Medieval manuscripts create the conditions for much of our knowledge of the past. The working group on “Jewish and Christian Books in the First Millennium CE” engages Jewish and Christian texts from Late Antiquity to the early modern period, focusing on how material texts and the history of reading enrich our understanding of these texts and their readers. By illuminating the ways in which textual knowledge was—and continues to be—produced, accessed, and preserved, the study of material texts is fundamental to the study of both Judaism and Christianity.

A central emphasis for our working group is the ways that Christian and Jewish communities have oriented themselves around books and reading. For our first meeting of the year, we discussed David Stern’s The Jewish Bible: A Material History(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017). Stern argues that Jewish books have often been adapted in response to the book technologies of neighboring cultures, but are also marked as Jewish through their physical form.

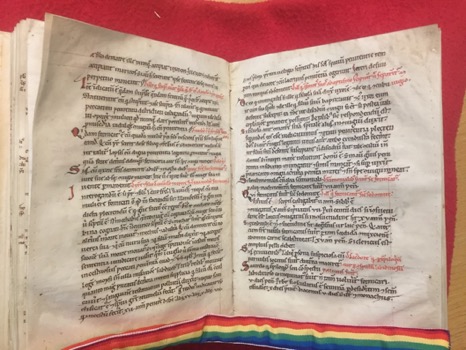

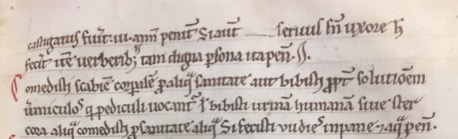

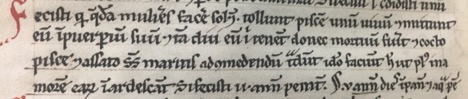

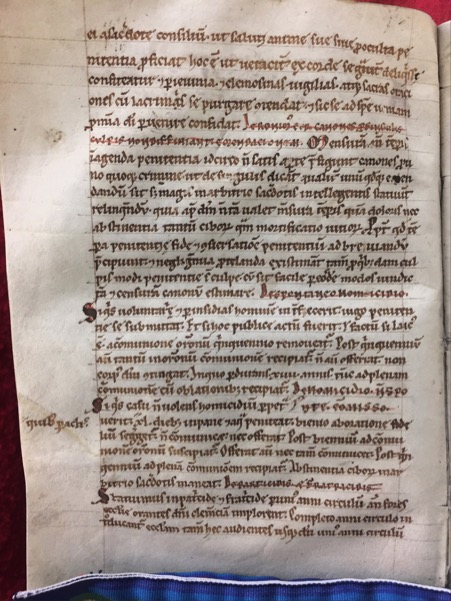

A recurring theme in the working group is how both physical technologies and cultural practices facilitate the creation of textual knowledge. The production of texts builds on complex interaction between spoken language, written text, and habits of reading. In November, Tzvi Novick introduced us to a particular example of this complexity by presenting his work on “Orality, Writing, and Language Choice in Early Roman Palestine.” In our next meeting (1 March), Hildegund Müller will discuss the medieval manuscript transmission of Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos. Her work engages the ways that medieval manuscripts, their scribes, and their readers have preserved and changed Augustine’s oeuvre.

