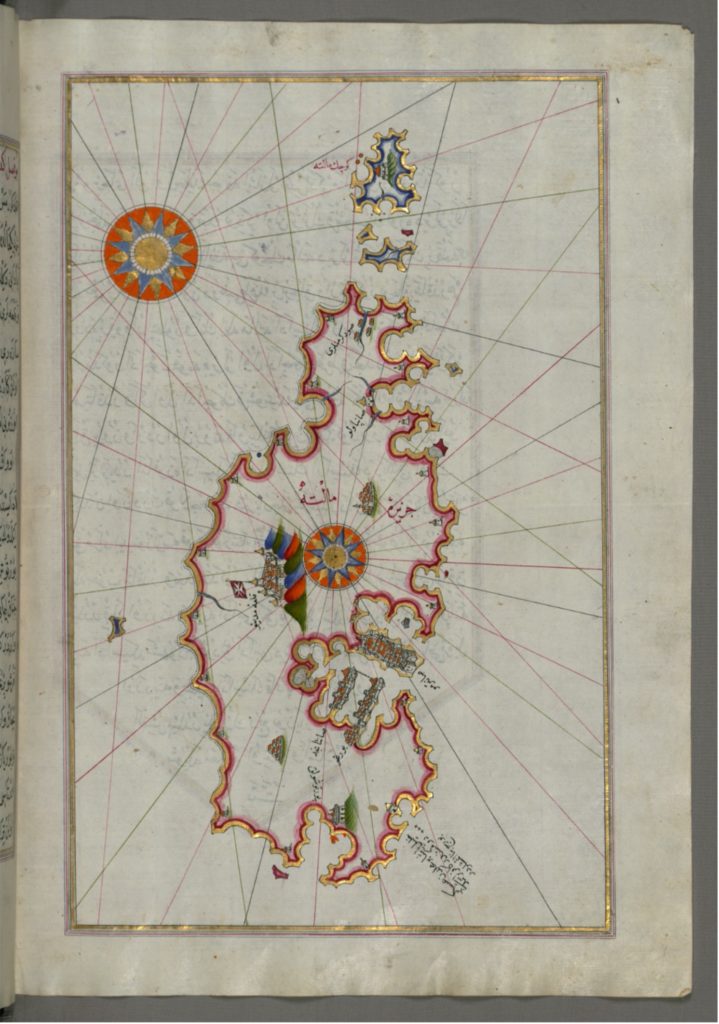

There was also another, more practical reason why these migrants would have sailed to Malta. The island was located nearby, approximately 400 km north of Misrata, directly off a major sailing route (as indicated by the many portolan charts from the 15th century). Malta would also have been quite familiar to the inhabitants of Misrata as a result of the various connections, including both trading and raiding, which had existed for centuries. In addition to being under Islamic rule from 870 to 1091, there is evidence to indicate that there were still numerous Muslim families living on the royal estates of the islands of Malta and Gozo as late as the mid-13th century.[13] Several decades before the migrants from Misrata made their journey, the Hafsid royal fleet had besieged Malta in September 1429, devastating the island and enslaving a large part of the island’s population.[14] It is plausible that many of these enslaved peoples would have been known to the inhabitants of Misrata, and some of them may have even been among the migrants themselves.Commercial activity and intermittent warfare would have intimately bound the two regions together, and fostered a certain familiarity between the inhabitants of the Muslim-Christian borderlands in the central Mediterranean.

It is also plausible that these individuals from Misrata were following a common route of migration, and were hardly the first to make the journey. The phenomenon of migration from North Africa to Malta during the late 14th and early 15th century may also be attested by onomastics. As Godfrey Wettinger has shown, the name “Muhammed” and its various forms (muhumudi, muhamud, muhumud) appears as a surname for several individuals in a 1419 militia roll from Malta, but is unattested as a surname in the rosters of 1480.[15] Without further research and evidence, it is difficult to speculate, but the questions remain: did this name belong to migrants from North Africa? What explains its disappearance by 1480? Does this reflect the processes of conversion and assimilation as part of the integration of these individuals into Maltese Christian society?

