Of the many issues that rose to the fore in the course of the conflicts between the Latin and Greek churches during the Middle Ages, one of the most consistent, and to me, surprising, was the repeated accusation that the Greeks rebaptized Latin Christians when they, for whatever reason, wished to switch their ritual use (what we would now understand as a “conversion” between different denominations). Although the veracity of these claims has been debated, I think, as I have written elsewhere, that there is good reason to believe that the Greeks really did rebaptize Latins. Complaints about the practice began in the mid-11th century with Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida, who was elsewhere highly accurate in his claims about liturgical practice, and continue well into the 13th century, including an honorable mention in the canons of the Fourth Lateran Council under Pope Innocent III.

What is less clear, though, is why the Greeks were so keen to rebaptize their Latin cousins. It is tempting to see rebaptism as symptomatic of more ethereal theological topics, in which the perceived differences between the two churches was sufficiently great that the Greek clergy (or at least a subset of them) felt the need to mark the reception of these “converts” from heresy by means of the administration of the sacrament. Certainly this understanding had precedent: as early as 325, the canons of the First Council of Nicaea mandated the reception of Paulianists, who were nontrinitarians, by means of baptism. But I think that this understanding is a mistake with reference to the Latin/Greek conflict. Especially in its earlier phase, in the 11th century, there was no general sense of lasting division: the Greeks generally viewed the Latins as wayward brethren to be corrected, not as heretics utterly outside of the Church, and therefore rebaptism can’t be understood as a requirement resulting from serious deficiencies in the faith on the scale of nontrinitarianism.

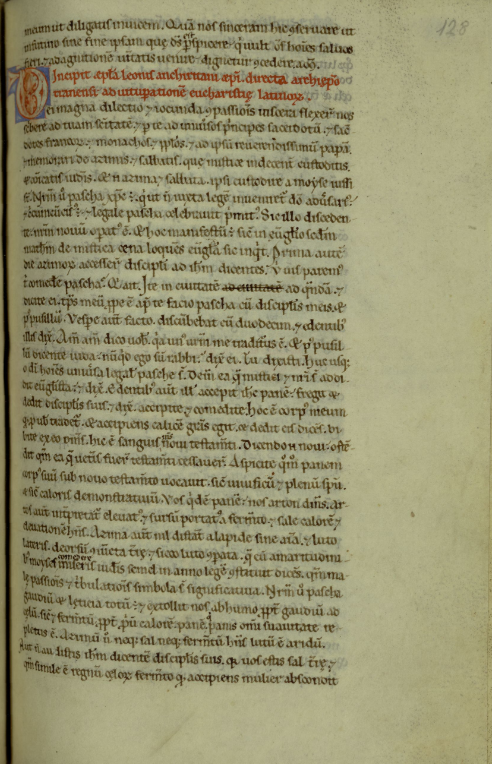

Rather, I think that these rebaptisms were because of perceived ritual deficiencies in the Latin rite of baptism, and particularly, in the idea that the Latins were prone to using a single immersion when administering the sacrament. And when looking at this possibility we find a much greater incidence of Latin complaint and Greek explanation. Shortly after Cardinal Humbert complained about rebaptisms, Michael Cerularius, the Patriarch of Constantinople, wrote to Peter, the Patriarch of Antioch, that the Latins performed baptism with a single immersion [1]. The two centuries that followed saw repetitions of both: Odo of Deuil, Leo Tuscus, an anonymous Dominican author writing from Constantinople in the mid-13th century, and Jerome of Ascoli (i.e., Pope Nicholas IV) all noted that Latin Christians were being rebaptized. The “Byzantine Lists”, a genre of polemic that enumerated liturgical and cultural “errors” committed by the Latins, again and again returned to the notion that the baptism of the Latin rite was performed through a single immersion [2]. In doing so, the authors of these lists were implicitly invoking another of the canons of the early church, this time from the so-called Apostolic Canons (no. 50): “If any Bishop or Priest does not perform three immersions in making one baptism, but only a single immersion […], let him be deposed” [3]

Assuming that my conclusion is correct, that Greeks rebaptized Latins with some degree of frequency because they believed their form of the sacrament to be ritually defective, the question that next arises is how the Greeks came to hold that belief. Prior to the widespread adoption of affusion or aspersion in the Latin West, the form of baptism appears to have been similar to that of the Greek East: a full triune immersion, done together with the invocation of the persons of the Trinity. We see this clearly referenced as late as the early 13th century, when Pope Innocent III, writing to the Maronite Church, instructs them to invoke the Trinity only once “while completing a triple immersion” [4]. The great exception to the standard Latin practice was the famous license given by Pope Gregory the Great to the church in Spain to baptize with a single immersion as a way to signify the oneness of the Trinity and thereby to combat Arianism. This practice was further codified by the 633 Council of Toledo and its existence confirmed in the works of Isidore of Seville and Ildefonsus of Toledo [5]. The practice is referenced twice more, toward the end of the eighth century, in the letters of Alcuin of York, who acknowledged that the practice existed in certain parts of Spain only long enough to condemn the people who baptize in this way as “neglecting to imitate, in baptism, the three-day burial of our Savior” [6]. They maintain this custom, according to Alcuin, “contrary to the universal custom of the holy Church” making Spain the “wet-nurse of schismatics” [7].

Returning, then, to the polemics of the Greeks, is it possible that their complaints about a Latin single-immersion baptism stemmed from the Spanish practice? I see no other possible cause, although this feels unsatisfactory as an explanation. At most, the single-immersion baptism was a regionalism confined to the Iberia, and the opposition of Alcuin, the great champion of Romanization in the West, makes it unlikely that it would ever have spread further than its native peninsula. Indeed, the gradual imposition of the Roman rite throughout the Christian West likely reduced the frequency of single-immersion baptisms within Spain itself in the centuries following the initial permission of Pope Gregory. If the practice survived at all by the mid-11th century, when Cardinal Humbert and Patriarch Michael wrote their respective complaints – and I haven’t found any evidence from that time for or against – it would probably have been a very rare indeed for someone baptized “incorrectly” to have been found in Constantinople.

Pending further evidence, then, we are left with the Greeks reacting at most to an improbability, and more likely to outdated information. While I fully acknowledge that it’s no more than supposition on my part, my best guess is that the works either of Gregory the Great or of Isidore of Seville (or of both, or of someone else entirely) were received in the theological circles of 11th-century Constantinople, leaving the mistaken impression that the practice of single immersion baptism was common in the West. From there, the notion that the Latins performed this sacrament incorrectly, along with most of the others, proved hard to dislodge.

Nick Kamas

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

- Cornelius Will, ed., Acta et Scripta quae de controversiis ecclesiae graecae et latinae saeculo undecimo composita extant (Leipzig: N. G. Elwert, 1861), 153 (Humbert) and 182 (Michael).

- Tia M. Kolbaba, The Byzantine Lists: Errors of the Latins (Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2000), 192.

- The Rudder, trans. Ralph Masterjohn (West Brookfield, Massachusetts: The Orthodox Christian Educational Society, 2005), 179.

- “in trina immersione unica tantum fiat invocatio Trinitatis”. No. 216. Acta Innocentii III, ed. P. Theodosius Haluščynskyj (Vatican, Typis Polyglottis, 1944), 458.

- J.D.C. Fisher, Christian Initiation, Baptism in the Medieval West (London: S.P.C.K., 1965), 91.

- “triduanamque nostri salvatoris sepulturam in baptismo imitari neglegentes”. Ep. 139. Ed. Ernest Duemmler, MGH Epp. 4 (Berlin: Weidmannos, 1895), 221.

- “[…] Hispania – quae olim tyrannorum nutrix fuit, nun vero scismaticorum – contra universalem sanctae ecclesiae consuetudinem […].” “Adfirmant enim quidam sub invocatione sanctae Trinitatis unam esse mersionem agendam.” Ep. 137. Ibid., 212.