Since moving to England, I’ve become very fond of gin, and the medievalist in me was thrilled when I was recently gifted a bottle of Ad Gefrin Distillery’s Thirlings Dry Gin. The gin is inspired by Northumbria’s Anglo-Saxon roots, what Ad Gefrin describes as “a time of welcome, celebration, and hospitality,” and it has been crafted with “a Northumbrian heart and Anglo-Saxon soul.”[1]

The gin is gorgeous, both in its presentation and its finish. The bottle itself embodies the location’s Anglo-Saxon heritage: “Far from just being a vessel for the spirit, the bottle tells its own authentic story. The stepped punt reflects the 7th Century wooden Grandstand discovered on the ancient site and the holes/dimples in the glass represent the post holes which identified where the royal complex of buildings were and enabled archaeologists to calculate their size and height.”[2] Its botanical profile is comprised of “flavours inspired by Northumberland, heather and pine from the Cheviot hills, elderberry and dill from the hedgerows, and Irish moss and sea buckthorn from the coast.”[3] But the base of all gins, of course, is juniper.

Juniper, a type of coniferous evergreen, is native to various parts of the northern hemisphere. There are approximately 30 species, but the common European species, Juniperus communis, is described as “a hardy spreading shrub or low tree, having awl-shaped prickly leaves and bluish-black or purple berries, with a pungent taste.”[4] These berries form the base of gin’s distinctive botanical flavor, which the Craft Gin Club aptly describes as “[r]esinous, piney and fresh on the palate and nose.”[5]

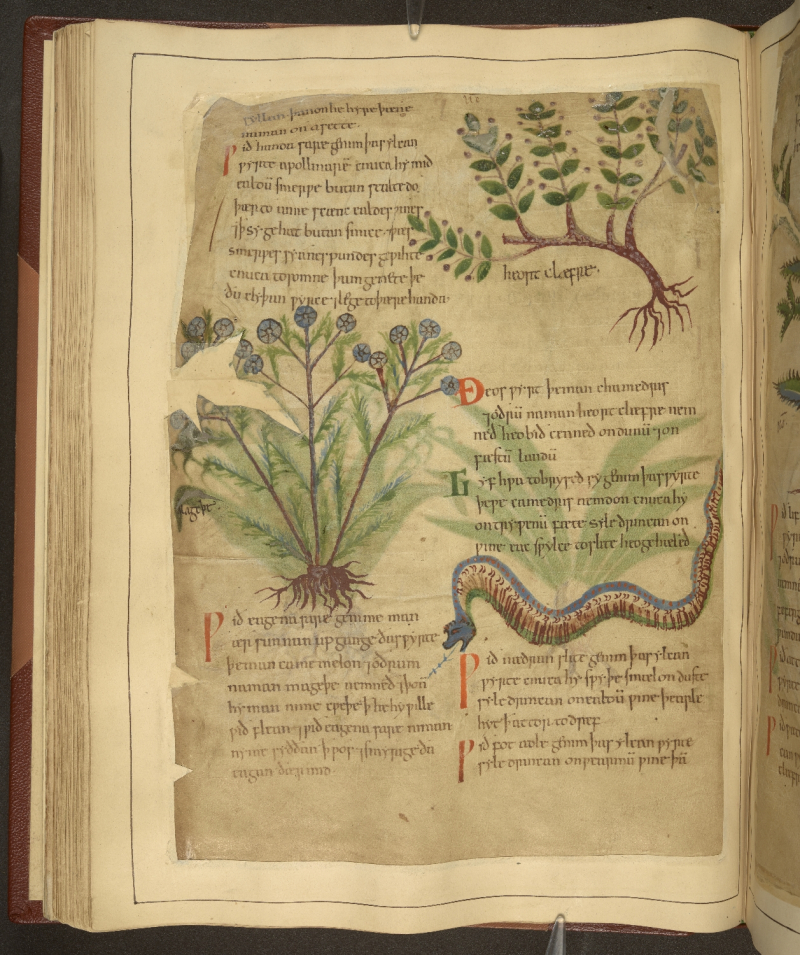

The Anglo-Saxons recognized juniper primarily for its medicinal properties. Its Old English name was cwic-beam, which literally translates to “life-tree.”[6] In the Old English Herbarium, a popular medieval treatise dedicated to the identification and application of plants, juniper is listed as sabine or savine in accordance with its Latin name, Juniperus sabina. As a compilation and translation of originally separate Latin treatises, the Herbarium employs Latin alongside English, much in the same way modern medical textbooks maintain Latin terminology for conditions that are then described in English.

