Titular Confusion in the Economic Records of Late Medieval Burgundy

Queen Elizabeth II. The Earl of Grantham. The King in the North. Rank and titles from popular television shows like The Crown, Downton Abbey, and Game of Thrones capture the modern imagination with images of conniving courts, opulent balls, and fancy dinners. But what did rank and title signify to the medieval mind? This question has provided the backdrop for some of the most prominent works of medieval scholarship, and the question has continued to interest and influence current work. One medieval society, in particular, had a healthy respect for, and perhaps an unhealthy obsession with, titles and status: late medieval Burgundy, the Grand Duchy of the West.

Burgundy earned its name of “Grand Duchy,” by the power of its statecraft and economy. At any given point, the Duke had a massive entourage of counselors. For major affairs of state, such as making peace with France, the numbers could go into the hundreds of men (Russell, Congress of Arras). The Duke kept very careful economic records of his payments to his subordinates at court, in what is called the Recette Générale. In studying the Recette, one is immediately struck by the length and structure of the titles of each person receiving payment. Titles mattered to the people of Burgundy. The order in which their titles were listed mattered too:

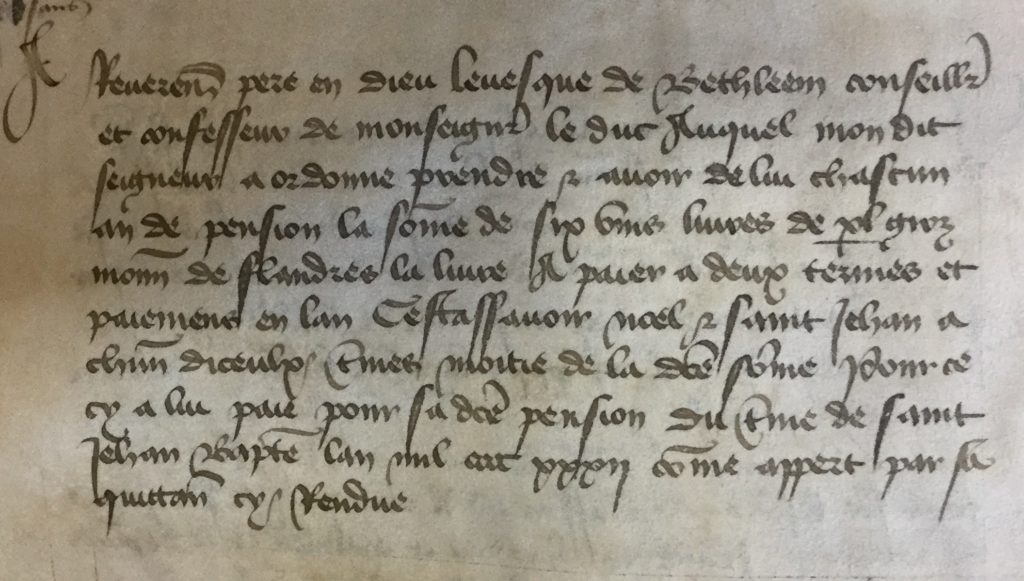

The picture above is a standard entry in the Recette Générale. It reads (translated from middle French) “to the Reverend father in God, the bishop of Bethlehem, counselor and confessor to monseigneur the duke.” The order of the confessor’s titles here is consistent with the economic records in Lille: first came the appellation, here “reverend father in God,” but it could also be something like “sir,” or “my lord.” Following next generally was the name of the individual, which is omitted in this instance. Luckily we do know the name of this confessor was Friar Laurens Pignon from payments in earlier records. After the name came the confirmation of any title held by the payee and the place it was held. Here it is “the bishop of Bethlehem.” Lastly, the record includes the position (if any) the person in the entry held at court: “counselor and confessor of monseigneur the duke.”

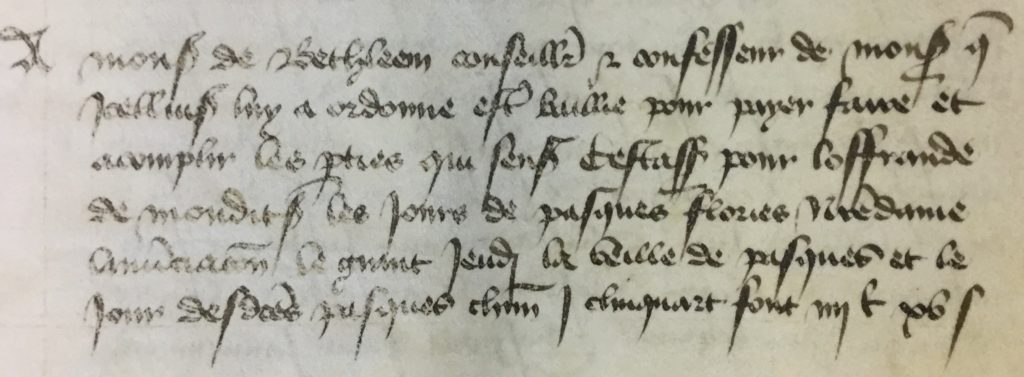

With such careful attention placed on the titles, it is especially interesting when the accounts strayed from their standard formula. One mild variation is the exclusion of the episcopal title in payment to the confessor Pignon from two years earlier:

As one can see, the expected “reverend father in God, the bishop” is missing. The receiver general has replaced the longer title with an abbreviated “monseigneur of Bethlehem.” Such a title does not indicate his episcopal role, although the normal positions at court are included, “counselor and confessor.” The omission of the first half of the bishop’s title is not especially surprising here. The confessor had appeared multiple times earlier in the accounts with his full title included (f. 27v-29r). In all likelihood, the explanation here is an instance of rushed record keeping. There was only one monsieur of Bethlehem, after all.

A more interesting “error” in the accounts concerning the confessor occurs in only one year of the Burgundian accounts: 1432, the same year that Pignon transferred from his old diocese of Bethlehem to the more prestigious diocese of Auxerre.

