In my most recent post, I discussed some conflicting issues between different types of quantitative source material on late medieval confession and confessors. There I argued that historians of late medieval religious life have mischaracterized the popularity and volume of confessional manuals as a denunciation of the capabilities and efficacy of late medieval confessors. As an alternative, I offered the huge number of requests, known as supplications, to the papacy for new confessors in the fifteenth century. These supplications show popular enthusiasm by the laity across all Western Christendom for personal confessors.

While there are almost 14,000 surviving supplications to the papacy for a new confessor, these requests were not distributed evenly. From my previous post, one can see that supplications from France account for over 50 percent of the source material. If we examine the supplications categorized by those historians as “French”, we see another interesting numerical imbalance:

| Burgundian Total (Reg. Mat. Div. 1-41)[i] | 1442 |

| 1409-1411 | 15 |

| Eugenius IV, (1431-1447) | 181 |

| Nicholas V, 1447-1455) | N/A |

| Calixtus III (1455-1458) | 227 |

| Pius II (1458-1464) | 233 |

| Paul II (1464-1471) | 364 |

| Sixtus 1471-1484 | 319 |

| Innocent VIII (1484-1492) | 118 |

The supplications from late medieval Burgundy, categorized as French due to current geographical boundaries by modern historians, account for 20.2 percent of French entries.

When we consider population estimates, a notoriously difficult issue to tackle, the proportion of Burgundian supplications proves even more striking. In 1450, the estimated population of French lands, including late medieval Burgundy, was around twelve million people.[ii] The estimated population of Burgundy, according to tax data collected from the same period, was 1.4 million people.[iii] Some quick math tells us that the Burgundian population made up about 11.6 percent of the larger French population.

As we can see by comparing the discrepancy in Burgundian-French supplications to the Burgundian-French population, there is a net difference of 8.6 percent between the two categories. Based on this information, we see that the people of late medieval Burgundy were more likely to request a personal confessor than population estimates would suggest. Indeed, Burgundian supplications make up a little more than 12 percent of all supplications to the papacy in the fifteenth century, although they account for around 4 percent of the population of Western Europe at the time.

The sheer amount of supplications coming from Burgundian lands begs the question as to why the people of Burgundy had such a disproportionate enthusiasm for the personal confessor. One potential explanation comes from the political realities of late medieval Burgundy, specifically the idea of representation by the more well-to-do citizens of Flemish cities.

The Flemish cities were, by far, the most populous lands within Burgundy, and had a long history of fighting and revolting against the Dukes of Burgundy for political representation and rights.[iv] These revolts happened so frequently that historians have gathered them into a distinct category called the fourth period of Flemish urban rebellions (1379-1453). Within this period, the people of Gent revolted at least eleven times in the fifteenth century, with the longest and most bitter revolt occurring from 1449 to 1453.

Most interestingly for our purposes here, the revolt of 1449-53 was followed by the largest spike in supplications to the papacy for new confessors both from dioceses in which the revolts occurred, as well as the Burgundian lands in general.[v] In the years that followed the revolt of 1449-53, Burgundian supplications to the penitentiary exploded to 267 requests in a five-year span. Before 1449, there are only 191 requests extant from the entirety of Burgundian dioceses in the first half of the fifteenth century, with 181 of those coming during the sixteen-year papacy of Eugenius IV (1431-1447).

Later revolts in Gent of 1467 and 1487 also saw large upticks in supplications to the papacy, especially the revolt of 1467 against Duke Charles the Bold. 1469 had the highest number of requests for a new confessor out of any year in the fifteenth century with 82.

These Flemish revolts do not conclusively explain the proclivity of the people in Burgundy to seek a new confessor. But they do give us a window into the wider political and social currents, which help to explain Burgundian enthusiasm in these requests, as well as the various upticks in those same requests in the fifteenth century.

