Last week, I surveyed Chaucer’s representations of prison spaces throughout his corpus. Today, I consider one reader of Chaucer, for whom those images of imprisonment would have particularly resonated.

In January of 1549, John Harington of Stepney and Kelston was arrested and sent to the Tower of London.[1] Harington remained in the Tower with his master, Thomas Seymour (the brother of Henry VIII’s third wife, Jane) for more than a year.[2] What was a literary-minded gentleman/prisoner to do with all of that time? Harington may have read Chaucer.

Harington was in the Tower following suspicion about the nature of Seymour’s relationship with the very young Princess Elizabeth. He was also questioned regarding his own role in setting up a marriage between Lady Jane Grey, the nine-days queen, and the young King Edward VI.[3]

While in the Tower, Harington would have had access to books and illustrious, scholarly-minded company. The imprisoned Harington used this time to learn French, and he wrote a translation of Cicero’s De Amicitia.[4] As he told Lady Catherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, in the dedication to his translation:

Wherby I tried prisonment of the body, to be the libertee of spirite … and in the ende quietnes of mind, the occasion of study. [5]

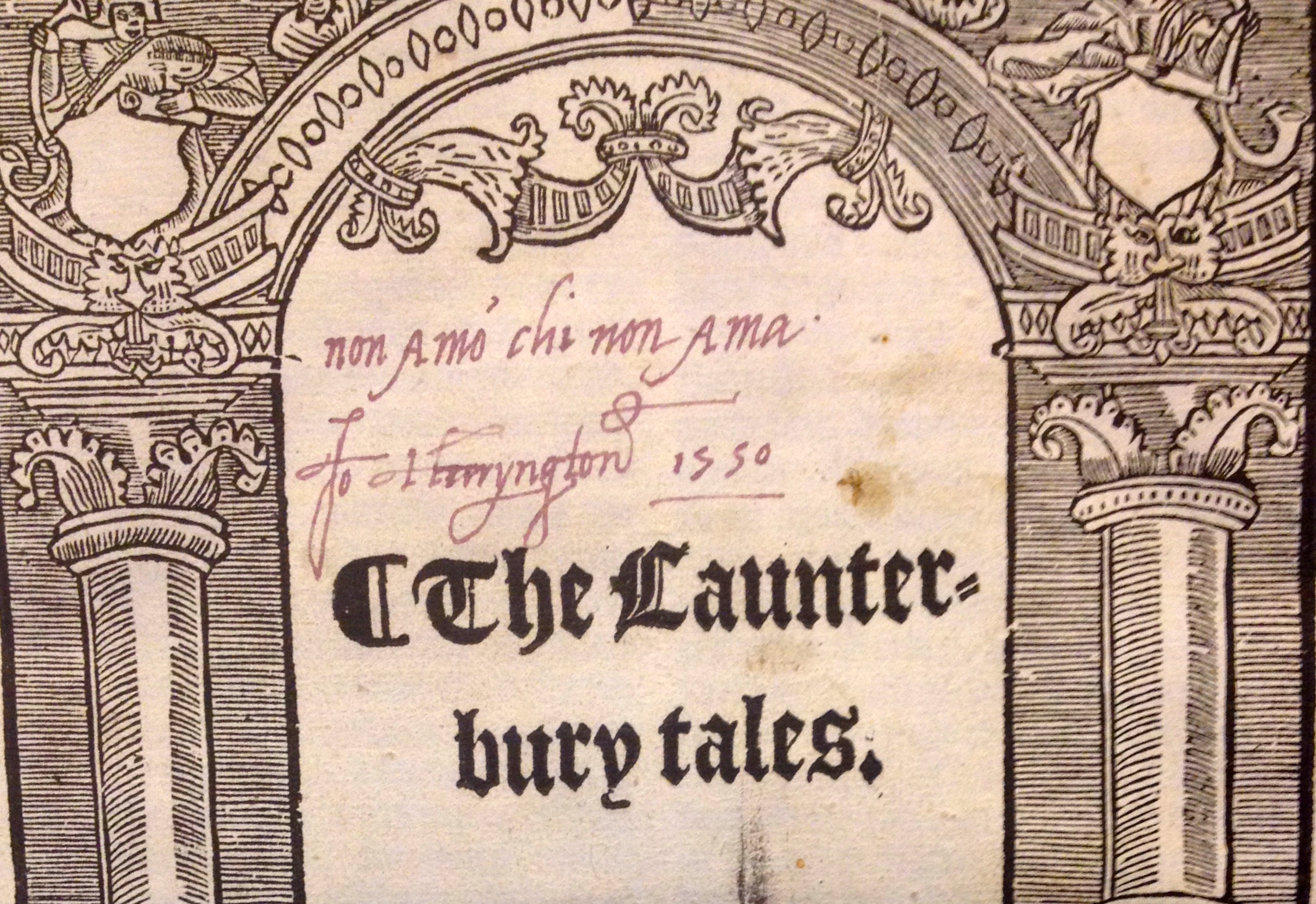

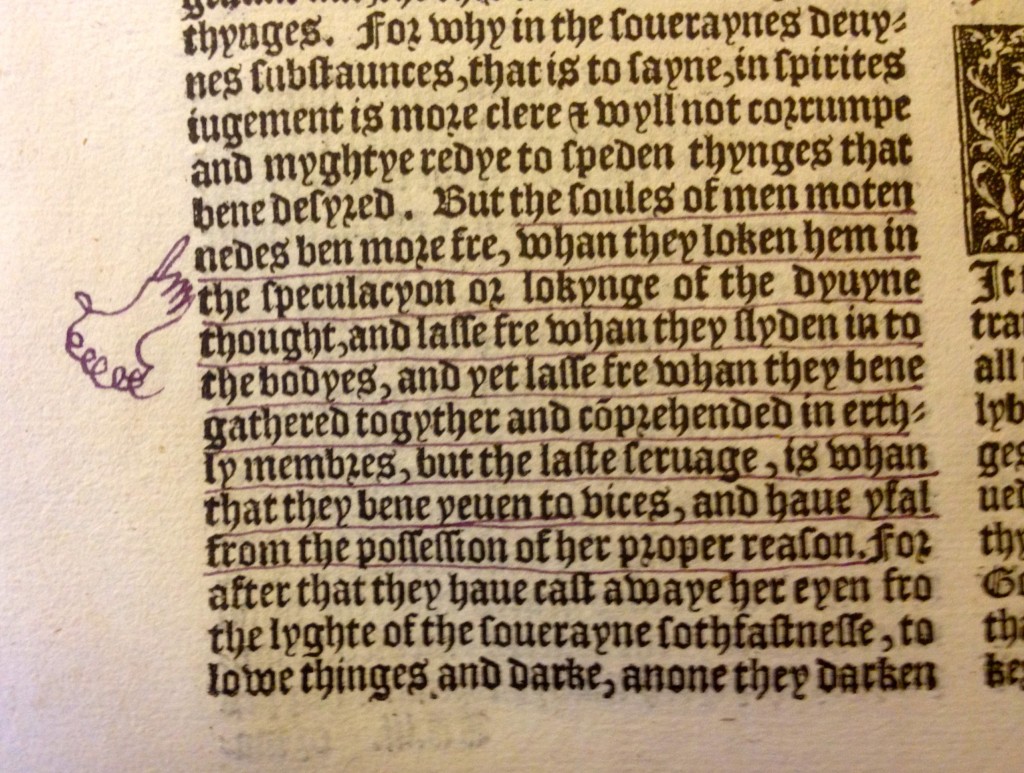

Though the 1550 date on the front of Harington’s copy of Chaucer is not definitive evidence that he held the book while he was in the Tower, the long and idle days of imprisonment would haven given Harington the time he needed to thoroughly annotate his copy of William Thynne’s 1542 edition of Chaucer’s complete works. Harington’s copy is now housed at the University of Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Library.[6]

Nearly every page of the 1542 book shows evidence of Harington’s attentive reading. This post, of course, cannot cover everything involved in Harington’s copious marginal writing, but if readers are interested, they can consult my more detailed article — “Reading Chaucer in the Tower: The Person Behind the Pen in an Early-Modern Copy of Chaucer’s Works” — forthcoming in The Journal of the Early Book Society, volume 18.

