Grendel’s mother has long been regarded by scholars as the least monstrous of the three—not being an obvious vampire-cannibal like Grendel nor a fire-breathing dragon. Her vengeful response to the death of her son, and her decision to continue the feud between the Grendelkin has been regarded as ethical (within the broader context of warrior ethos), legal (within the context of early medieval Norse and English laws), and even heroic (aligned with the heroism as depicted in the poem).

While I would generally agree with this broad characterization of Grendel’s mother, and there is no doubt that her actions mirror those of any avenging warrior in Beowulf, to erase her monstrosity seems to ignore at least some of the evidence. While I do not find her maternity at all indicative of abject horror (indeed quite the opposite as it is her identity as “mother” that humanizes her in my view), certain terms used to describe her and indeed everything from her association as Caines cynn “Cain’s kin” (107; 1261-65) and the hellish descriptions of her lair suggest some measure of monstrosity embedded in her character. And for this Halloween, we will spend some time unpacking the nature of her monstrosity.

I would contend that the main reason scholars argue about Grendel’s mother’s monstrosity and characterization is because of her enigmatic design. As I point out in my dissertation, riddles encode Beowulf, and, in my opinion, employ riddling rhetorical strategies, especially imitation, equivocation, esotericism and paradox. These obfuscations help account for the many irregularities observed in the poem the scholars have scratched their heads over for more than a century and help explain why often the heroes looks like the monsters—and the monsters like the heroes.

Because of the influence of riddling rhetorical strategies on Beowulf, turning to the Anglo-Latin enigmata tradition is an especially fruitful practice, especially in explorations of monstrosity in the poem. Indeed, monsterized riddles have long been a feature starting with the late classical enigmatist, Symphosius, who establishes the Anglo-Latin tradition, includes numerous riddles on wondrous creatures, such as the phoenix (Enigma 31). Similarly, Aldhelm’s enigmata also feature numerous monsterized riddles, in some cases the solution is a wondrous creature (as with Symphosius’ paradoxical phoenix-riddle), in other cases the mundane is made monstrous through imitation, and the monsterization is another mechanism of obfuscation (as in Aldhelm’s Enigma 97 solved nox). Even Boniface, whose riddles center on vices and virtues, monsterizes his vice-riddles in the mode of Prudentius’ Psychomachia, a popular classroom text in early medieval English which depicts vices as monsters in an allegorical epic.

But what does this have to do with Grendel’s monstrous mother? Let’s start with her introduction and the complex portrait it paints:

Þæt gesyne wearþ,

widcuþ werum, þætte wrecend þa gyt

lifde æfter laþum, lange þrage,

æfter guðceare: Grendles modor.

Ides aglæcwif yrmþe gemunde,

se þe wæteregesan wunian scolde,

cealde streamas, siþðan Cain wearð

to ecgbanan angan breþer,

fæderenmæge. He þa fag gewat,

morþre gemearcod, mandream fleon,

westen warode.

“That became manifest, widely known to men, that an avenger still lived after the hostile one, for a long time, after war-grief: Grendel’s mother. A lady, a fearsome woman remembered misery, he who must inhabit the terrible-waters, the cold streams because Cain became the edge-slayer to his only brother, kin of the same father. He then went hostile, marked by murder, fled the joys of men, inhabiting the wilderness.”

Beowulf, 1255-65.

The first term used to describe Grendel’s mother emphasizes her desire for vengeance. The narrator names her a wrecend “avenger” (1256) —an appropriate title considering her entire characterization is framed by revenge and feuding—and her motive is thrice repeated almost verbatim and with language that could apply equally to avenging heroes in the poem (1276-78, 1339-1340, 1546). Moreover, Grendel’s mother’s is thrice described as wif “woman” (1259, 1519, 2120,) and even twice as an ides “lady” (1259, 1351) establishing gender as one of the pillars of her characterization, alongside her roles as avenger and mother. Kinship ties are further emphasized when Grendel’s mother is described as Grendles maga “Grendel’s female relative” (1391) and twice as Grendles mæg “Grendel’s kinsman” (2006, 2353), which account for her desire for revenge in upholding the warrior ethics and continuing the feud between the Danes and the Grendelkin.

