What do Gospel books have in common with collections of medical recipes? What do practices of erasure and destruction tell us about early Christian identity? Can we tell biographies of books?

Early Christians materialized Gospel literature in diverse formats and technologies. As material objects, these instantiations of “the Gospel” participated in ritual, political, economic, and readerly contexts. Gospel books were powerful. Augustine of Hippo complains that his audiences put Gospel books under their pillows to cure toothache. Amulets attest that even short excerpts enabled users to access the protective power of the material Gospel. The Gospel codex sometimes represented Christian identity, as Gospel books were processed in liturgy and imposed on the shoulders of ordinands. In times of persecution, Gospel books might even be subject to public execution in place of Christ himself. Yet Gospel books might also be erased or destroyed for apparently more mundane reasons, as various kinds of recycling attest. As an anthological object, the multiple-Gospel codex contributed to the development of a fourfold canonical Gospel. Early Christian readers developed novel strategies to facilitate knowledge, navigation, and use of Gospel literature. In each of these contexts, the materiality of Gospel literature plays a decisive role.

To address this theme, David Lincicum and I organized a conference on The Material Gospel at Notre Dame on 31 May 2019. The conference was generously sponsored by the Medieval Institute, the Institute for the Study of the Liberal Arts, and the Department of Theology. It brought together a number of scholars of Gospel literature and material culture to discuss the Gospel as a material object in the early Christian centuries. The day-long conference involved six papers and extended discussion between speakers and audience members.

To address this theme, David Lincicum and I organized a conference on The Material Gospel at Notre Dame on 31 May 2019. The conference was generously sponsored by the Medieval Institute, the Institute for the Study of the Liberal Arts, and the Department of Theology. It brought together a number of scholars of Gospel literature and material culture to discuss the Gospel as a material object in the early Christian centuries. The day-long conference involved six papers and extended discussion between speakers and audience members.

To begin the day, Clare Rothschild (Lewis University) offered a paper on “Galen’s De indolentia and the Early Christian Codex.” The codex, a book format with pages and covers, quickly became a marker of Christian practices — to such an extent that scholars have suggested that the codex format became a marker of Christian identity, perhaps even chosen because of its visual distinctiveness. Rothschild intervenes in this conversation, emphasizing that the early Christian preference for a codex format was not only about visual distinctiveness or the perceived value of the texts, but also about the utility of the codex format. Comparison with the second-century physician Galen (129–ca. 216 CE) offers one window into second-century use of the codex. Rothschild offers a close reading of a passage where Galen describes the loss of parchment codices with medical recipes and of his own medical treatises. Similar genres appear in both formats. Galen describes the codices of recipes as having enormous intellectual and pecuniary value, but one of his own treatises, written on a scroll, was even more precious. But if the codex format was neither a bibliographic marker of genre or an indication of value, then why might Galen have used it? And why might Christians have adopted this technology? Rothschild argues that the codex affords durability, accessibility, expandability, and portability. These practical possibilities make it appropriate and convenient for Galen’s collections of medical recipes. Similarly, the codex format is practical for early Christian practices of study, liturgy, and travel in ways that exceed the possibilities of the bookroll. Conversations about the early Christian adoption of the codex for Gospels and other texts must, therefore, attend to the utility of the codex.

In a paper on “Navigating the Gospel: Nonlinear Access and Practical Use,” Jeremiah Coogan (Notre Dame) expands the conversation about the materiality of early Christian Gospel reading beyond the issue of codex format. Coogan argues that technologies for finding, dividing, and referencing illuminate late ancient Gospel reading, revealing how readers use Gospel books as objects. Coogan compares the modes of access invited by Gospel books with other practical texts in classical and late antiquity. Gospel books share visual features and practical affordances of access with recipe collections (like Galen’s or Scribonius Largus’), ritual (“magical”) anthologies (like PGM IV), and agricultural handbooks (like that of Columella). Paratextual interventions facilitate and expect Gospel access in various nonlinear ways — for liturgy, for divination, for moral instruction, for study. The late ancient Gospel book as an object frequently functions more like a recipe book than a linear text (such as the Iliad). Here, as in Rothschild’s paper, the focus is on the modes of use to which Gospel books as objects are suited. At the same time, the conversation must move beyond the codex as such, since Gospel books participate in material and paratextual conventions that facilitate access but that are not native to the codex. Coogan offers enlarged frames of comparison for the physicality and use of late ancient Gospel books.

