When Eve and Adam ate the forbidden fruit, the Book of Genesis tells us, their eyes were opened, and they knew that they were naked. In modern editions of the Bible, the verses are divided as follows:

6 … and she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave to her husband who did eat.

7 And the eyes of them both were opened, and when they perceived themselves to be naked, they sewed together fig leaves, and made themselves aprons.[1]

The pause comes after the eating of the fruit, emphasizing this act. The immediate results of the act—the opening of the eyes, the recognition of nakedness, and the couple’s decision to cover their nakedness with fig leaves—all follow in quick succession. The next verses detail the further consequences of humanity’s fall. But what if the turning point were not so much the act of choosing to disobey God and eat the fruit, but the cognitive effect of doing so, the revelatory moment when human understanding changed? Such is the interpretation created by one eleventh-century manuscript of the Old Testament in Old English.

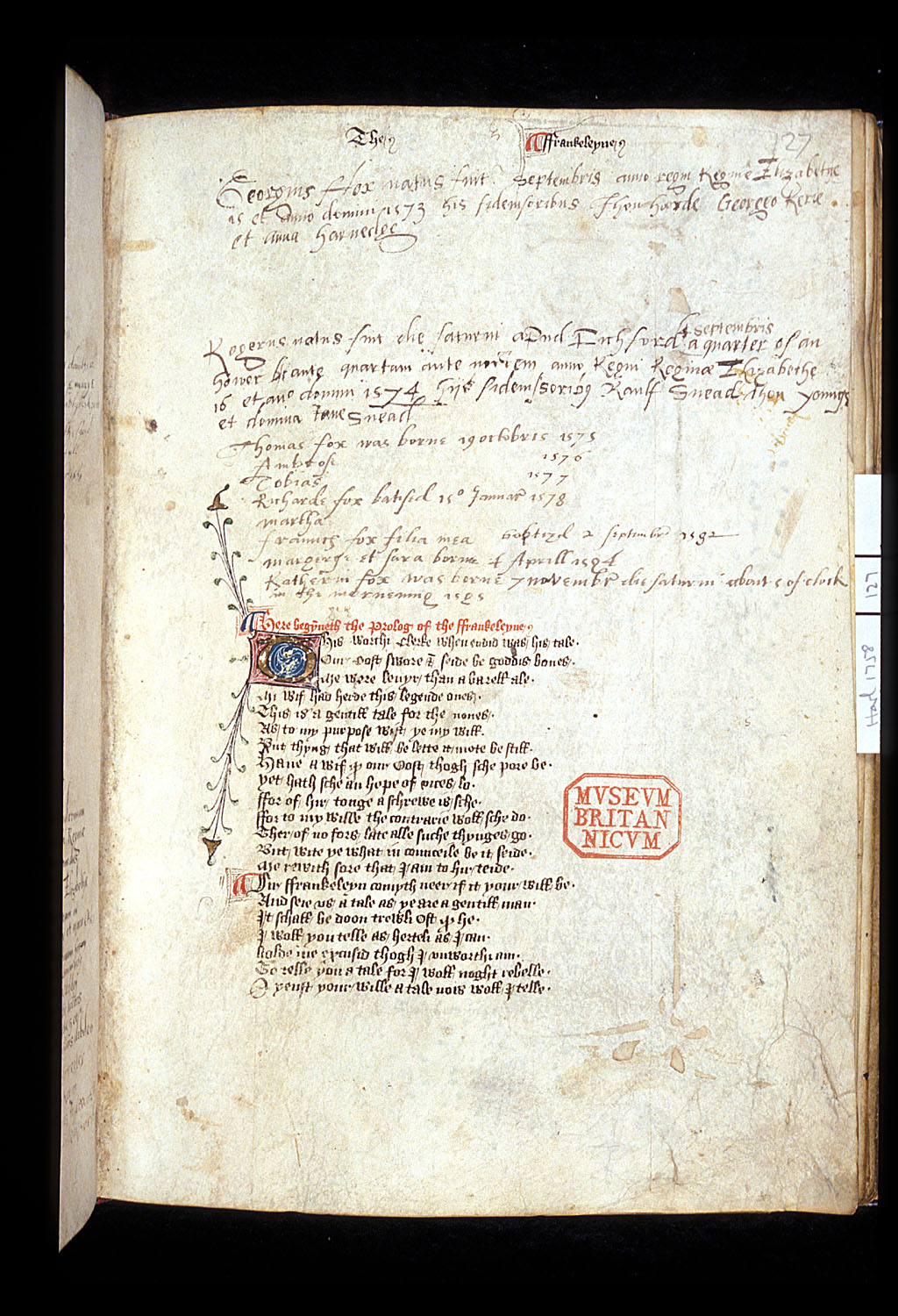

This manuscript (Cambridge, British Library, Cotton MS Claudius B.iv) was probably created around 1020-1040, and is large and heavily illustrated. It contrasts with another surviving manuscript of the Old Testament, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Laud Misc. 509, which was likely based on the same exemplar, but which is small and unillustrated. The punctuation differs significantly throughout the two manuscripts. Laud Misc. 509 punctuates Genesis 3:6-7 as follows (the ⁊ symbol is the scribal abbreviation for “and”):

⁊ genam þa of þæs treowes wæstme. ⁊ geæt ⁊ sealde hire were. He æt þa ⁊ heora begra eagan wurdon geopenode hig oncneowon þa þæt hig nacode wæron ⁊ siwodon fic leaf ⁊ worhton him wædbrec.

[and took then of the tree’s fruit. and ate and gave (it) to her husband. He ate then and the eyes of them both were opened they knew then that they were naked and sewed fig leaves and made themselves clothing]

The passage is a bit of a run-on. Punctuation separates Eve’s act of taking the fruit from her eating it and giving it to her husband, but everything that follows does so without a pause.

Contrast this with the same passage in MS Claudius B.iv:

⁊ genam ða of ðæs treowes wæstme. ⁊ geæt. ⁊ sealde hyre were. He æt ða ⁊ heora begra eagan wurdon geopenode .·.