While it is plausible that ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ’s account about the migration from Misrata to Malta in the 15th century was a didactic story that sought to caution readers against political injustice and fiscal oppression, this post has attempted to encourage further inquiry into the question of economic migration in the medieval Mediterranean world. While much more research into the extensive and well-preserved Maltese archives will certainly bring much more evidence about the relationship between medieval Malta and North Africa to light, this particular episode underscores the importance of economic and political circumstances, individual agency and religious boundaries in shaping the history of migration in the late medieval Mediterranean world. Although distinctly medieval in a number of ways, it raises important questions about the role of migration, voluntary or otherwise, in shaping human societies over the centuries.

Mohamad Ballan

Mellon Fellow, Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame (2021-2022)

Assistant Professor of History

Stony Brook University

[1] For an important overview and discussion of this concept, see Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen, “Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages,” Past & Present, Volume 238, Issue suppl_13, November 2018, pp. 1–44, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gty030

[2] W. Mark Ormrod, Joanna Story, and Elizabeth M. Tyler (eds.), Migrants in Medieval England, c. 500-c. 1500 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[3] Nicholas Terpstra, Religious Refugees in the Early Modern World: An Alternative History of the Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[4] Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, Lucian Reinfandt, and Yannis Stouraitis (eds.), Migration Histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone: Aspects of Mobility between Africa, Asia and Europe, 300-1500 C.E. (Leiden: Brill, 2020). Available in Open Access : https://brill.com/view/title/55556

[5] Zayn al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ b. Khalīl al-Ḥanafī, Kitāb al-Rawḍ al-Bāsim fī Ḥawādith al-‘Umur wa-l-Tarājim (Beirut: al-Maktabah al-‘Aṣriyyah, 2014), ed. ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Salam Tadmuri, 2: 214.

[6] Zayn al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ b. Khalīl al-Ḥanafī, Kitāb al-Rawḍ al-Bāsim fī Ḥawādith al-‘Umur wa-l-Tarājim (Beirut: al-Maktabah al-‘Aṣriyyah, 2014), ed. ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Salam Tadmuri, 2: 224-225.

[7] Brunschvig, Robert Brunschvig, Deux récits de voyage inédits an Afrique du Nord au XVe siècle (Paris : Maisonneuve & Larose, 1935), 143.

[8] For an important study of this phenomenon, see Brian Catlos, Muslims of Medieval Latin Christendom, c. 1050-1614 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[9] Zayn al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ b. Khalīl al-Ḥanafī, Kitāb al-Rawḍ al-Bāsim fī Ḥawādith al-‘Umur wa al-Tarājim (Beirut: al-Maktabah al-‘Aṣriyyah, 2014), ed. ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Salam Tadmuri, 2: 220-221.

[10] For a discussion of Maltese vernacular during the medieval and early modern period, see Godfrey Wettinger, “Plurilingualism and Cultural Change in Medieval Malta,” Mediterranean Language Review, Vol. 6-7 (1990-1993), 144-160

[11] M. Ballan, “Il-Kantilena: A 15th-century Poem in Medieval Maltese” https://ballandalus.wordpress.com/2019/04/08/il-kantilena-a-15th-century-poem-in-medieval-maltese/

[12] Francisco Núñez Muley, A Memorandum for the President of the Royal Audiencia and Chancery Court of the City and Kingdom of Granada (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), trans. Vincent Barletta, 92.

[13] Ayşe Devrim Atauz, Eight Thousand Years of Maltese Maritime History : Trade, Piracy, and Naval Warfare in the Central Mediterranean (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008), 53.

[14] Robert Brunschvig, La Berbérie orientale sous les Ḥafṣides des origines à la fin du XVe siècle (Paris : Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1940), 230-232.

[15] Godfrey Wettinger, “The Distribution of Surnames in Malta in 1419 and the 1480s,” Journal of Maltese Studies 5 (1968), 42; Godfrey Wettinger, “The Militia List of 1419-20 : a New Starting Point for the Study of Malta’s Population,” Melita Historica, 5 (1969), 80-105.