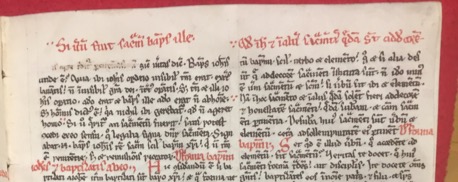

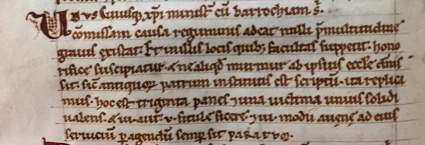

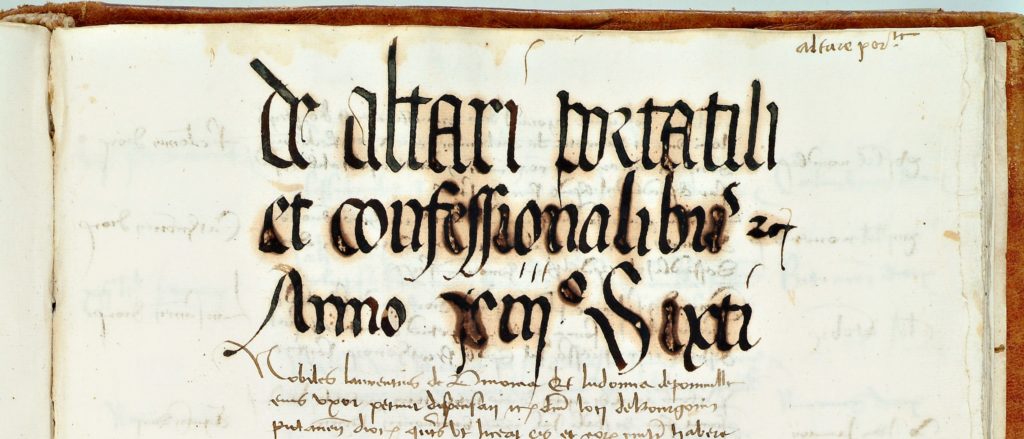

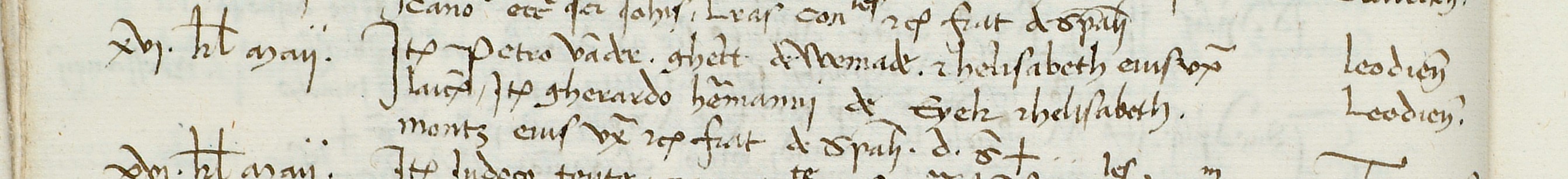

Scribes and readers also curate texts for the benefit of subsequent readers. One way to do this is by providing paratexts, that is, features like tables of contents, section divisions, or explanatory notes that guide the reader and structure the text. In October, Jeremiah Coogan presented his research on the Eusebian apparatus, a set of Gospel cross-references that occurs in late ancient and medieval manuscripts from Ireland to Ethiopia. He argued that the Eusebian apparatus creates new possibilities for reading the Gospels, which we can see at work in a number of examples from Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. On 12 April, Paul Wheatley will present a paper titled “Behind the Veil of Translation: Onomastics, Interpretation, and Revelation.” Paul will discuss onomastic lists, which often appear in biblical manuscripts and explain the names of biblical people and places. Like the Eusebian apparatus, these manuscript features shape how readers encounter sacred text on the page.

Because such paratexts are added by certain readers for the benefit of other readers, they enable us to glimpse medieval reading in action. Another way that we can observe the history of reading is by attending to what readers write. In our February meeting, Andrew King demonstrated how digital analysis can be applied to ancient texts. Andrew’s paper on “The Big Data of Intertextuality and the Book of Deuteronomy” offers an approach to “distance reading” that illuminates trends in the citation of biblical texts by various authors over time.

Modern practices of collection and conservation likewise generate particular bodies of knowledge to be studied. In our January 2019 meeting, the working group looked at Brent Nongbri’s recent monograph, God’s Library: The Archaeology of the Earliest Christian Manuscripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018). Focusing on late ancient manuscripts from Egypt, Nongbri shows how nineteenth- and twentieth-century archeologists, dealers, and collectors shaped the manuscript collections that modern scholars study and what we know about them. Nongbri’s work also engages the physical features of early Christian books and the challenges of historically contextualizing them.

Physical books are always situated in economic, ritual, and readerly contexts. On 31 May, we will host a conference on “The Material Gospel” to discuss the Gospels as material artifacts. Gospel books were powerful objects. Augustine of Hippo complains that his audiences put Gospel books under their pillows to cure toothache. Amulets attest that even short Gospel excerpts were used for protective power. The Gospel in codex format represented Christian identity. Gospel books were processed in liturgy and imposed on the shoulders of ordinands. As an anthological object, the multiple-Gospel codex contributed to the development of a fourfold canonical Gospel. In times of persecution, Gospel books might even be subject to public execution in place of Christ himself. The conference will explore these and similar questions from the first five centuries CE. This conference will serve as a fitting conclusion to this year’s working group, drawing together a wide range of conversations about books and reading.

Jeremiah Coogan, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame