Christmas is the most wonderful time of the year, but between treacherous weather, family politics, and dietary decisions, it can also be a tricky time to navigate. To help you get through the season, here are some top tips from the Old Norse sagas on surviving the holidays.

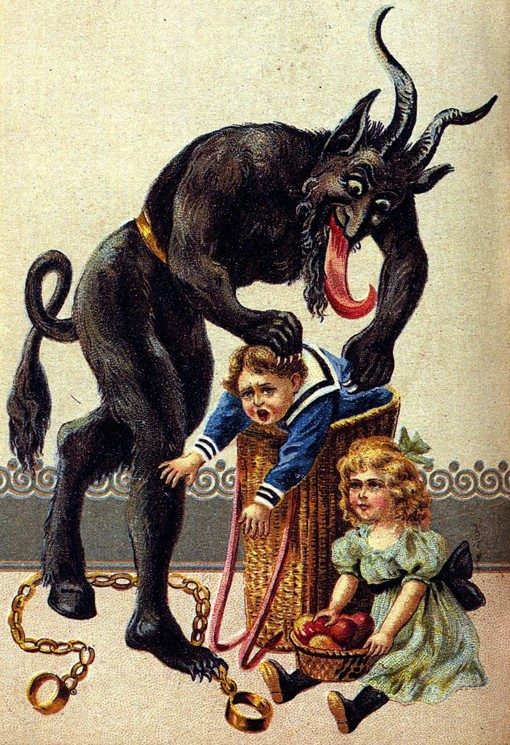

Drinking with the Devil. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, AM 673 a III 4to (Teiknibók), 18v. Image from handrit.is

Pick the right day to celebrate

If you lived in the Middle Ages, deciding when to host your winter festivities could be tricky. For a long time, as Scandinavia gradually converted to Christianity, the winter months saw the coexistence of two different Yule festivals: Christian Christmas and pagan Jól. The latter was likely celebrated differently across the region but said in one king’s saga, Hákonar saga góða, to begin on midwinter night and continue for three nights. These diverging celebrations became a point of friction during the conversion process so, around the middle of the tenth century, the Christian Norwegian king, Hákon the Good, attempted to consolidate the two. According to his saga, he decreed that ‘observance of Yule should begin at the same time as Christian people observed Christmas’ (97).

Although not without its challenges, this was a clever move. We can see its legacy several decades later in Óláfs saga helga, which describes the changing customs of a man named Sigurðr:

During the pagan period, he was accustomed to hold three sacrificial banquets every year, one at the winter nights, the second at midwinter, the third in the summer. And when he accepted Christianity, he still kept up his established custom with the banquets. Then, in the autumn he held a great party for his friends, and also a Yule feast in the winter and then again invited many people; a third banquet he held at Easter. (127)

Once you’ve settled on a date to celebrate, make sure you invite the right people – and if you get an invitation to someone else’s Yule-feast, it’s bad form to not show up. Some time after Sigurðr’s death, his brother Þórir invited his son Ásbjǫrn to a Yule feast, but Ásbjǫrn refused the invitation. Þórir took this as a personal slight and in return made such great mockery of Ásbjǫrn and his expeditions that Ásbjǫrn sullenly ‘stayed at home during the winter and went to no parties’ (131). A sad fate indeed.

Choose the perfect gifts

To be a powerful king in medieval Scandinavia, you had to surround yourself with groups of loyal retainers who would feast with you, fight for you, and uphold your rules. This loyalty needed to be rewarded, and Yule was the perfect time for kings and other powerful men to shower their best retainers with gifts. There’s even a term for gifts given in this season: ‘jólagjǫf’. In Óláfs saga helga, for instance, it is said that the king had a custom of ‘making great preparations, […] gathering together his treasures to give friendly gifts on the eighth evening of Yule’ (199). One of these gifts was a beautiful gold-adorned sword, given to his skald Sigvatr. This was said to be a fine, enviable treasure, though perhaps not as enviable as Óláfr’s earlier gift to Brynjólfr, which he received with a rather unimaginative verse:

Bragningr gaf mér

brand ok Vettaland.

