There are few things I like to do more than pouring over an old map. For those working on the Maeander River Valley (modern Büyük Menderes in western Türkiye), we are spoiled by old maps from archaeological surveys and excavations from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike earlier maps, these maps surveyed and composed for archaeological purposes were more detailed and often more accurate in their spatial representation. In this blog, I want to introduce two fascinating maps.

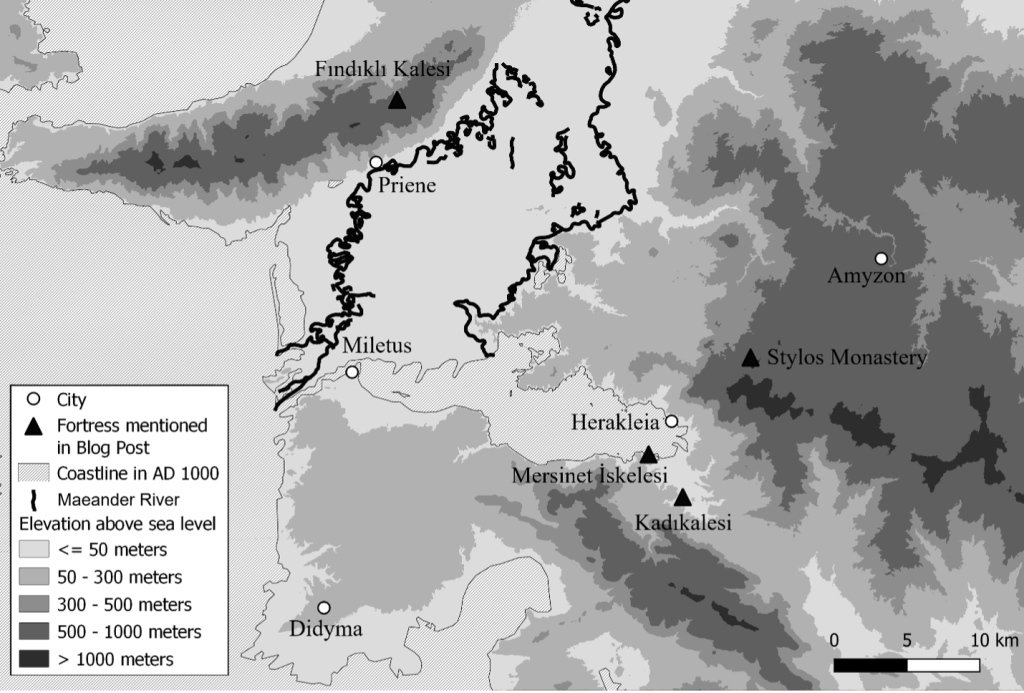

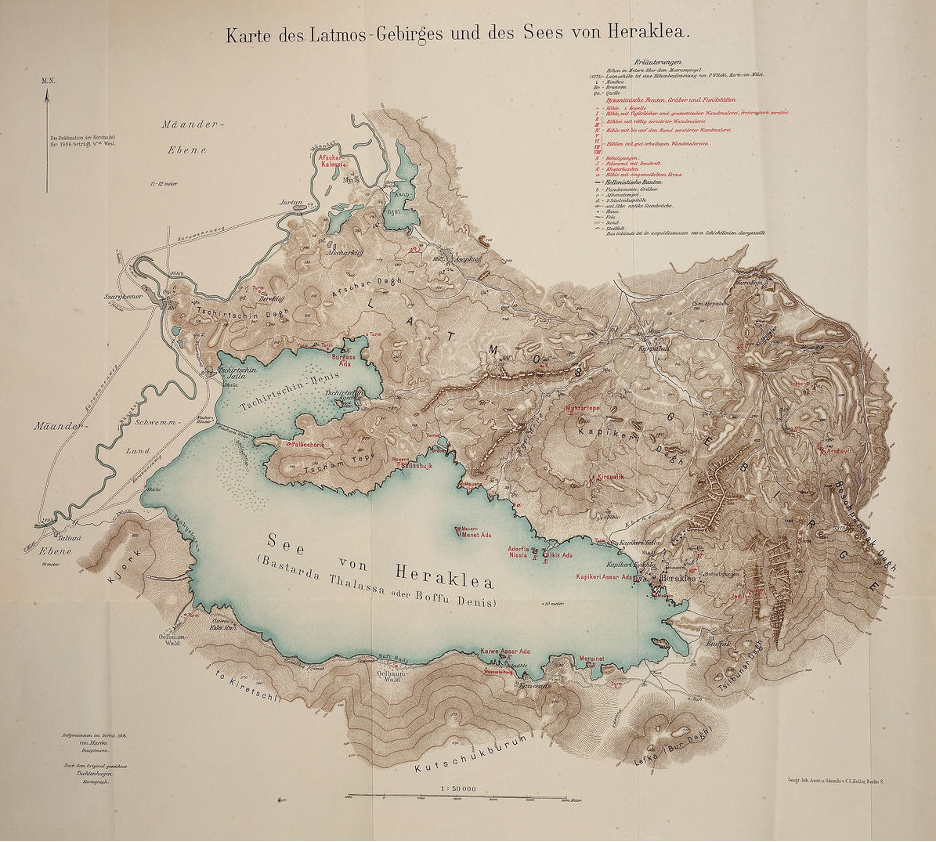

First, is the Lyncker map, named for the military officer Karl Lyncker who carried out the bulk of the investigations around 1908 and 1909. The map was produced for the archaeological exploration and excavations conducted in the valley by Theodor Wiegand. This map is best understood as a composite map, including the map of Lake Bafa by the military officer Walther von Marées in 1906 (Fig. 1) and the map of the Milesian peninsula by the mine surveyor Paul Wilski in 1900 (Fig. 2). Alfred Philippson, a geologist, would conduct his own surveys and produce his own map in 1910 (Fig. 3). Later, Philippson would compile all the earlier maps and publish them as a composite map in 1936 in the series of volumes of the Miletus excavation.[1]

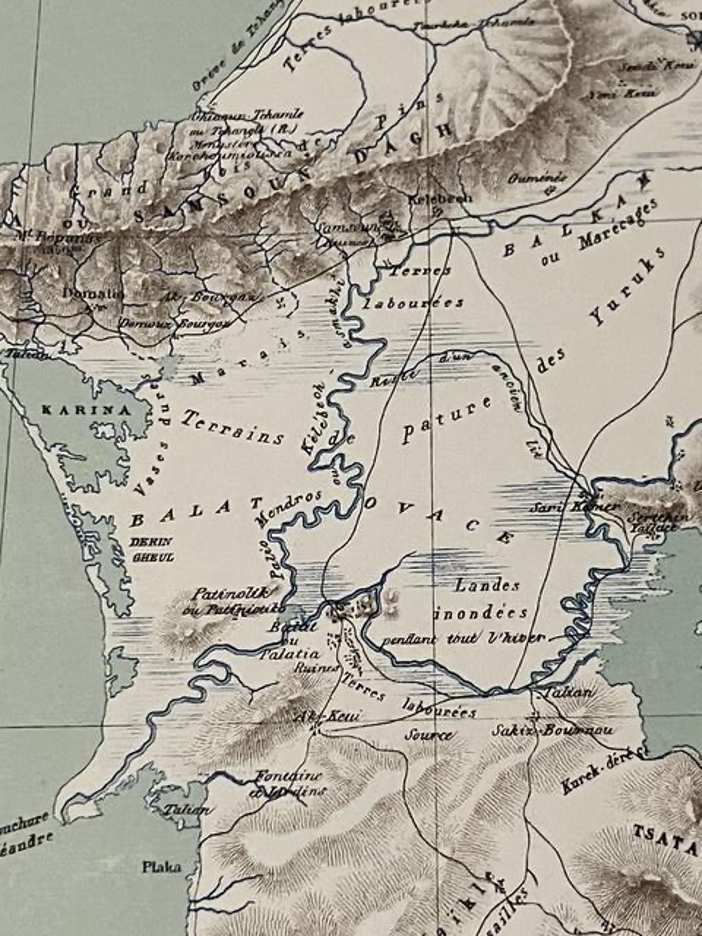

The second map accompanied the archeological work of Olivier Rayet and Albert Thomas and was composed in 1874 (Figs. 4, 5, and 6).[2] While Wiegand outsourced his cartography to professional geodesists, Rayet drew the map himself.

These maps are an important source of ancient and medieval ruins that have since disappeared. However, I have always marveled at what these maps reveal unintentionally: the landscape of the late Ottoman Maeander Valley before a series of changes that would occur in the twentieth century.

