As a continuation of sorts to my last post, on Peter Damiani’s reaction to the events of 1054, I’ve decided to take a look at another churchman writing on the same topic a few years later, a certain Laycus of Amalfi, who undertook to compose a defense of the use of unleavened bread (azymes) in the Eucharist around the year 1070 [1]. His work took the form of a letter, addressed to Sergius, a Latin-rite abbot living in Constantinople. According to the text, Laycus had been motivated to write by reports from his correspondent and from other Latins that they had been completely surrounded by those who were trying to persuade them to abandon the Latin liturgical usage in favor of the Greek [2].

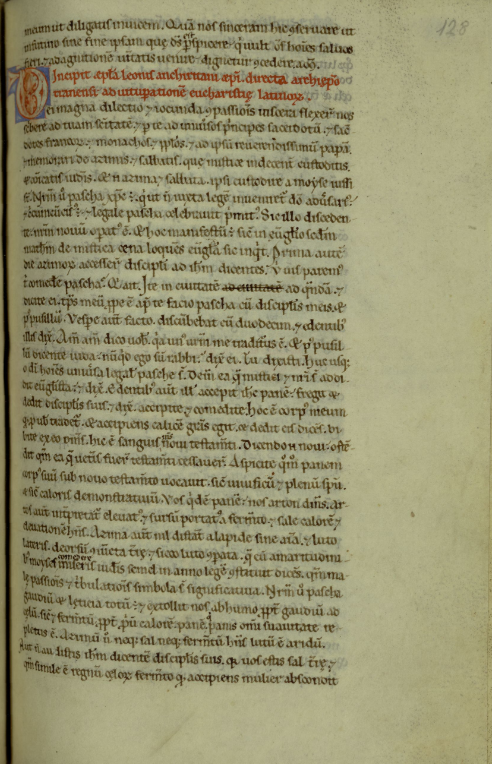

Other than his name, virtually nothing else is known about the author of the text. The sole surviving manuscript witness (Brussels, Bibliothèque royale 1360 / 9706-25, 116v-119r) gives only the identification “a letter of Laycus, cleric” (“epistola layci clerici”), a seeming contradiction in terms that leaves us with the assumption that “Laycus” is a given name. Anton Michel, who edited the text in 1939, notes further that monastics of the time tended to identify themselves as such: the absence of a word like “frater” in self-reference suggests that the author was not in monastic orders [3]. Even the origins of the author in the city of Amalfi are conjectural, and they are based more on his presumed links to Abbot Sergius, who was likely the leader of the monastery of St. Mary of the Amalfitans in Constantinople, an establishment attested by Peter Damiani around the same time[4].

The manuscript that preserves this text is also one of the few early copies of the work of Humbert, Cardinal of Silva Candida, and, as it happens, it is from Humbert’s writings that our Laycus drew most of his arguments in favor of the azymes. The core argument, in Laycus as in Humbert, was an appeal to the example set by Christ at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. According to the argument, Christ, who came to fulfill the Law of Moses, would have used unleavened bread at the Last Supper since the synoptic Gospel accounts place the event on the first day of the celebration of Pascha (Pesach), when leavened bread was prohibited in observant Jewish households. This act of institution was reinforced during the supper at Emmaus, which likewise occurred during the days of Pascha and is regarded in the text as a celebration of the Eucharist [5]. This practice was preserved by the Roman Church, according to Laycus, who cited Popes Anacletus, Clemens, and Sylvester as uniquely instrumental in this effort [6].

Especially for the period of the pre-Gregorian Reform, the tone of the text is fairly mild. The introductory paragraphs make reference to the “most pious, holy, and wise fathers and doctors [of the Greeks]” who themselves used leavened bread in the Eucharist (but who didn’t, though, attack the Latin use) [7]. And the letter of Laycus appears all the more gentle in comparison with the source material: gone is the spirited, “listen up, stupid” (“audi, stulte”) style of invective found in Cardinal Humbert [8]. Instead, we find almost a plea to avoid rending the garment of Christ by provoking division between the two rites, coupled with an emphatic statement that the one faith could contain various customs within the churches [9].