The treatise indicates that juniper can be used to treat “painful joints and foot swelling,” “headache,” and “carbuncles.”[7] In the first instance, the treatise advises that the plant be concocted into a drink; the entry reads: “For the king’s disease, which is called aurignem in Latin and means painful joints and foot swelling in our language, take this plant, which is called sabinam, and by another name like it, savine, give it to drink with honey. It will relieve the pain. It does the same thing mixed with wine.”[8] Here, the king’s disease – in Old English, “wiþ þa cynelican adle”– likely refers to jaundice related to gout.[9] For the treatment of headache, the plant was to be mixed into a kind of poultice and applied to the head and temples.[10] In the case of carbuncles, which refer to a cluster of boils, the plant would be made into a honey-based salve and applied to the infected area.[11]

While juniper was available to the Anglo-Saxons, even in drinking form, distilling was not. In fact, distilled liquors were virtually unknown in medieval England.[12] Rather than spirits, the early medieval English drank beer and mead.

According to John Burnett, “Beer was probably the first drink deliberately made by man.”[13] In his book, Liquid Pleasures: A Social History of Drinks in Modern Britain, Burnett explains that beer brewed from fermented barley has been recorded as far back as the third millennium B.C. in the Bronze Age civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia, and beer production became common across Europe during the Celtic Iron Age.[14] In its earliest use, the Old English beor, “beer,” likely referred to any type of alcohol produced through fermentation, though it appears have been distinct from the less frequently used ealu, “ale.”[15] Beor may have referred to drinks brewed from malt, while ealu may have been a sweeter and stronger drink.[16] These terms may also have been used interchangeably until hops were introduced much later in the medieval period.[17]

The introduction of hops to the brewing process distinguished ale from beer; it also displaced women as the primary producers of the beverage. As A. Lynn Martin explains, “In England ale brewing was a domestic industry dominated by alewives. Their brew was usually sweet, sometimes flavored with herbs and spices, and spoiled if not consumed within several days. The addition of hops created a bitter drink that was stronger and lasted longer than ale.”[18]

Mead, however, was the predominant drink of the Anglo-Saxons and was made by fermenting a mixture of honey and water. The Old English word for “mead” is the same for “meadow”: medu, effectively evoking the beverage’s connection to the flowers and bees essential for the production of honey and, in turn, mead. The plant now known as meadowsweet, or medu-wyrt in Old English, was also sometimes used to flavor the drink.[19]

Additionally, the Anglo-Saxon hall was commonly called the medu-hall, or “mead hall,” indicating not only a primary attribute of the hall but also the centrality of the drink to Anglo-Saxon culture. The hall was an integral part of early medieval English society and functioned as a space for social and political discourse, as well as communal gatherings and feasting celebrations. Indeed, the speaker of the Old English elegy known as The Seafarer describes his loneliness in relation to the absent sounds of the hall, which function as a synecdoche for the communal bonds he craves: “A seagull singing instead of men laughing, / A mew’s music instead of meadhall drinking.”[20]

Because honey was used for a variety of purposes, including the making of both mead and medicine, beekeeping was also an important part of Anglo-Saxon society. In fact, sugar was not produced in medieval England, so honey was the primary sweetener, which is why it appears so frequently in culinary and medical recipes alike. The Old English “Charm for a Swarm of Bees,” a metrical incantation, serves as evidence of honey’s necessity. Essentially, the charm is a magic spell meant to entice a swarm of bees to a keeper and encourage them to remain:

Charm for a Swarm of Bees

For a swarm of bees, take earth and throw it down with your right

hand under your right foot, saying:

I catch it under foot—under foot I find it.

Look! Earth has power over all creatures,

Over grudges, over malice, over evil rites,

Over even the mighty, slanderous tongue of man.

Afterwards as they swarm, throw earth over them, saying:

Settle down, little victory-women, down on earth—

Stay home, never fly wild to the woods.