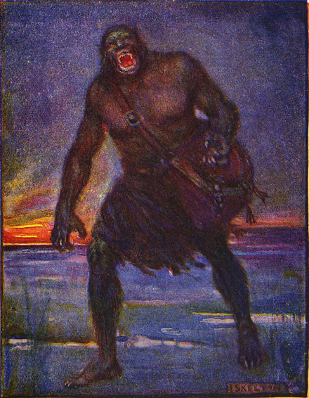

Moreover, like the monstrous vices in Prudentius’ Psychomachia and Boniface’s Enigmata, the avenger—Grendel’s mother—is clearly wondrous and monstrous in certain descriptions of her. She and her lake monsters are wæteregesa “water-terrors” (1260). Grendel’s mother is called se broga “the terror” (1260), and together with her son, she is described as mihitig manscaða “man-slayer” (1339), micle mearcstapa “great marked-wanderer” (1348), dyrna gast “secret spirit” (1357), ælwiht “alien thing” (1518), thrice as ellorgæst “foreign spirit” (1349, 1617, 1621) and even deofol “devil” (1680). She is even described as a merewif mihtig “mighty mermaid” (1519), aglæcwif “fearsome warrior woman” (1259) or wif unhyre “untamed woman” (2120), grundwyrgenne “ground wolf” (1518) and twice is characterized with the compound a brimwulf “sea-wolf” (1506, 1599).