The ruler gave me a sword and Vettaland (an important estate). (51)

Yule-gifts were also an important way to cement friendships and alliances in Scandinavian and Icelandic society, for which clothes appear to have been a popular choice. According to Laxdæla saga, King Haraldr Fairhair once gifted Óláfr Peacock ‘an entire suit of clothes made from scarlet’ (30). Even more impressive is a set of Yule-gifts exchanged between the Norwegian Arinbjǫrn and the Icelander Egill in Egils saga:

As a customary Yuletide gift, [Arinbjorn] gave Egil a silk gown with ornate gold embroidery and gold buttons all the way down, which was cut especially to fit Egil’s frame. He also gave him a complete set of clothes, cut from English cloth in many colours. Arinbjorn gave all manner of tokens of friendship at Yuletide to the people who visited him, since he was exceptionally generous and firm of character. (134)

Of course, before you splash out on expensive swords or clothes, you need to make sure the receiver is worthy of your gift. This is what King Raknarr did on the eve before Yule in the semi-legendary Bárðar saga snæfellsáss, entering the hall of King Óláfr Tryggvason, decked out with armour, helmet, sword, gold necklace, and gold ring. After going round the room to no response, he finally announces scathingly: “Here have I come and nothing at all has been offered to me by this great figure. I shall be more generous for I shall offer to award those treasures that I have here now to that man who dares to take them from me — but there is no one like that here.” (261)

Raknarr’s passive aggressive gifting strategy may not be the best example to follow, particularly as he turns out to be a reanimated corpse who must be slain by the hero Gestr. Instead, why not take inspiration from the troll-woman Hít in the same saga (254), whose Yule party favor for Gestr is a wonderfully loyal dog!

Feast and be merry!

Once you’ve bought and wrapped your presents, the next step is to plan your menu. The sagas are full of Yule feasts, although they rarely provide specific details of what is actually eaten. At one point in Eiríks saga rauða, for example, Eiríkr is hosting a number of voyagers over the winter at his home in Greenland, but starts to become gloomy as Yule approaches for he does not have the resources to throw them all a proper holiday feast. One of the voyagers, Karlsefni, comes to his rescue, offering him use of their provisions:

“[...] We’ve malt and flour and grain aboard our ships, and you may help yourself to them as you will, to prepare a feast worthy of your generous hospitality.”

Eirik accepted this. Preparations for a Yule feast began, which proved to be so bountiful that men could scarcely recall having seen its like. (11)

What exactly was in that grand feast goes entirely unstated, but it clearly involved some kind of malt, flour, and grain.Hákonar saga góða does suggest that horse meat was an important part of pagan Yule and other feasts. One winter, the saga relates, King Hákon attended a Yule feast with a large number of farmers from Þrándheimr, where he was very reluctantly forced to eat a few pieces of horse-liver and ‘drank all the toasts that the farmers poured for him without the sign of the Cross’ (102). It’s never good to offend your hosts — especially when they are armed.

One way to get into the sacred spirit of Christmas in advance of the gluttony to come is to fast in preparation. Indeed, not doing so could have dire consequences. In Grettis saga, the ill-tempered Glámr demanded meat from his wife on the eve of Yule. She tried to dissuade him, saying, “It’s not the Christian custom to eat on this day, because tomorrow is the first day of Christmas. It is our duty to fast today.” (101) Glámr scoffed at this, claiming a preference for the old pagan ways, and tucked into his meat. That very night, he was found dead in the snow and, even worse, eventually rose again to haunt the area.

