[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

Though it has gained prominence over the course of the past couple of years, the Alternative Right — commonly known as the “Alt-Right” Movement — was branded in 2008 by Richard Bertrand Spencer, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

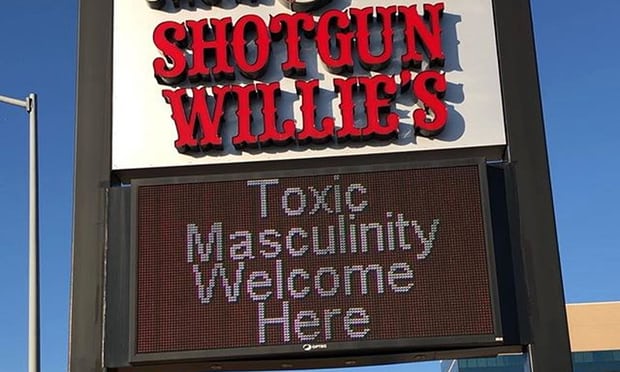

Seeking to appeal to young, often college-aged people, the Alt-Right Movement promotes white supremacy and radical far-right ideals. It rejects mainstream conservatism, and favors extremist politics.

According to an article in The Economist, the Alt-Right primarily promotes its agenda online, through websites such as 4Chan and Reddit. While it often utilizes elements of pop culture, such as memes, to advance its ideas, as of late, the movement has also employed a much older tool to defend its tenets: medieval history.

While many Alt-Right representations of medieval culture are historically inaccurate, as The Economist notes, the movement still draws on attitudes and customs present in the Middle Ages which support a white supremacist society.

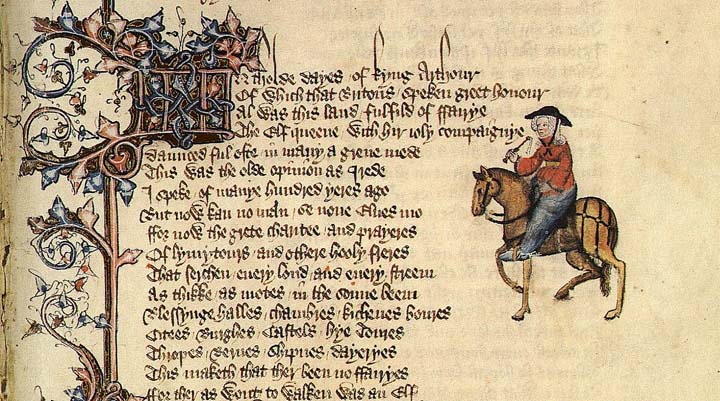

For instance, many alt-right extremists draw on the anti-Semitism present in Medieval European texts and cultures. One such example of this problematic attitude can be found in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in particular, “The Prioress’ Tale.”

This vita, meant to inspire faithful Catholics, in all truth represents Jews as a threat to Christianity. In fact, Chaucer even goes so far as to associate them with the devil. He describes Satan as provoking the Jews to kill the young, saying “Oure first foo, the serpent Sathanas,/That hath in Jues herte his waspes nest,/Up swal, and seide, ‘O Hebrayk peple, allas!/ Is this to yow a thyng that is honest,/That swich a boy shal walken as hym lest/In youre despit, and synge of swich sentence,/Which is agayn youre lawes reverence?’” (Chaucer 559-564).

Not only do these lines portray Satan as swaying the Jews and convincing them to murder the young boy; it also depicts the Jews as inherently evil, as their hearts house Satan’s “waspes nest” (560). Thus, the tale effectively others the Jews, and characterizes them as a villainous people, bent on oppressing the Christians, when in reality, they themselves were often marginalized by surrounding Catholic societies. In fact, in 1290, the Jews were even expelled from England, Chaucer’s home.

The Alt-Right adapts stories such as “The Prioress’ Tale” and others, using them to justify anti-Semitic and white supremacist ideologies. They imagine a homogenous, European medieval society espousing these beliefs, and promote this culture as the ideal society.

How, then, can we combat this abuse of medieval history?

In “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy,”Professor Dorothy Kim says we must begin by unequivocally condemning the alt-right. There is no room for middle ground; she says “Denial is choosing a side. Using the racist dog whistle of ‘we must listen to both sides’ is choosing a side.” Thus, we must begin by simply acknowledging that white supremacy is an issue in the field.

Many are also beginning to tackle this issue by ferreting out the myths surrounding medieval culture. As The Economist explains, “Academics are placing a new emphasis on the ways in which medieval societies differed from the homogeneous world imagined by the alt-right.”

However, this is not enough to fully address the problem at hand. Texts such as “The Prioress’ Tale” demonstrate that medieval societies sometimes did promote harmful ideals, such as anti-Semitism and fear of non-Western cultures. While some might argue that these pieces of literature should be abandoned altogether, this would ignore difficult parts of the past and fail to grapple with them.

Perhaps the best way to teach these texts — and reclaim them from movements such as the Alternative Right — is to begin by giving them context. This context can be developed by bringing in the writings of Jews, women, and people of color into the classroom and discussing the complexities of non-European medieval cultures. People of color, Jews, and women often faced barriers preventing them from participating in European literary traditions. However, expanding the medieval canon to include medieval texts from around the world can help to bring these voices into the classroom and expose students to a wider range of voices.

Furthermore, deconstructing how and why anti-Semitic beliefs developed in Medieval societies — as well as the ways they manifest themselves today — can help unearth the irrational basis of these ideologies. For example, a discussion of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of usury, and Catholics’ reliance on Jews for loans might help a misguided person come to understand the true reasons why anti-Semitism became prevalent in the Middle Ages, and subsequently, reject this prejudice.

Finally, outside of the classroom, it is important to help young people develop healthy communities and identities to inoculate themselves against movements such as the Alt-Right. The movement is known to draw especially on isolated, disaffected young men and offer them not only a means of understanding themselves individually, but also through the lens of a group identity. Thus, it is crucial to help young people develop healthy support networks and form both personal and communal identities around ethical shared values.

These suggestions are only a start to the massive issue of addressing the Alt-Right Movement’s infiltration of the academic sphere and its abuse of history to advance its agenda. Even so, this is a subject that cannot be ignored. To erase the difficult parts of history by attempting to avoid the problem only serves to perpetuate it; it is time to begin discussing ways in which to contextualize medieval history and move forward to create better communities.

Natalie Weber

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited:

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Edited by Robert Boenig and Andrew Taylor, Broadview, 2012.

Hankes, Keegan, and Alex Amend. “The Alt-Right Is Killing People.” Southern Poverty Law Center, Southern Poverty Law Center, 5 Feb. 2018, www.splcenter.org/20180205/alt-right-killing-people.

Kim, Dorothy. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In The Middle, www.inthemedievalmiddle.com/2017/08/teaching-medieval-studies-in-time-of.html.

Southern Poverty Law Center. “Alt-Right.” Southern Poverty Law Center, www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/alt-right.

S.N. “The Far Right’s New Fascination with the Middle Ages.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 2 Jan. 2017, www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2017/01/medieval-memes.

Photo credits:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/134055122@N07/35729897044

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Prioress%27s_Tale