When I walked by this building on my way to Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art this past July, one of my five-year-old twins asked, “Mama, is that a castle?” Could there be clearer evidence that this building looks medieval?

But, why? It seems odd for such an ornate, crenellated structure to sit amidst a conglomeration of Chicago skyrises and modern store fronts along the Magnificent Mile. It almost doesn’t fit this urban landscape. Almost.

It might seem even weirder to learn that this miniature, limestone “castle” is a 19th-century water tower, a building intended for practical, mechanical use in an industrial age, rather than for fortification and housing for the aristocracy. The tower contains a water pump originally constructed to draw water out of Lake Michigan and provide some much-needed clean water to the city. Its function is decidedly not medieval. So, then, why does it look like a castle? Because it is part of the Gothic Revival movement, which many of the period’s great thinkers, writers, and artists imported to the States from across the Atlantic. The tower’s architect, William W. Boyington, designed this building and its neighboring pumping station, built in a matching style, with medieval architecture in mind. He might even have drawn inspiration from a specific medieval building: the Cloth Merchant’s Hall of Bruges in Belgium (known as the Belfry), illustrated, as chicagoarchitecture.org suggests, in nineteenth-century architectural writings. If true, then a perhaps unexpected turn of events brought the medieval cloth trade, with its rich and complex history, face to face with 19th-century industrial innovation several thousand miles away and many centuries in the future. Such are the vagaries of history.

From the Statement of Significance on the Nomination form in the National Register of Historic Places Inventory: “The Water Tower and Pumping Station serve as an architectural link with Chicago’s pre-fire history in the central area of the city. [...] Although not an architectural tour de force, the buildings are typical of the aesthetic of the 19th century, that a building should be both utilitarian and architecturally pleasing...”