In a paper on “Navigating the Gospel: Nonlinear Access and Practical Use,” Jeremiah Coogan (Notre Dame) expands the conversation about the materiality of early Christian Gospel reading beyond the issue of codex format. Coogan argues that technologies for finding, dividing, and referencing illuminate late ancient Gospel reading, revealing how readers use Gospel books as objects. Coogan compares the modes of access invited by Gospel books with other practical texts in classical and late antiquity. Gospel books share visual features and practical affordances of access with recipe collections (like Galen’s or Scribonius Largus’), ritual (“magical”) anthologies (like PGM IV), and agricultural handbooks (like that of Columella). Paratextual interventions facilitate and expect Gospel access in various nonlinear ways — for liturgy, for divination, for moral instruction, for study. The late ancient Gospel book as an object frequently functions more like a recipe book than a linear text (such as the Iliad). Here, as in Rothschild’s paper, the focus is on the modes of use to which Gospel books as objects are suited. At the same time, the conversation must move beyond the codex as such, since Gospel books participate in material and paratextual conventions that facilitate access but that are not native to the codex. Coogan offers enlarged frames of comparison for the physicality and use of late ancient Gospel books.

Practices of reading and access are embedded in larger discourses. In his paper on “The Gospel Read, Sliced, and Burned: The Material Gospel and the Construction of Christian Identity,” Chris Keith (St. Mary’s Twickenham) argues that the use of the Gospel as a material object becomes part of early Christian identity. Drawing on the work of anthropologist Jan Assman , Keith argues that the early Christian book functioned as a material locus of memory and tradition. Far from being secondary or peripheral, textual objects become part of the visualization of literary memory. Practices of Gospel reading shape Christian understandings of the Gospel book as object. Christians read Gospel books in ways that are strikingly similar to how Jewish communities read Scriptures. However, there is a conceptual replacement of Torah with “Gospel” in (some) early Christian reading practices. Through practices of public reading, the book becomes a cult object. As a result, early Christians think in decidedly literal (and yet metaphorical) terms about textual change. Early Christians imagined Marcion of Sinope’s textual editing as gnawing, slicing amputation. Textual change is construed as an assault upon physical objects themselves. Finally, the centrality of the Christian book as object becomes a key issue in persecution under the Emperor Diocletian in the early fourth century. In seeking to destroy the Christian book, Rome attests its central significance as material object. For Eusebius, to destroy either churches or material texts is an attack upon Christianity. The construction of Christian identity is about what one does with the material Gospel.

Practices of reading and access are embedded in larger discourses. In his paper on “The Gospel Read, Sliced, and Burned: The Material Gospel and the Construction of Christian Identity,” Chris Keith (St. Mary’s Twickenham) argues that the use of the Gospel as a material object becomes part of early Christian identity. Drawing on the work of anthropologist Jan Assman , Keith argues that the early Christian book functioned as a material locus of memory and tradition. Far from being secondary or peripheral, textual objects become part of the visualization of literary memory. Practices of Gospel reading shape Christian understandings of the Gospel book as object. Christians read Gospel books in ways that are strikingly similar to how Jewish communities read Scriptures. However, there is a conceptual replacement of Torah with “Gospel” in (some) early Christian reading practices. Through practices of public reading, the book becomes a cult object. As a result, early Christians think in decidedly literal (and yet metaphorical) terms about textual change. Early Christians imagined Marcion of Sinope’s textual editing as gnawing, slicing amputation. Textual change is construed as an assault upon physical objects themselves. Finally, the centrality of the Christian book as object becomes a key issue in persecution under the Emperor Diocletian in the early fourth century. In seeking to destroy the Christian book, Rome attests its central significance as material object. For Eusebius, to destroy either churches or material texts is an attack upon Christianity. The construction of Christian identity is about what one does with the material Gospel.