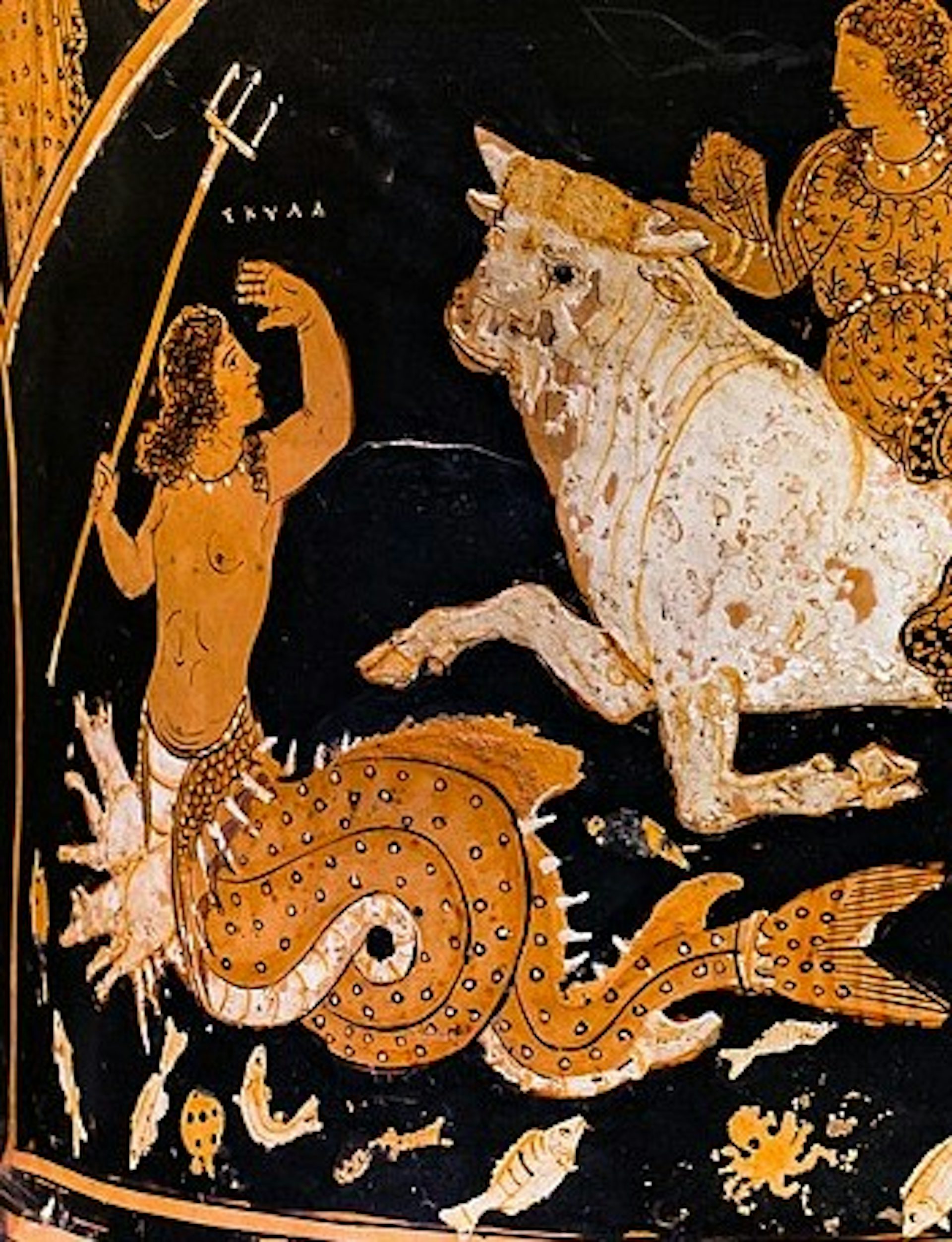

It is my contention that descriptions of Scylla—a classical monster, famously featured in the Odyssey and popular in Anglo-Latin literature contemporary with Beowulf—likely influence the characterization of Grendel’s mother, a riddle embedded in the poetic compounds used to describe her and in the depiction of her monstrous lair.

Scylla is a monstrous sea creature from Greek mythology, known for inhabiting a narrow strait opposite the whirlpool Charybdis. She often has multiple heads with each head bearing a set of sharp, ravenous teeth. Scylla’s body is a woman’s often combining serpentine, aquatic and canine features. She emerges from a rocky cliffside and narrow passage where she lives. She preys on passing sailors, snatching them from ships with her many heads and her “sea dogs” which accompany her. Once a beautiful nymph, she becomes cursed and exiled.

Scylla is the riddle-subject of Aldhelm’s Enigma 95 (solved Scilla) and is featured in his prose De uirginitate (X). Aldhelm’s Enigma 95 describes Scylla as follows:

Ecce, molosorum nomen mihi fata dederunt

(Argolicae gentis sic promit lingua loquelis),

Ex quo me dirae fallebant carmina Circae,

Quae fontis liquidi maculabat flumina uerbis;

Femora cum cruribus, suras cum poplite bino

Abstulit immiscens crudelis uerba uirago.

Pignora nunc pauidi refereunt ululantia nautae,

Tonsis dum trudunt classes et caerula findunt.

Uastos uerrentes fluctus grassante procella,

Palmula qua remis succurrit panda per undas,

Auscultare procul quae latrant inguina circum.

Sic me pellexit dudum Titania proles,

Ut merito vivam salsis in fluctibus exul.

“Look, the Fates gave me the name of dogs—thus does the language of the Greeks render it in words—ever since the incantations of dread Circe, who stained the waters of the flowing mountains with her words, deceived me. Weaving words, the cruel witch deprived me of thighs together with shins, and calves, together with knees. Terrified mariners relate that, as they impel their ships with oars and cleave the sea, sweeping along the mighty wave while the tempest rages, where the broad blade of howling offspring that bark about my loins. Thus the daughter Titan [scil. Circe] once tricked me, so that I should live as an exile—deservedly—in the salty waves.”

Lapidge and Rossier, Aldhelm: The Poetic Works, 91.

In this riddle, solved Scylla (Scilla), Aldhelm emphasizes her canine connection, and gives a reference to her origin in Greek mythology and her transformation at the hands of the witch, Circe. There is also mention of the danger she poses to any who sail by her watery abode, alongside her “howling offspring that bark” about her an further threaten wayward travelers.