[and took then of the tree’s fruit. and ate. and gave (it) to her husband. He ate then. and the eyes of them both were opened .·.]

The punctuation mark .·. is the “strongest” punctuation mark in the scribe’s repertoire. Used infrequently compared to the single punctus, it represents the biggest pause. And that is the last line on the page (although there is in fact space for at least a couple more words). The reader must pause here at the moment when the eyes of the first human beings are opened, and lift their own eyes to the top of the next page. This page begins with an image: the naked Eve and Adam, Adam in the act of eating the fruit, the serpent in a tree to the left. The text resumes below it, midway through Genesis 3:7, with a large colored initial that, combined with the previous punctuation and page change, suggests that this should be considered a significant break in the text, and that something new is beginning:

Hi oncneowon ða ðæt hi nacode wæron. ⁊ sywodon him fic leaf. ⁊ worhton him wædbrec.

[They knew then that they were naked. and sewed themselves fig leaves. and made themselves clothing.]

While the image still suggests the significance of the eating of the fruit, the page layout and strong punctuation invite the reader to pause and reflect at a different point in the narrative: the time when “the eyes of them both were opened” and the knowledge of good and evil was revealed. What did the world look like, in that moment?

Cambridge, British Library, Cotton MS Claudius B.iv, fols. 6 verso and 7 recto. (A twelfth-century annotator has added commentary in Latin at the bottom of the pages and within the borders of the second image.)

Emily Mahan

PhD Student, Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

Further reading:

Rebecca Barnhouse and Benjamin C. Withers, The Old English Hexateuch: Aspects and Approaches, Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000.

N. Doane and William P. Stoneman, Purloined Letters: The Twelfth-Century Reception of the Anglo-Saxon Illustrated Hexateuch (British Library, Cotton Claudius B. iv), Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2011.

Benjamin C. Withers, The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch, Cotton Claudius B.iv: The Frontier of Seeing and Reading in Anglo-Saxon England, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.