The “Chorister’s Lament,” a late fourteenth-century alliterative poem inserted into empty space in London, British Library, Arundel MS 292 (ff. 70v-71r), offers humorous insight into the practice of learning to sing in a fourteenth-century Northeast Midlands monastery, as novice choristers Walter and William bewail their inability to demonstrate the proficiency expected of them by their French singing master. Highly technical musical vocabulary fills the piece and has perhaps encouraged scholars and anthologizers to give the poem a wide berth. A few of these terms, including one especially rare, point to a decidedly English musical terminology and suggest a connection between the “Chorister’s” poet and a little-studied 14th century musical treatise with English roots.

The most obscure word used by the Chorister-poet is the extremely rare streinant:

‘Yet ther is a streinant with two longe tailes;

Therfore has oure maister ofte horled my kailes (bowled my skittles)

The Oxford English Dictionary calls the streinant “a musical note written with two stems; a breve” and suggests that the word may be related to the equally obscure Old French word estraignant. The dictionary entry cites only one occurrence of the word in English – this Chorister’s passage – and scholars have not had much luck tracking it from there. The word does exist elsewhere, in a Latin manuscript from England – in a treatise called the Metrologus, a 14th century commentary on Guido of Arezzo’s Micrologus.[1]

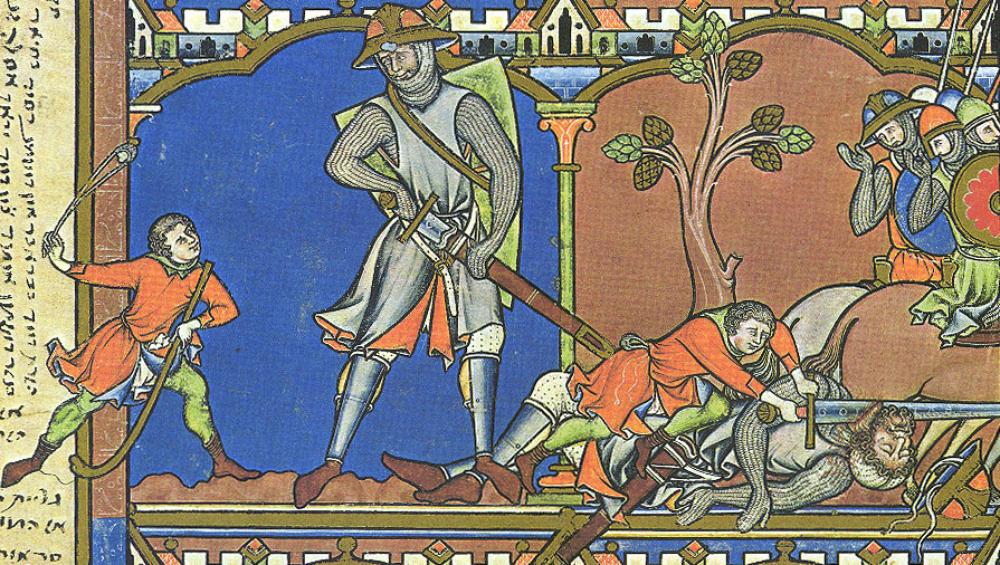

The copy of the Metrologus found in Rome, Bib. Vat. Reg. Lat. 1146, 67r-70v, mentions the streinant three times. Most importantly, the text defines the streinant and its use (Item est alia nota quae vocatur streinant et ponimus super istis videlicet mon. ton. an. in. cum. num. et super consimiles et continet in se duas breves in cantando. “Also there is another note which is called streinant and which we put above these, plainly, mon. ton. an. in. cum. num., and above like things and contains in itself two breves in singing”) and also gives an example of how the streinant looks on the page (et figuratur sic.) According to the definition provided by the treatise, the streinant is used as a mensural quantity – one streinant is worth two breves. The manuscript page containing several examples of the streinant can be accessed here.

The manuscript tradition points squarely at a 14th century English source for the Metrologus,[2] as does the English cursive of this copy. The Metrologus commentator and the “Chorister’s” poet were likely near contemporaries working in the same region of England. The two share the rare streinant as well as other especially English words. Is there a link between the Chorister’s poet and this treatise? Perhaps William and his singing master first met the streinant in the Metrologus.

Rebecca West

University of Notre Dame

[1] The definitive medieval treatise on music theory.

[2] Jos. Smits van Waesberghe, ed., Expositiones in Micrologum Guidonis Aretini. Musicologica Medii Aevi. (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1957), 62.