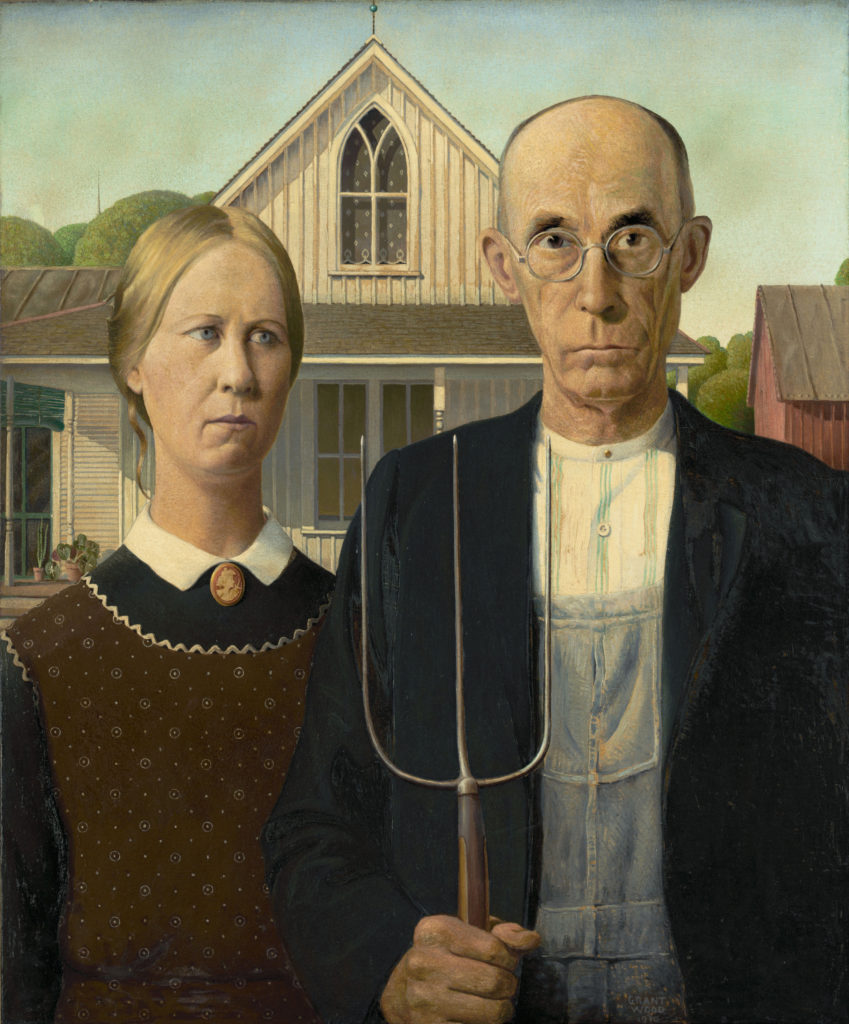

But, what does it mean for this building to be part of the Gothic Revival movement, and what exactly is medieval about this 19th-century period of architecture? The term “gothic” is itself a problematic, but fascinating one. Used by art historians and in pop culture, the word, capacious in its ever-shifting connotations, receives no less than six definitions, most of which break down into multiple sub-definitions, in the Oxford English Dictionary. Its range of positive and negative meanings include everything from references to the Goths (the original people and their language, not the modern teenager), an adjectival denotation for the “barbarous” or “uncouth,” and a style of medieval architecture from the 12th to 16th centuries, all the way to the resurgence of this medieval style during the Revival. Its meanings diverge even further when considering the word’s use in various disciplines: paleographers, for instance, study gothic manuscripts and bookhands, while literary critics will more likely associate the gothic with particular settings and horror genres. In America, variations of gothic buildings became so engrained in the culture that some features even made their mark on humble houses and farm buildings, spreading through rural territories and becoming iconically embraced in the famous Grant Wood painting, “American Gothic,” a mainstay and personal favorite of mine on display at Chicago’s Art Institute (notice the pointed-arch window in the “Carpenter Gothic” house behind them). The term’s ties to the Middle Ages, therefore, can be either strictly or loosely construed as genuinely medieval, or a form of medievalism.

As an architectural style, the gothic building has been variously understood as barbaric and ugly, or beautiful and natural at different points in the word’s history. And, as Matthew Reeve reminds us, the word gothic was coined after the Middle Ages “to articulate a perceived aesthetic, intellectual, and artistic chasm between the period in which the word is employed and the medieval past. In this sense Gothic is less suggestive of the nature of the Middle Ages itself than it is of the culture’s perceived temporal and ideological distance from it” (233). Perceptions of this style have therefore shifted periodically according to the changing political, social, and cultural climates of successive generations. However, the 19th century played a major role in the formation of this word’s current and generally more positive definition, and Boyington’s work represents a part of Chicago’s efforts to participate in this widespread architectural tradition. Whereas the 18th-century Romantic era solidified Gothic architecture’s reputation as evoking “mysticism and sublimity,” 19th-century perceptions of this style introduce further associations with “national identity” and “a structurally rational approach to design” (Murphy 92). In this case, Boyington’s position so late in the Gothic Revival might indicate that for him, the Gothic style was as much about beauty and emotion as it was about rationality and functionality, a feat of scientific engineering in which appearance and use value both become valued players.

Still, as an artifact of 19th-century medievalism, the water tower makes no attempt at genuine authenticity. Its miniature size, pristine facade, and local building materials distinguish it less as an inadequate imitation than as something altogether new. It draws on the medieval past in a way that enables the architect to preserve a carefully chosen European heritage as part of the young nation’s own identity, while at the same time speaking to a new place in a new historical moment. The very nature of this form of creativity, transforming the past into a reinvented present, makes this “Gothic City” the perfect backdrop for countless other creative projects, including the inspiration Chicago often provides for the look and feel of none other than “Gotham City” itself.

Stay tuned for Part 2, forthcoming during the spring 2019 semester...

Karrie Fuller, PhD

University of Notre Dame

Online Resources:

“Boyington, William W.,” Ryerson and Burnham Archives: Archival Image Collection, TheArt Institute of Chicago, accessed on November 1, 2018, http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm/search/collection/mqc/searchterm/Boyington,%20William%20W./mode/exact.