Be wise and mindful of my benefit,

As every man remembers his hearth and home,

His life and land, his meat and drink.[21]

Eventually, mead went by the wayside, and wine became the more popular drink near the end of the Anglo-Saxon period – at least among the wealthy. As Burnett points out, while the consumption of wine was relatively high throughout the Middle Ages, “it never rivalled beer as the drink of the masses.”[22]

By the 16th century, distilled drinks were “beginning to be served together with sweetmeats at the end of banquets as pleasurable, stimulating aids to digestion.”[23] Distillation describes the process of heating a liquid into a vapor, which is then condensed into a pure essence, and the procedure may have been known to the Chinese as early as 1,000 B.C.[24] Burnett explains that the “the requisite knowledge was brought to the West either by the Cathars or by returning Crusaders, who had seen distillation practised by Arab alchemists. A coded recipe for ‘aqua ardens’ appeared in a French monastic tract about 1190 alongside one for artificial gold, and through the medieval world spirits were regarded as mysterious, even magical, substances, used only medicinally for their stimulating, reviving qualities.”[25]

He continues: “English records of ‘aqua vitae’ distilled from wine appear in the fourteenth century, when it was made by monks and apothecaries, and became more widely known during the Black Death (1348-9) as a warming prophylactic. Spirits were also redistilled with herbs and flowers from the physic gardens of monasteries to make a variety of liqueurs with therapeutic properties, while in private households spirit-based ‘cordials’ were recommended for the treatment of palsey, the plague, smallpox, apoplexy, ague and other diseases.”[26]

Gin, from the Dutch genever, or “juniper,” because it was distilled with the plant’s berries, started being imported into England from the Netherlands during the late 16th century. The original product was “a highly flavoured, aromatic drink” that is still produced in the Netherlands and typically enjoyed neat.[27] By the mid-18th century, however, England had begun producing its own version in London, which was “less coarse and more subtly flavoured.”[28] By this time, spirits were being consumed largely for pleasurable, rather than medicinal, purposes.

While gin and distillation were not known to the Anglo-Saxons, juniper certainly was, and in this way, the spirit’s botanical roots are intertwined with medieval English history.

Emily McLemore, Ph.D.

Alumni Contributor, Department of English

Lecturer, Bishop Grosseteste University (U.K.)

[1] Ad Gefrin, https://adgefrin.co.uk/spirits/gin. Special thanks to Chris Ferguson and Claire Byers from Ad Gefrin for supplying additional information and wonderful photos.

[2] Ad Gefrin, https://adgefrin.co.uk/spirits/gin.

[3] Ad Gefrin, https://adgefrin.co.uk/spirits/gin.

[4] “juniper,” Oxford English Dictionary.

[5] Craft Gin Club, “The Gin Herbarium: A Guide to Herbal Gin Botanicals!,” https://www.craftginclub.co.uk/ginnedmagazine/guide-gin-herb-botanicals.

[6] “cwic-beam,” Bosworth Toller’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.

[7] Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Early Medieval Medicine, Routledge (2023), p. 113.

[8] Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies, p. 165.

[9] Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies, p. 165.

[10] Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies, p. 165.

[11] Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies, p. 165.

[12] William Edward Mead, The English Medieval Feast, Routledge (2019), p. 123.

[13] John Burnett, Liquid Pleasures: A Social History of Drinks in Modern Britain, Routledge (1999), p. 112.

[14] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 112.

[15] “beer,” Oxford English Dictionary.

[16] “ale,” Oxford English Dictionary.

[17] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 112.

[18] A. Lynn Martin, Alcohol, Sex, and Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Palgrave (2001), p. 7.

[19] Emma Kay, Fodder and Drincan: Anglo-Saxon Culinary History, Marion Boyars Publishers, Ltd. (2023), p. 153.

[20] Craig Williamson (translator), The Complete Old English Poems, University of Pennsylvania Press (2017), p. 468.

[21] Williamson (translator), The Complete Old English Poems, p. 1081.

[22] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 142.

[23] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 160.

[24] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 160.

[25] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 160.

[26] Burnett, Liquid Pleasures, p. 160.

[27] “gin,” Oxford English Dictionary.

[28] “gin,” Oxford English Dictionary.