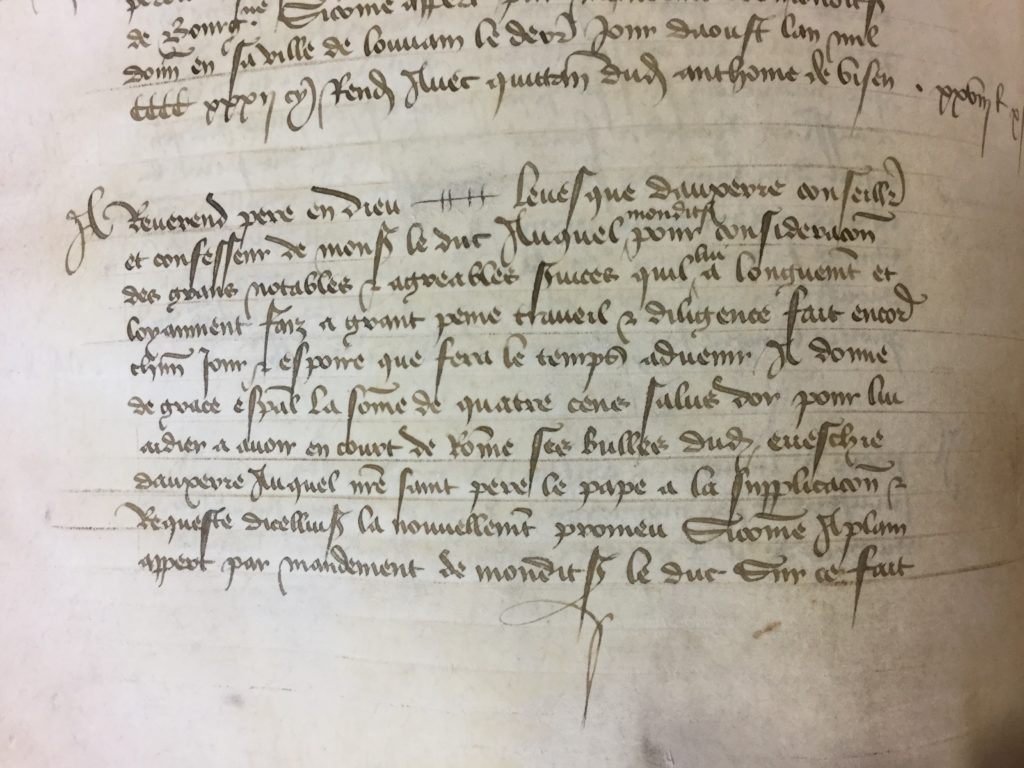

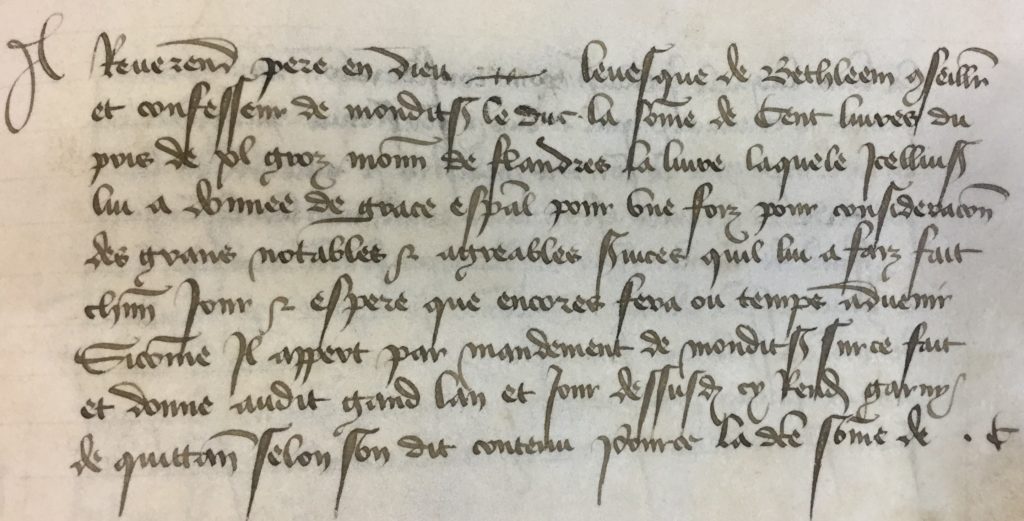

Here, the title proceeds according to the expected formula: “to the Reverend father in god, the bishop of Auxerre, counselor and confessor of monseigneur the duke.” According to the careful naming conventions of the Recette Générale, the title of Auxerre should be found throughout the rest of the year. In fact, the opposite is true. The title of Auxerre appears one additional time in the accounts of 1432. However, the Duke of Burgundy pays Pignon ten more times in the year, always with the title of “Reverend father in god, the bishop of BETHLEHEM, counselor and confessor of monseigneur the duke.”

The reversion by the Recette Générale to Pignon’s old title is undoubtedly an aberration- in the following years until his death in 1449, Pignon is identified as the Bishop of Auxerre. More importantly, the title of Bishop of Bethlehem no longer correctly referred to him- A fellow Dominican by the name of Dominic filled the post in 1433 (Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica vol. 2, 118).

There are a number of explanations for the oversight. The easiest one to dismiss would be the intentional disrespect of Friar Pignon by the Recette Générale by referring to him in a less prestigious way. No surviving evidence suggests that Pignon ever had issues with the Duke’s accountants. Indeed, he even helped them perform their duties in rare instances. Another explanation is that the members of the Recette Générale did not know of Pignon’s promotion- there were many members of the accounting body, sometimes with multiple receiver generals in a year. Perhaps the lower levels of the administration simply did not know of Pignon’s advancement to a higher bishopric. A third possibility is that the Recette Générale knew Pignon too well- again, Pignon shows up in the economic records every year he was in the Duke’s service, from 1412-1449. In 1432, he had been at court for 20 years and had been the Bishop of Bethlehem for almost a decade. To my mind, this is the most sensible and likely explanation.

This example of Laurens Pignon is meant to show something simple about the use of titles in the medieval period. Even a culture highly cognizant of standing, title, and rank made mistakes in this regard. The members of the Recette Générale knew Laurens Pignon, and had known him for many years. To them, he was the Bishop of Bethlehem, the counselor and confessor to the Duke. The promotion to Auxerre undoubtedly felt real to the confessor, but to the rest of court, it perhaps took more time to register.

Further Reading-

Blockmans, Wim, Antheun Janse (eds.). Showing Status: Representation of Social Positions in the Late Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols, 1999.

Duby, Georges. The Three Orders: Feudal Society Reimagined. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Eubel, Konrad. Hierarchia Catholica medii aevi vol. 2. Regensburg: Monasterii Sumptibus et typis librariae Regensbergianae, 1913.

Russell, Joycelyne Gledhill. The Congress of Arras, 1435: A Study in Medieval Diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955.

http://www.archivesdepartementales.lenord.fr