Practices of book destruction, however, are not always violent or polemical. In her paper on “Erasing the Gospels: Insights from the Sinai Syriac Gospel Palimpsest,” Angela Zautcke (Notre Dame) analyzes the palimpsesting (erasing and rewriting) of late ancient Gospel books. Focusing on Syriac manuscripts, especially those held at St Catherine’s Monastery (Sinai, Egypt) and the British Library (many also from Sinai). Zautcke focuses on the potential role of erasure as intentional destruction, and concludes that there is no evidence to suggest that obsolete textual traditions like the Old Syriac Gospels were more likely to be palimpsested than other kinds of texts. Rather, parchment Gospel books often circulated for some four centuries before being recycled for other texts. The preponderance of palimpsested texts in the extant monastery collections have various scriptural texts (not always Gospels) as the undertext, reflecting the predominance of these texts in the existing collections available for palimpsesting. Zautcke demonstrates the need for further study of palimpsesting in material and social histories of early Christian texts, but concludes that the destruction of Gospel books by erasure is part of the life- cycle of the Gospel as object. The medium often continues past the text itself.

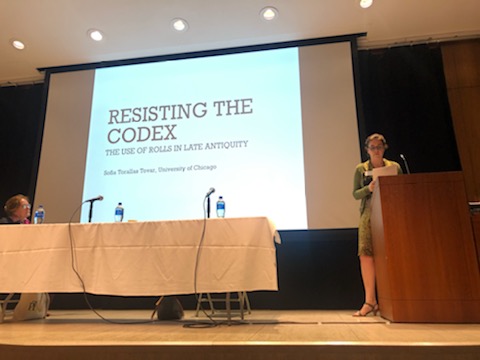

Returning to the issues of codex and roll, Sofía Torallas Tovar (University of Chicago) discussed the opposite case in a paper on “Resisting the Codex: Christian Rolls in Late Antiquity.” While modern scholarly imaginations associate early Christian book culture with the emergence of the codex, Torallas Tovar demonstrates that scrolls continue to function in a range of contexts. While the codex becomes a standard format for some kinds of Christian literature, the media ecology of Christian texts also includes the continued use of scrolls — for episcopal letters, for texts like Didache and Jubilees, and for day-to-day letters and documents. Both the codex and the roll belong in a wider landscape of late ancient Christian material texts.

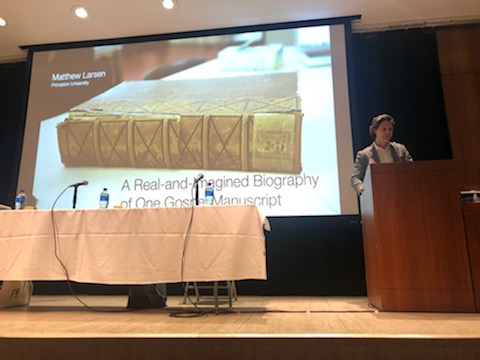

Finally, Matthew Larsen (Princeton) offered a paper on “Codex Bobiensis: A Real-and-Imagined Biography of One Gospel Manuscript.” Applying a model of “real-and-imagined” history from the work of Heather Blair, Larsen narrated the biography of the Latin Gospel manuscript known as Codex Bobiensis (Turin National University Library, G.VII.15), from its production in Roman North Africa to its current dismembered state in Turin. This manuscript offers an unusual — and often ignored — Gospel text and an even more unusual hybridized epitomized form, combining Mark and Matthew. It takes its common name from Bobbio Abbey, where it was preserved in part because of a remembered association with the Irish missionary Columbanus (ca. 540–615 CE). The story of this object ends (for now) in Turin, where the manuscript exists as a collection of dismounted folios. Larsen’s paper offers new lenses with which to examine the continued and changing materiality of Gospel texts as objects.

Jeremiah Coogan, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame