Trolls have a deep and murky literary history. Trolls haunt protagonists in Old Norse-Icelandic sagas. Trolls snatch gruff billygoats crossing bridges in grim fairy tales. In modern novels, trolls capture (and intend to eat) wandering dwarves and hobbits, and trolls sulk about in wizard’s dungeons, leaving a terrible stench wherever they go. Let us not forget, of course, trolls are also fluorescent-haired dolls with gems for bellybuttons.

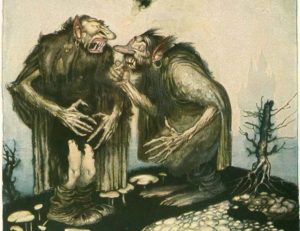

Acknowledging exceptions like the popular dolls (which were recently adapted into DreamWorks Animation movies and a television series), trolls in the modern imagination are generally represented as resembling a giant, but less human and more monstrous. Trolls are often racialized, depicted as pale, grey or green-skinned and regarded as ugly, with dim intelligence and a tendency towards evil.

This stereotypical representation of trolls features in cult classic films such as Troll directed by John Carl Buechler (1986), Troll 2 directed by Claudio Fragasso and originally called Goblins (1990), and more recently Trollhunter (Trolljegeren) directed by André Øvredal (2010).

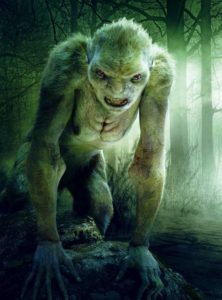

These modern representations of trolls are based on medieval literary models, especially swamp-dwelling giant-like monsters, similar to the Old Norse-Icelandic þurs “giant” which also appears in Old English literature [þyrs]. In the Old English poem Beowulf, the Grendelkin have traditionally been identified as trolls by modern critics, and Grendel is himself described as a þyrs “swamp giant” by Beowulf (426). We learn from the Old English Maxims II that a þyrs is a lurking swamp creature: þyrs sceal on fenne gewunian/ ana innan lande “a giant shall dwell in a fen, alone within the land” (42-43).

This description aligns directly with descriptions of Grendel, who sinnihte heold/ mistige moras “ruled the misty marshes in the perpetual night” (161-62) as angenga “a lone-wanderer” (449). Indeed the monster is characterized as a þyrs when the narrator first names him: Wæs se grimma gæst Grendel haten,/ mære mearcstapa, se þe moras heold,/ fen ond fæsten; fifelcynnes eard “The grim ghast was called Grendel, the famous mark-stepper, he who ruled the marshes, the fens and strongholds, the realm of monsterkind” (102-04).

The Grendelkin are named giants elsewhere in Beowulf, marked with Old English terms such as eoten (112, 761, 1558, 1679), a relative cognate with the Old Norse jǫtunn [Icelandic jötunn] “giant” (commonly featured in Old Norse-Icelandic poetry and sagas), and the anglicized gigant “giant” (113, 1562, 1690), derived from the Latin gigans “giant” (notably used in the Latin Vulgate Bible (Genesis 6:4, Numbers 13:30–33, Deuteronomy 3:11, 2 Samuel 21:19). Despite the more than one hundred varying descriptions of Grendel and his mother, these Beowulf-monsters are undoubtedly giant in stature.

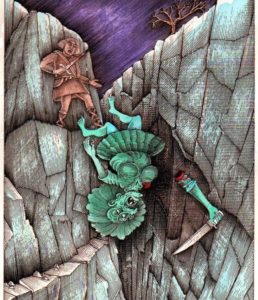

In the medieval tradition, the troll [Old Norse trǫll, Icelandic tröll, Middle High German trolle] is a creature from Scandinavian myth and legend which features prominently in eddiac poetry and saga literature. Grettis saga, one of the sagas which most famously contains trolls, including both the þurs (two references) and trǫll (twelve references). There are multiple references to trolls as nocturnal predators (ch. 16 & 33) and a general menace (ch. 57 & 64). After Grettir encounters and outwits a þurs “giant” called Þorir (ch. 61-62), he later turns his attention toward slaying a family of trolls (ch. 64-66). In Grettis saga, the trǫllkona mikil “great troll-woman” (also simply called trǫll) attacks the hall first prompting Grettir to hunt her down in her cave (ch. 65).

It is only when Grettir ventures deeper into their troll-den that he encounters a jǫtunn, who is of course her troll companion, but never explicitly named such (ch. 66). The giant-troll family that Grettir slays looms largest in the modern imagination. However, even here the categorical ambiguity between jǫtunn and trǫll highlights something fundamental about trolls in the Old Norse-Icelandic saga tradition. The range of monstrous creatures to which trǫll can apply is vast, and Sandra Alvarez notes that trǫll “could also be used to describe troublesome people, animals and even giants” in her blog “Trolls in the Middle Ages.” In Grettis saga, the term trǫll refers to the cave-dwelling monsters threatening the hall of Sandhaug and the human society within (ch. 64), but Grettir himself is earlier mistaken for a trǫll (ch. 33).

Moreover, in addition to trǫll referring to giant, the term can also indicate a witch, sorcerer, conjurer or any magic-user. Two Old Norse-Icelandic words for witchcraft, trǫlldómr and trǫllskap attest to the longstanding association between trǫll and magic. Moreover, in Hrólfs saga kraka the cowardly Hǫttr describes a flying monster, something akin to a dragon, as mesta trǫll “greatest troll” (ch. 35), and this creature terrorizes Hrólfr’s realm until Bǫðvar Bjarki slays the beast. Considering the semantic range for trǫll, the term appears to broadly refer to creatures monstrous, magical or both in the Old Norse-Icelandic literature.

Trolls can be giants. Trolls can be dragons. Trolls can be witches and warlocks. Above all, trolls are monsters. Despite this semantic ambiguity, each iteration of trǫll in Old Norse-Icelandic sagas emphasizes one major commonality—the wonder and monstrosity associated with anything or anyone deemed a troll in the extant literature from medieval Scandinavia.

Return in a few weeks for further discussion of the evolution of trǫll in modern English, specifically in the context of the online monsters commonly known as internet trolls.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English (2020)

University of Notre Dame

Texts & Translations

Byock, Jesse. Grettir’s Saga. Oxford University Press (2009).

—. The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki. Penguins Classics (1999).

Grimm, Jakob, and Wilhelm Grimm. Grimm’s Household Tales, translation by Margaret Hunt (1884).

Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. W. W. Norton & Company (2001).

Hostetter, Aaron K. Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry Project. Rutgers University (2007).

Kiernan, Kevin. The Electronic Beowulf. University of Kentucky (2015).

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. Allen & Unwin (1937).

Treharne, Elaine, and Jean Abbot. Beowulf By All. Stanford University (2016).

Þórðarson, Sveinbjörn. Icelandic Saga Database (2007).

Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Bloomsbury (1997).

Further Reading

Alvarez, Sandra. “Trolls in the Middle Ages.” Medievalist.net (2015).

Fahey, Richard. “Mearcstapan: Monsters Across the Border.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2018).

Firth, Matt. “Monsters and the Monstrous in the Sagas – the Saga of Grettir the Strong.” The Postgrad Chronicles (2017).

Fjalldal, Magnús. “Beowulf and the Old Norse Two-Troll Analogues.” Neophilologus 97 (2013): 541–553.

Jakobsson, Ármann. The Troll Inside You: Paranormal Activity in the Medieval North. Punctum Books (2017).

Lindow, John. Trolls: An Unnatural History. Reaktion Books (2015).

Shippey, Thomas A. The Shadow-Walkers : Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous. Brepols (2005).