Before the Population Exchange of 1923

In 1923, the Greek populations living the Maeander were exchanged with Turkish populations living in Greece. These maps include many Greek toponyms that are no longer used. Didyma is known by its Byzantine name of Hieron (Jeronda), while the town on the southern coast of Lake Bafa was known as Mersinet, a survival of the Byzantine Myrsinos (Fig. 1). The toponym of Patniolik (Figs. 2, 3, and 5), which became the modern Batmaz Tepe (the hill that cannot sink), makes clear that the origin is not Turkish, but Byzantine; this was a village owned by the monastery of Saint John the Theologian on the island of Patmos. On the southern face of Mount Mykale, the ancient site of Priene is still known by its Byzantine name of Samson (Samsoun) on the Rayet map (Fig. 5), while the village of Domatia (Figs. 3 and 5) is likely the survival of the Byzantine toponym Stomata, which references the mouth of the Maeander River.

The town of Bağarasi (Gjaur – Bagharassi on the Lyncker map) missed out having its old Greek name, Mandica, as it was renamed after the Greek War of Independence (1829). Still, not all Greek toponyms imply a direct Byzantine survival. The Greek communities of the late Ottoman period are idiomatic to their time and are not simply the fossils of another era; some immigrated from the islands after the plagues of the seventeenth century, while others moved to the area to work for local Turkish lords (like the Cihanoğlu family in the Turkish town of Koçarlı – there is no reason to assume that the church in Koçarlı in the Lyncker map required a Byzantine predecessor).

Before the Draining of the Büyük Menderes

Beginning in the late 1920’s, a series of drainage canals fundamentally transformed the hydrological realities of the Maeander Valley. Before the construction of this system of canals, the Maeander valley flooded every winter and remained inundated until spring. This could wreak havoc on transportation across the valley and rendered many places in the plain isolated throughout the winter. A rather frustrated Gertrude Bell – a Byzantinist in her own right – who visited the Maeander Valley around the same time as Lyncker, remarked:

“This sort of travelling is far more difficult and less pleasant than my Syrian journeys. There one simply gets onto a horse and rides off, carrying one’s house with one. Here there are so many arrangements to be made and one has to depend on other people’s hospitality which is always a bore. It’s worth doing however and while I am about it, I will see as much of the country as I can so that I need not come back.”[3]

The draining of the valley was not just the construction of individual canals, but the construction of a system of canals that included the entire valley, where the canals, parallel to the river, provided drainage for the entire valley. Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Ottomans all had drainage of some type in the Maeander, but I have seen no evidence of a valley-wide attempt to drain until the early years of the Turkish Republic.[4] One of the clearest representation of these canals as a system is found in a map from a British Naval Intelligence Division geographical handbook from 1943, when this process was well underway but far from finished.[5]

Despite the difficulties of living in the open plain in this period, the Lyncker map shows considerable number of settlements, from the series of houses along the river between Priene and Miletus, to the villages east of the town of Söke (Fig. 3). While the Rayet map is less detailed in showing the late Ottoman settlement pattern, it does often show where the major fields were located (Terres labourées), such as the northeastern extreme of the Milesian peninsula, those directly south of Priene (Fig. 5), and the plain between Söke and Burunköy (Bouroun Keui, Fig. 6). Because marshes are dynamic and seasonal in the Maeander, that these two maps do not show the same regions as swamp makes sense. The Lyncker map is oriented more towards the summer and fall, mapping the lakes found at the center of a swamp, while Rayet shows the much wider area that likely saw itself underwater during the winter and spring. Near Miletus (Balat ou Palatia), Rayet designates “lands flooded during the winter” (Landes inondées pendant tout l’hiber). In fact, this is a consistent problem when examining maps, even into the second half of the twentieth century. What can appear as an invented lake – a “paper lake,” if you will – is instead a cartographer mistaking what is permanent for what is seasonal.

For western Türkiye, the twentieth century introduced a series of fundamental changes to the landscape. Being able to see what the landscape looked like before that can provide important insights about the medieval landscape. But, if I am honest, pouring over these maps is simply just a great way to pass an afternoon!

Tyler Wolford, PhD

Byzantine Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

[1] Alfred Philippson. Das südliche Jonien. Milet III.5. Berlin and Leipzig, 1936.

[2] Olivier Rayet and Albert Thomas. Milet et le Golfe Latmique, Tralles, Magnésie du Méandre, Priène, Milet, Didymes, Héraclée du Latmos: Fouilles et explorations archéologiques. Paris, 1877. This map can be viewed online at http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/rayet1877a/0002.

[3] https://gertrudebell.ncl.ac.uk/l/gb-1-1-1-1-17-19

[4] Süha Göney. Büyük Menderes Bölgesi. Istanbul, 1975, 245-256.

[5] Naval Intelligence Division. Turkey. Volume II. Geographical Handbook Series. 1943, 159.