As Christianity became the dominant religion in Scandinavia, later kings were less accepting of the old customs. One winter, King Óláfr the Holy got word that the farmers of Innþrœndir had been holding forbidden midwinter sacrificial feasts, and summoned a representative to explain themselves. But the quick-thinking man had the perfect excuse:

“We held,” he says, “Yule banquets and in many places in the districts drinking parties. The farmers do not make such scant provision for their Yule banquets that there is not a lot left over, and that was what they were drinking, lord, for a long time afterwards. At Mærin there is a large centre and huge buildings, and extensive settlements round about. People find it good to drink together there for enjoyment in large numbers.” (117)

The king remained suspicious, but could not fault the farmer’s logic. For, if there’s one thing about Christmas that everyone can agree on, it’s the importance of alcohol.

Drink… but not too much

When King Hákon the Good ordered the convergence of Yule and Christmas, he had one condition of how to celebrate: each person was to consume a measure of ale (16.2 litres, according to one estimate) and celebrate for as long as the ale lasted, or else pay a fine (97).

Drinking is a key component of most Yule feasts described across the sagas. Even core principles like seeking vengeance for fallen kin must come second. In Hákonar saga herðibreiðs, for instance, King Ingi relates that he told one man about the killing of another, sure that he would be spurred to vengeance, but ‘those people behaved as if nothing was as important as that Yule drinking feast and it could not be interrupted’ (227).

In fact, throughout the sagas, Yule-drinking (‘jóla-drykkja’) causes all sorts of problems. According to Óláfs saga helga, a Yule drinking competition in Jamtaland naturally led to bickering between Norwegians and Swedes, and the spilling of secrets as ‘the ale spoke through the Jamtr’ (172). In Eyrbyygja saga, Þórólfr bægifótr got his thralls drunk at Yule and convinced them to burn down an enemy’s house (168–69). The troll-woman’s Yule-feast in Bárðar saga Snæfellsáss steadily deteriorated as the drinking got heavier, leading to a rowdy game, a bloody nose, and a long feud (253).

Even without alcohol, Yule became a time of battle and slaughter throughout the sagas of kings. It is only in Magnúss saga blinda ok Haralds gilla that the two titular warring kings accepted a Christmas truce ‘because of the sanctity of the time’, although Magnúss did use this opportunity to fortify his town and ‘no more than three days over Yule were kept sacred so that no work was done’ (175).

This is a good example for academics everywhere: as much as we might feel the need to work over the holidays, there comes a time to put down our books, buy some gifts, and feast with family, friends, and nemeses — even if it is for just three days over Yule. If you manage to do so, you might just make it through the season alive.

Ashley Castelino, DPhil

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute, University of Notre Dame

Bibliography

Bard’s Saga [Bárðar saga snæfellsáss]. Translated by Sarah M. Anderson. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 2. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

Egil’s Saga [Egils saga]. Translated by Bernard Scudder. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 1. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

Erik the Red’s Saga [Eiríks saga rauða]. Translated by Keneva Kunz. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 1. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

The Saga of Grettir the Strong [Grettis saga]. Translated by Bernard Scudder. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 2. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

The Saga of the People of Eyri [Eyrbyggja saga]. Translated by Judy Quinn. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 5. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

The Saga of the People of Laxardal [Laxdæla saga]. Translated by Keneva Kunz. In The Complete Sagas of Icelanders, edited by Viðar Hreinsson. Vol. 5. Leifur Eiríksson, 1997.

Snorri Sturluson. Hákonar saga góða. In Heimskringla, translated by Alison Finlay and Anthony Faulkes. Vol. 1. Viking Society for Northern Research, 2011.

Snorri Sturluson. Hákonar saga herðibreiðs. In Heimskringla, translated by Alison Finlay and Anthony Faulkes. Vol. 3. Viking Society for Northern Research, 2015.

Snorri Sturluson. Óláfs saga helga. In Heimskringla, translated by Alison Finlay and Anthony Faulkes. Vol. 2. Viking Society for Northern Research, 2014.