Gale, Neil. “The History of the Chicago Water Tower,” The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal, published on December 3, 2016, https://drloihjournal.blogspot.com/2016/12/chicago-water-tower-history.html.

“Illinois SP Chicago Avenue Water Tower and Pumping Station,” National Register of Historic Places, National Archives Catalog, National Park Service, accessed on October 19, 2018, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/28892376.

Leroux, Charles. “The Chicago Water Tower,” Chicago Tribune, published on December 18, 2007, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-watertower-story-story.html.

“Throwback Thursday: Chicago Water Tower Edition,” Chicago Architecture, Artefaqs Corporation, published on March 5, 2015, https://www.chicagoarchitecture.org/2015/03/05/throwback-thursday-chicago-water-tower-edition/.

Works Cited & Further Reading

Blackman, Joni Hirsch. This Used to Be Chicago. St. Louis, MO: Reedy Press, 2017.

Carbutt, John. Biographical Sketches of the Leading Men of Chicago, 215-22 . Chicago: Wilson & St. Clair, 1868. [Written in a dated style, this book is florid, grandiose, and male-centric, but contains some useful information about Boyington nevertheless.]

Draper, Peter. “Islam and the West: The Early Use of the Pointed Arch Revisited.” Architectural History48 (2005): 1-20.

Frankl, Paul. Gothic Architecture. Revised by Paul Crossley. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962, 2000.

Grodecki, Louis. Gothic Architecture. New York: Electa/Rizzoli, 1978.

Murphy, Kevin D. and Lisa Reilly. “Gothic.” In Medievalism: Key Critical Terms, 87-96. New York: Boydell and Brewer, 2014.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Gothic,” accessed September 20, 2018, http://www.oed.com.proxy.library.nd.edu/view/Entry/80225?redirectedFrom=gothic#eid.

Reeve, Matthew M. “Gothic.” Studies in Iconography33 (2012): 233-246.

Schulz, Frank, and Kevin Harrington. Chicago’s Famous Buildings. 5thed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Ziolkowski, Jan M. The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Vol.3: The Making of the American Middle Ages. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0146.

The Wife of Bath certainly knew how to ‘knock em dead’ with her looks, or at least with her sense of fashion. She is not a shy character, so we shouldn’t expect her closet to be either. It was her goal to stand out and look the part, and with her “scarlet reed” hose, she surely made an entrance. Red is a very vibrant and sensual color, and the Wife of Bath is a very sexual individual. It is no wonder that she would be wearing something as daring as red pantyhose beneath her skirt. Part of Taylor Swift’s fame stems from her image and fashion just as it does with the Wife of Bath. When attending public events, Taylor’s outfits always get mentioned in the next day’s ‘hot or not’ gossip articles. Also, similarly to the Wife of Bath, Swift has an affinity for the color red. It is a rare moment to see Swift pictured without the bright tint added to her perfect pout. Both of these popular women allow their looks to drive their brand and fully shape who they are and, more importantly, how they want the world to see them.

The Wife of Bath certainly knew how to ‘knock em dead’ with her looks, or at least with her sense of fashion. She is not a shy character, so we shouldn’t expect her closet to be either. It was her goal to stand out and look the part, and with her “scarlet reed” hose, she surely made an entrance. Red is a very vibrant and sensual color, and the Wife of Bath is a very sexual individual. It is no wonder that she would be wearing something as daring as red pantyhose beneath her skirt. Part of Taylor Swift’s fame stems from her image and fashion just as it does with the Wife of Bath. When attending public events, Taylor’s outfits always get mentioned in the next day’s ‘hot or not’ gossip articles. Also, similarly to the Wife of Bath, Swift has an affinity for the color red. It is a rare moment to see Swift pictured without the bright tint added to her perfect pout. Both of these popular women allow their looks to drive their brand and fully shape who they are and, more importantly, how they want the world to see them.