Does the work of Laycus of Amalfi change our understanding of the azyme debate or the conflict between the Eastern and Western churches more broadly? In terms of theological content, to put it bluntly, not really. The arguments advanced by Laycus were the same as those put forward by Humbert some fifteen years prior, and, while the text written by Laycus was itself copied by Bruno of Segni in another epistle in the early twelfth century, this branch of the post-Humbertine literary tradition does not leave any substantial mark in the theological framework of the Latin church. On the other hand, the very existence of this letter, along with the fact that a Greek prelate took the time to respond to it, does indeed broaden our insight into the East-West conflict more generally [10]. It emphasizes, first of all, that the Humbertine legation in 1054 was not a one-off attempt to open lines of communication between the two churches. Rather, communication was happening, even without the intervention of popes and patriarchs, and it was based on pre-existing and well-established ties connecting East and West. A Latin-rite monastery in Constantinople, staffed by Amalfitans, would naturally be in contact with friends, relatives, and fellow clerics back home.

Second, to return to a point that I’ve made before, this letter makes clear that there was no general sense of schism between East and West in the aftermath of the 1054 legation. Indeed, as noted above, the tone of this letter is notably more civil than the polemics of Humbert. Although Laycus was certainly more of an azyme partisan than was Peter Damiani, the work and its date of composition points to an extended window in which ecumenical dialogue, in the sense that both sides still saw each other as part of the same community, was still possible.

Nick Kamas

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

- Anton Michel has published the only substantial scholarly treatment of the material and the only edition of the text. Amalfi und Jerusalem im Griechischen Kirchenstreit (1054–1090): Kardinal Humbert, Laycus von Amalfi, Niketas Stethatos, Symeon II. von Jerusalem und Bruno von Segni über die Azymen (Rome: Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1939. See also a short summary in Jonathan Shepard, “Knowledge of the West in Byzantine Sources, c.900–c.1200” in A Companion to Byzantium and the West, 900-1204, ed. Nicolas Drocourt and Sebastian Kolditz (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 67.

- Laycus of Amalfi, c. 1, Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 35.

- Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 21.

- Peter Damani, Letter 131, trans. Owen J. Blum, The Letters of Peter Damian Peter Damian, Vol. 5, Letters 121–150, The Fathers of the Church: Medieval Continuation 6, (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2004), 55. For an assessment on why this monastic house in particular, see Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 18–19.

- Laycus of Amalfi, c. 5–11, Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 37–42.

- Laycus of Amalfi, c. 14–15, Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 44–45.

- Laycus of Amalfi, c. 2, Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 36. “Licet illorum [Graecorum] religiosissimi, sanctissimi atque sapientissimi patres ac doctores fuerint et studuerint ex fermentato pane omnipotenti domino sacrificium offerre, tamen numquam invenimus illos nostram oblationem evacuantes aut deridentes […].”

- Humbert, Cardinal of Silva Candida, Responsio sive Contradictio adversus Nicetae Pectorati Libellum, cap. 13, edited in Cornelius Will, Acta et Scripta quae de controversiis ecclesiae graecae et latinae saeculo undecimo composita extant (Leipzig: N. G. Elwert, 1861), 141.

- Laycus of Amalfi, c. 3, Michel, 36–37. “Numquid divisus est dominus in corpore suo, ut alius sit Ihesus Christus in Romano sacrificio, alius in Constantinopolitano? Quis hoc orthodoxus dixerit nisi ille, qui dominicam non veretur scindere vestem? Nos veraciter tenemus, immo firmiter credimus, quia, quamvis diversi mores ęcclesiarum, una est tamen fides […].”

- Probably Symeon II of Jerusalem. Michel, Amalfi und Jerusalem, 25–28.