Margery Kempe, the protagonist of the Book of Margery Kempe, did not like to talk about her visions, as my previous blog discusses.

The Book is not shy about her reasons. Acting but not telling her audiences in church or on pilgrimage creates the persecution on behalf of Christ she so desires. She explains her innermost visions to high clergy in order to seek their confirmation that her revelations do come from God.

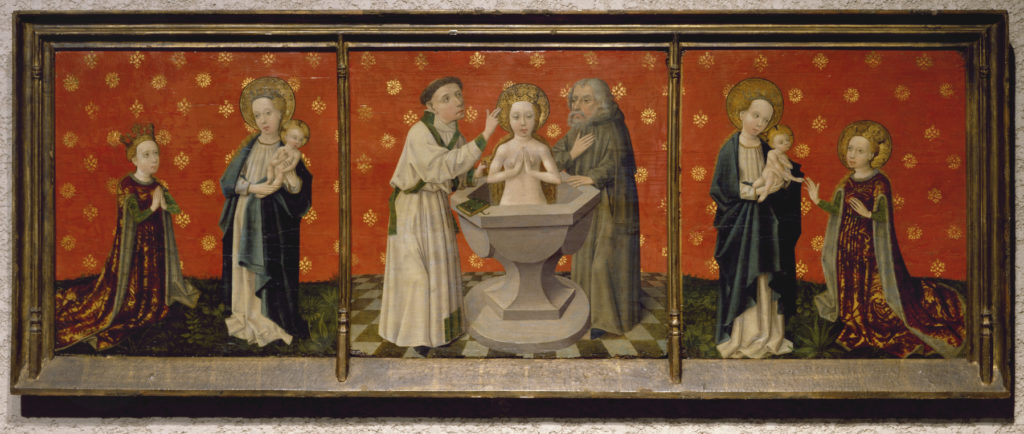

Recent research has added demonstrated an additional theological dimension. Kempe’s externalization of her special piety and concealment of her true gifts are a saintly imitatio (or hagiographical tropes), but not of contemporary saints she admires like Birgitta of Sweden. Instead, she crafts a life following the romance template of the early Church virgin martyrs, whose legends were wildly popular in the fifteenth century. [1] These saints have intimate encounters with Christ that remain their secret, but display their Christian heroism by enduring persecution and death for their faith.

Some scholars have argued that the result is a unique theology of time. Kempe essentially lives the legendary past in the present, collapsing chronological eras into a single sacred time. However, her fifteenth-century contemporaries fail to recognize her imitatio and scorn her for her behaviors. Thus, the distance between the era of the virgin martyrs and fifteenth-century England also causes the (very partial) ostracization that allows Kempe to recapitulate St. Katherine and St. Cecilia. She inhabits a collapsed past-present that demonstrates and criticizes the “historical specificity” of both women’s holiness and religious authority. [2]

Despite her imitatio of saints who kept their secrets, however, Kempe did indeed talk about her visions. She shared her “high contemplations” with a series of priests, bishops, and men who would become her confessor—in many cases, people she barely knew and would never see again. The Book also portrays her describing her visions to her scribes, one of whom was her son. Nor are her disclosures merely a matter of compliance with discretio spirituum, that is, the need to seek authentication of the divine origin of visions from a Church authority. Concealing her visions from the general public, Kempe has little need to seek legitimization for her own safety or public sanctity. From a hagiographical perspective, too, the succession of Church officials unfamiliar with her instead of a longtime confessor is more reminiscent of Marguerite Porete’s failed attempt to insulate herself from heresy charges than of late medieval holy women.

Kempe’s concealing and revealing of her visions are a case study for common patterns of self-disclosure. [3] People make decisions about divulging personal information by balancing the reward (human connection) with risk (loss of control over public identity). Thus, we share our most private information with the people closest to us, with whom we seek ever-closer ties and whom we trust the most not to misunderstand or repeat the information. We also share more personal details with people we barely know, because we have to build a relationship from the ground up, and there is little chance of a repeated interaction being affected.

Thus, her imitatio—her sanctity—anchors Kempe-the-protagonist even more fully in the social web of the present, rather than making her a “woman out of time.” Equally or perhaps more importantly, it allows Kempe-the-author to anchor the Book more firmly in the demands of fifteenth-century devotion.