Scylla also appears twice in the Liber monstrorum (I.14, II.19), where she is described in detail. This first mention from Liber monstrorum I.14 in the section on humaniod monsters is as follows:

Scylla monstrum nautis inimicissimum in eo freto quod Italiam et Siciliam interluit fuisse perhibetur capite quidem et pectore uirginali sicut sirenae, sed luporum uterum et caudas delfinorum habuit. Et hoc sirenarum et Scyllae distinguit naturam quod ipsae morifero carmine mauigantes decipiunt et illa per uim fortitudinis marinis succinta canibus miserorum fertur lacerasse naufragia.

“It is reckoned that Scylla has been the monster most hostile to sailors in that channel which washes between Italy and Sicily, having indeed the head and chest of a maiden (like the sirens), but the belly of a wolf and the tail of dolphins. And what distinguishes the nature of the sirens from Scylla is that they deceive seamen by their deadly song, whilst she with the strength of her force, girt about with sea-dogs, is said to have mangled the wrecks of the unfortunate .”

Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 266-67.

This description emphasizes her superlative hostility [inimicissimum]—similar to Grendel’s mother’s characterization as an aglæcwif “fearsome warrior woman” (1259) or wif unhyre “untamed woman” (2120). Emphasis on the narrow channel where Scylla resides shifts to her hybrid representation with “the head and chest of a maiden (like sirens) but the belly of a wolf and the tail of a dolphins” (fuisse perhibetur capite quidem et pectore uirginali sicut sirenae, sed luporum uterum et caudas delfinorum habuit). This establishes Scylla as a woman-canine-marine creature, combining “maiden” (virgo), “wolf” (lupus), and “dolphin” (delphinus) parts. Moreover, she is twice compared to the treacherous sirens, while explaining that unlike the sirens, who use song to ensnare their victims, Scylla uses force, violence and her mighty strength, with her “sea-dogs” (marinis canibus) to take down unfortunate sailors who enter her domain.

In the second section, centered on bestial monsters, there is an entry on the sea-beasts of Scylla. Liber monstrorum II.19 reads as follows:

fingunt quoque poetae inmari Tyrrheno ceruleos esse canes, qui posteriorem corporis partem cum piscibus habent commune. Ipsis quoque Scyllam ratem Ulixis lacerans marinis succincta canibus describitur.

“the poets also image that there are azure dogs in the Mediterranean, the hind parts of whose bodies they share with fish; also girt round with these same sea-dogs Scylla is described tearing apart the ship of Ulysses”

Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 266-67.

This entry focuses on the “azure dog” (ceruleos canes) or “sea dogs” (marinis canibus) of Scylla, which are described as featuring canine heads and legs, but “the hind parts of whose bodies they share with fish” (qui posteriorem corporis partem cum piscibus habent commune) making them a canine-marine hybrid creature. Scylla is directly mentioned in connection with her accompanying sea-monsters, and the passage directly references the struggles of Odysseus [i.e. Ulysses] when he encounters Scylla on his epic journey home.

The key features of Scylla’s narrow channel are present also in the monster-mere found in Beowulf which is the home and hall of the Grendelkin. Grendel’s Mother’s lair is described in the poem as follows:

Hie dygel lond

warigeað, wulfhleoþu, windige næssas,

frecne fengelad, ðær fyrgenstream

under næssa genipu niþer gewiteð,

flod under foldan.

“They [Grendelkin] inhabit the secret land, the wolf-slopes, the windy narrows, the dangerous fen-path, where the mountain stream cascades downward under the cover of cliffs, the flood under the land.”

Beowulf, 1357-61.

This description emphasizes the dangerous narrows and the crafty cliffs surrounding the monstrous abode and in this way echoes Scylla’s watery domain. In this passage are numerous references to the steep and narrow geography, especially in descriptions of the wulfhleoþu windige næssas “wolf-slopes (and) windy narrows” (1358), and fyrgenstream under næssa genipu, “a mountain river under the cover of cliffs” (1359-60). As Beowulf enters the waves, he finds himself, like those caught by Scylla in the Odyssey, in a violent struggle for his life at the hands of a ferocious woman who pulls him to the depths of her haunted lake. The narrator explains how:

Bær þa seo brimwylf, þa heo to botme com,

hringa þengel to hofe sinum,

swa he ne mihte, no he þæs modig wæs,

wæpna gewealdan, ac hine wundra þæs fela

swencte on sunde, sædeor monig

hildetuxum heresyrcan bræc,

ehton aglæcan. ða se eorl ongeat

þæt he in niðsele nathwylcum wæs,

þær him nænig wæter wihte ne sceþede,

ne him for hrofsele hrinan ne mehte

færgripe flodes; fyrleoht geseah,

blacne leoman, beorhte scinan.