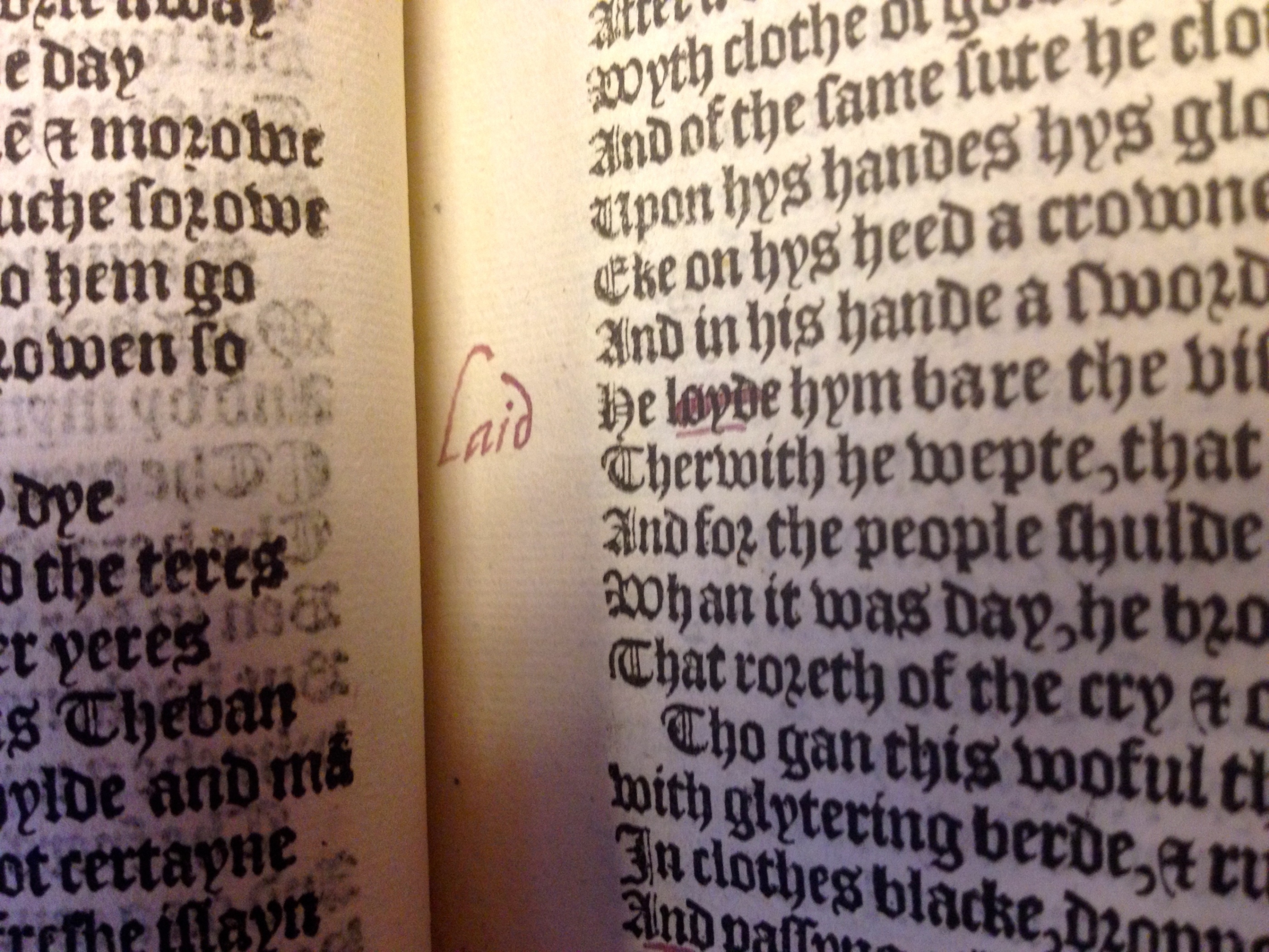

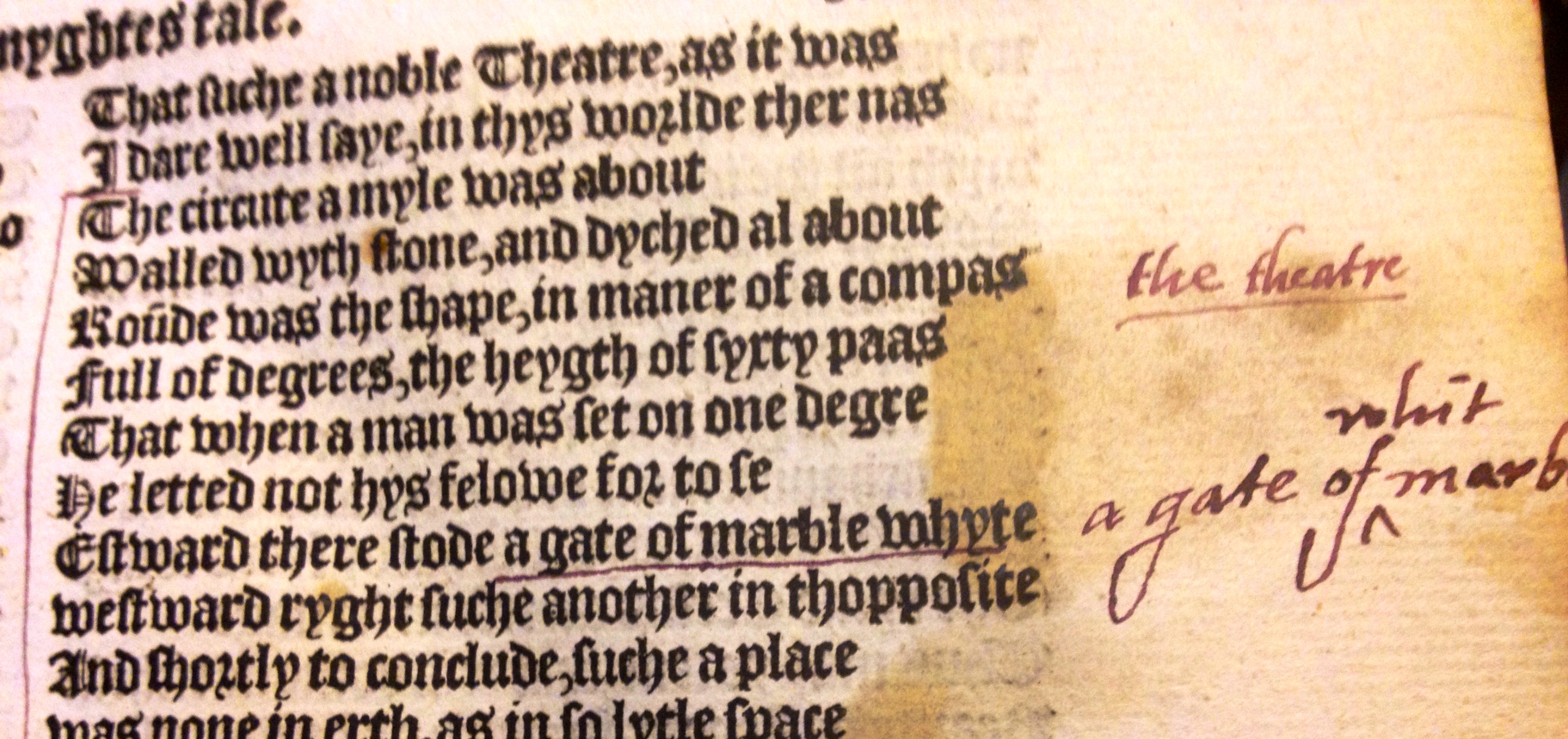

One of Harington’s key concerns throughout was correcting ‘errors’ where he saw them in his book. He ‘corrects,’ or modernizes, spelling and adds commas or other marks of punctuation where he finds them appropriate.

Though these meticulous changes may make Harington seem a bit finicky, they reveal how closely he paid attention to every word on the page. He desired to improve his book, certainly an indication that he valued Chaucer.