Kempe’s repeated disclosure of her visions to numerous clergy does not simply authenticate her visions. Rather, it draws the reader’s attention to their presence in Kempe’s life and in the Book again and again. Like its protagonist’s desire to live the past in the present, the lavish descriptions of her visions and the repeated references to them allow the Book to have it both ways, as it were. On one hand, it can tell the story of its non-virgin, unmartyred virgin martyr: a (semi) pariah in the world, who is sustained by her hidden intimacy with Christ. On the other, the visions and dialogues mirror the format of much fifteenth-century devotional and didactic literature. The visionary discourse highlights the Book as a text that teaches its audience rather than defending its subject.

In this light, the “stereotypical” nature of Kempe’s visions and the apparent failure of the Book as hagiography can be seen as both purposeful and successful. Kempe’s externalized piety is, frankly, more interesting to most modern readers than yet another mystical marriage. [4] Thus, we are also more interested in the Book’s goals with respect to Kempe herself: justification of her earlier actions, perhaps, or a full-blown hagiography aimed at jump-starting a public cult after her death. [5]

The bibliographic evidence tells a different story for medieval readers. Kempe the author earned the unusual distinction among women mystical writers of having her work published in the early decades of print. Printer Wynkyn de Worde’s “A shorte treatyse of contemplacyon…taken out of the boke of margerie kempe of lynn” trims down the Book almost exclusively to Christ’s monologues to Kempe. [6] This can be seen as a failure of Kempe the protagonist to establish herself as a person and as a saint, to the extent of emphasizing what she tried to conceal. [7]

It is that effort to conceal, however, that allows the Book to do the opposite: draw Kempe’s visions into the foreground. It isn’t ironic that Margery Kempe and her Book became famous at the end of the Middle Ages for her hidden visions rather than the life she lived. Instead, it is exactly what Kempe the protagonist and Kempe the author wanted.

—

[1] Sarah Salih, Versions of Virginity in Late Medieval England (Brewer, 2001), 166-169.

[2] Catherine Sanok, Her Life Historical: Exemplarity and Female Saints’ Lives in Late Medieval England (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 122-26.

[3] See, for example, W. B. Pearce and S. M. Sharp, “Self-Disclosing Communication,” Journal of Communication 23: 409-25.

[4] Karma Lochrie, Vickie Larsen, and Mary-Katherine Curnow, for example, have even argued for the comedic possibilities of Kempe the protagonist and of the Book itself: Lochrie, Margery Kempe and Translations of the Flesh (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991); Larsen and Curnow, “Hagiographic Ambition, Fabliau Humor, and Creature Comforts in The Book of Margery Kempe,” Exemplaria 25, no. 4 (2013): 284-302.

[5] Katherine J. Lewis, “Margery Kempe and Saint Making in Later Medieval England,” in A Companion to The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Lewis and John H. Arnold (D.S. Brewer, 2004), 195-215.

[6] The text of Shorte Treatyse can be found in The Book of Margery Kempe: The Text from the Unique MS Owned by Colonel W. Butler-Bowdon, Vol. 1, ed. Sanford Brown Meech with Hope Emily Allen (Oxford University Press, 1940), 353-57.

[7] See, for example, Lewis, 215; Anthony Goodman, “Margery Kempe,” in Medieval Holy Women in the Christian Tradition, c.1100-c.1500, ed. Alastair Minnis and Rosalynn Voaden (Brepols, 2010), 226.

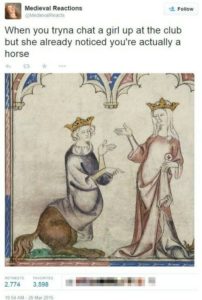

We’ve all seen the “I take 1000 selfies for every one I can post” Instagram admissions, and the smartphone videos where the gorgeous YouTube star turns this way and that to display how she can go from (ridiculously thin and good-looking) normal to supermodel quality with angles and makeup. These social media accounts have a rhetoric of their own. The “Feet in the foreground, beautiful scenery in the background” photo means ultimate relaxation. Twitter has its own grammar, often departing from “proper” English, that mashes up different vernaculars and changes from meme to meme.

We’ve all seen the “I take 1000 selfies for every one I can post” Instagram admissions, and the smartphone videos where the gorgeous YouTube star turns this way and that to display how she can go from (ridiculously thin and good-looking) normal to supermodel quality with angles and makeup. These social media accounts have a rhetoric of their own. The “Feet in the foreground, beautiful scenery in the background” photo means ultimate relaxation. Twitter has its own grammar, often departing from “proper” English, that mashes up different vernaculars and changes from meme to meme.