Ongeat þa se goda grundwyrgenne,

merewif mihtig .

“When she came to the bottom, the sea-wolf bore the prince of rings to her hall, so he could not, no matter how brave he was, wield weapons, but so many wonders afflicted him while swimming, many a sea-beast poked the battle-armor with battle-tusks, harassed the fearsome assailant (Beowulf). Then the man perceived that he was in some kind of hostile-hall, where no water could harm them at all, nor could the sudden grasps of the flood touch them because of the roofed-hall. He saw firelight, pale illumination brightly shining. Then the good one (Beowulf) perceived the bottom-wolf, the mighty sea-woman.”

Beowulf, 1506-1519.

In reading this passage from the poem, we can observe numerous parallels between Grendel’s mother and Scylla, which I believe suggests that the classical monster, frequently featured in Anglo-Latin texts, may have influenced the depiction and characterization of Grendl’s mother. Just like with Scylla’s channel, the monster-mere in Beowulf includes sea-creatures that attack anyone who enters their watery lair. Both Scylla and Grendel’s mother are ancient, cursed and exiled monsters, the former as a result of a witch’s curse, the latter is prediluvian, cursed and marked as kin of Cain. Grendel’s mother seems to travel with sea-beasts (nicoras) which resemble Scylla’s sea-dogs. Both Scylla and Grendel’s mother are hybrid women monsters—featuring both canine or lupine characteristics (as indicated by her description as brimwulf “sea-wolf” and grundwyrgenne “bottom-wolf”) characteristics and piscine or serpentine characteristics (as indicated by her description as merewif “mermaid”). And, both Scylla and Grendel’s mom occupy a craggy narrow passage that is terrifying and dangerous for sailors or sea-men.

While I would not push so far as to contend that Grendel’s mother is intended as a literal representation of Scylla, and while I agree with others who have observed her ethically complex characterization, it seems plausible—even probable—that the famous Scylla could have influenced her enigmatic monsterization. At the very least, many counted among the learned audiences of Beowulf in early medieval England would likely have discerned the numerous and noteworthy parallels between these two monstrous women.

Richard Fahey, PhD

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Damme

Selected Bibliography

Acker, Paul. “Horror and the Maternal in Beowulf.” Publication of the Modern Language Association 121.3 (2006): 702-16.

Aldhelm. Aldhelm: The Poetic Works. Translated by Michael Lapidge and James L. Rosier. Dover, NH: D. S. Brewer, 1985.

—. Aldhelm: The Prose Works. Translated by Michael Lapidge and Michael Herren. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 1979.

Fahey, Richard. “Enigmatic Design and Psychomachic Monstrosity in Beowulf.” Dissertation: University of Notre Dame, 2020.

Hennequin, M. Wendy. “We’ve Created a Monster: The Strange Case of Grendel’s Mother.” English Studies 89.5 (2008): 503-23.

Klaeber’s Beowulf, 4th Edition. Edited by Robert D. Fulk, Robert E. Bjork and John D. Niles. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, [reprint] 2009.

Kiernan, Kevin S. “Grendel’s Heroic Mother.” In Geardagum 6 (1984): 13-33.

Lockett, Leslie. “The Role of Grendel’s Arm in Feud, Law, and the Narrative Strategy of Beowulf.” In Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge (I), edited by Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe and Andy Orchard, 368-88. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Orchard, Andy. A Critical Companion to Beowulf. Cambridge, UK: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

—. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Sayers, William. “Grendel’s Mother, Icelandic Gryla, and Irish Nechta Scene: Eviscerating Fear.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 16 (1996): 256-68.