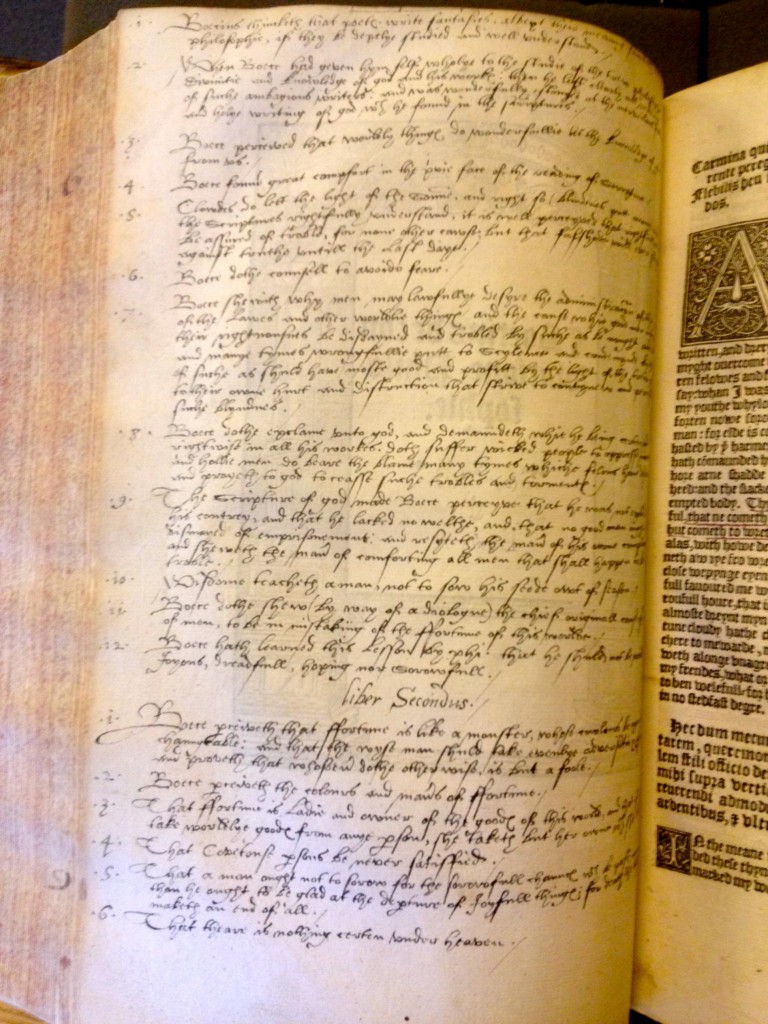

However, his annotations are much more extensive than simple summary notes and spelling changes. Of particular interest to Harington was Chaucer’s Boece, a translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. A full-page table of contents and summary precedes Boece on a blank verso page, and Harington marginally marks the translation throughout.

That Boethius wrote the Consolation of Philosophy while in prison might have resonated with the imprisoned Harington.[7] The imprisoned gentleman may have found Boethius’s discussions of free will, predestination, and changeable fortunes particularly relevant as he lamented the downturn of his own fortunes in court. Certainly this was the case for the imprisoned King James I of Scotland when he wrote his prison poem The Kingis Quair, which drew on Boethius.[8]

Overall, Harington, who also occasionally wrote his own poetry, was an attentive reader, finding solace in careful study. He was meticulous, academic, and thorough in his annotations, but, it would seem, he was also attentive to the book’s correspondences with his own life and experience.

Mimi Ensley

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Footnotes

1. Ruth Willard Hughey, John Harington of Stepney: Tudor gentleman (Columbus, OH: Ohio State UP, 1971), 28.

2. Ibid., 29-30.

3. Ibid., 22-4. See also Harington’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12325

4. Ibid., 31-2.

5. John Harington, “The booke of freendeship of Marcus Tullie Cicero,” in Hughey, John Harington, 137.

6. Geoffrey Chaucer, The Workes, Newlye Printed: Wyth Dyuers Workes Whych Were Neuer in Print Before, ed. William Thynne (London, 1542).

7. For a similar suggestion, see the brief description of Notre Dame’s 1542 Thynne edition here: http://rarebooks.library.nd.edu/exhibits/fructus/middle_english/1542chaucer.html

8. http://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/mooney-and-arn-kingis-quair-and-other-prison-poems-kingis-quair-introduction