Sean Sapp, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

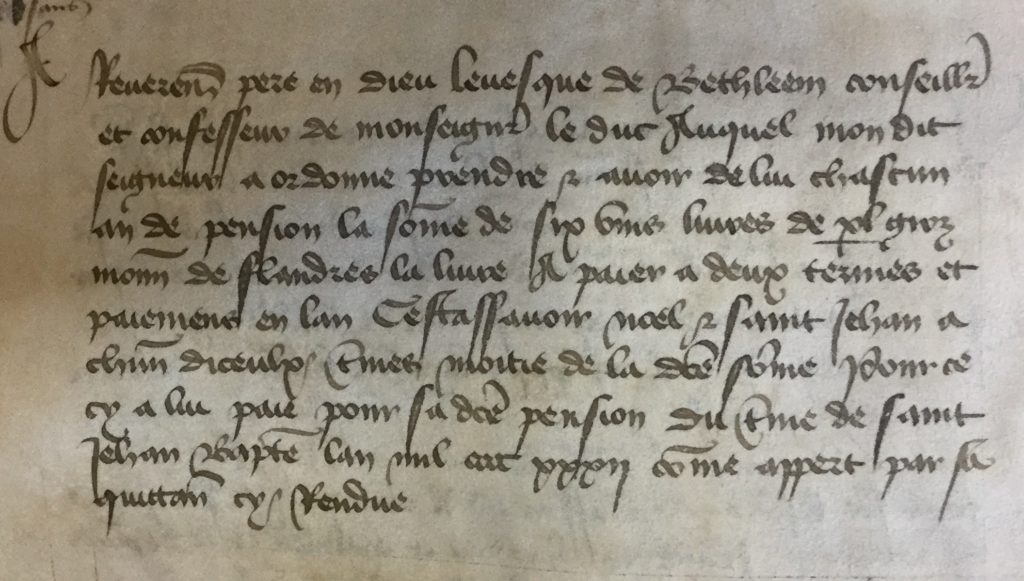

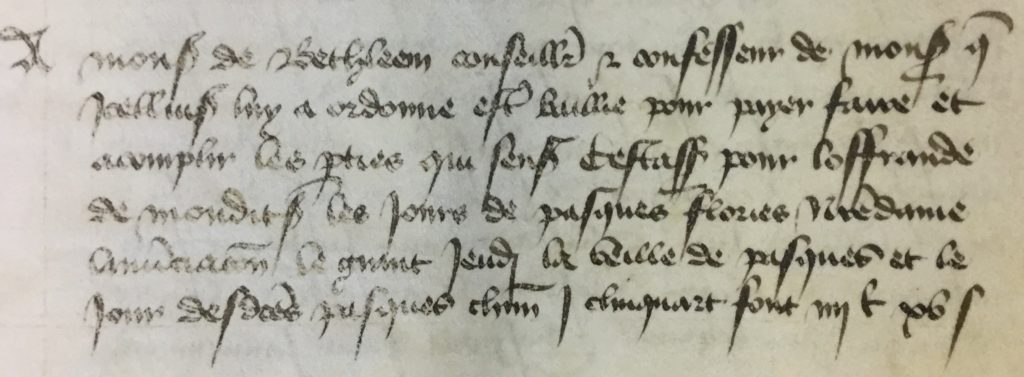

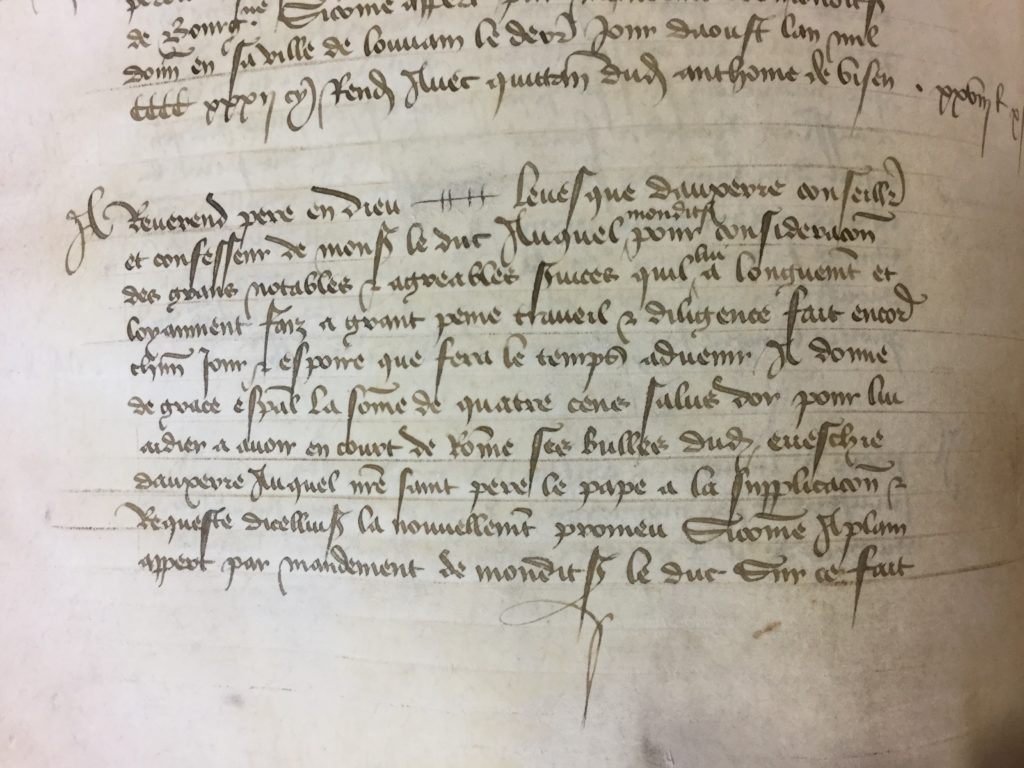

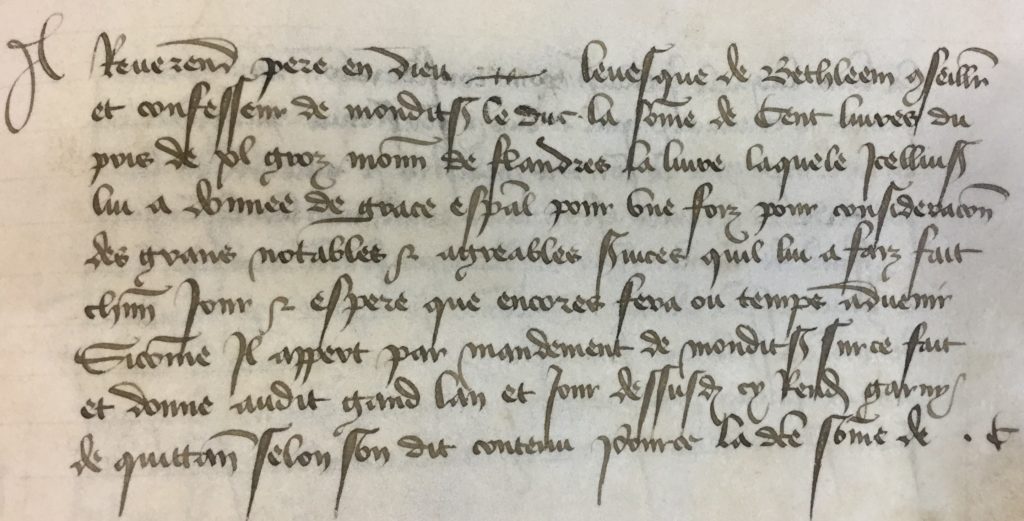

[i] Based upon my own research in the archives of the Apostolic Penitentiary.

[ii] J. C. Russell, “Population in Europe,” in The Fontana Economic History of Europe, Vol. I: The Middle Ages, ed. Carlo M. Cipolla, (Glasgow : Collins/Fontana, 1972), 25-71.

[iii] Norman J. G. Pounds, “Population and Settlement in the Low Countries and Northern France in the Later Middle Ages,” Revue belge de philologie et d’histoire, vol. 49, fasc. 2, 1971. Histoire (depuis l’Antiquité) — Geschiedenis (sedert de Oudheid), 369-402.

[iv] Jan Dumolyn & Jelle Haemers, “Patterns of urban rebellion in medieval Flanders,” Journal of Medieval History, 31:4, (2005), 369-393.

[v] The registers of supplications in the Apostolic Penitentiary are fragmentary or lost for the first quarter of the fifteenth century, so it is unclear if this pattern holds true for the early revolts.