[This post, part of an effort to merge our undergraduate and graduate blogs, was written in response to an essay prompt for Kathryn Kerby-Fulton's undergraduate course on "Chaucer's Biggest Rivals: The Alliterative Poets." It comes from the former "Medieval Undergraduate Research" website.]

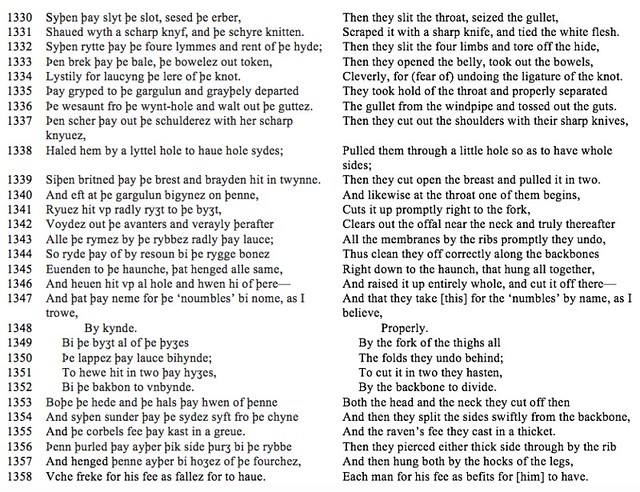

The medieval epic poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Gawain) offers a number of plots and subplots designed to garner the interest of the poet’s 14th century English audience. Yet, while such medieval happenings may have kept Gawain’s original audiences on the edge of their seats, the average 21st century student of literature is likely far less familiar with or interested in the ritual demands of courtly life. One such example of this disconnect can be found in lines 1330-1358 of Gawain, where the poet provides a thoroughly descriptive account of the ritualistic butchering of slaughtered deer, an important symbol of sophistication and skill for a medieval audience. In an attempt to appeal to modern readers, Marie Borroff’s translation of this passage focuses less on its original physicality and detail and fixates more singularly on recreating a medieval poetic style.

The Gawain-poet employs alliteration, an essential element of medieval English poetry, frequently throughout this passage, but Borroff’s attempts to insert it into her translation often sacrifice the detailed imagery of the original poem. The first line of this passage (line 1330), reads “Syþen þay slyt þe slot,” which translates literally to “Then they slit the hollow at the base of the throat.” Borroff translates the line as “Then they slit the slot open.” Borroff’s word choice maintains the “sl” and hard “t” sounds, the slit/slot word play, and the “s” alliteration of the original poem, all important elements of the line. However, her translation also ignores the more accurate details of the poet’s account. “Slot,” unlike “throat,” is ambiguous in this context, giving the reader no real, concrete notion of the first step in the flaying ritual. Borroff makes a similar decision in line 1331, where she translates “Schaued wyth a scharp knife, and þe schyre knitten” (“Scraped with a sharp knife, and tied the white flesh”) as “Trimmed it with trencher-knives and tied it up tight.” Like the original, the translation alliterates in this line. However, Borroff’s alliteration seems forced and makes the line sound more like a nursery rhyme than an exhibition of skilled butchery.

Borroff’s translation of line 1331 is significant for another reason as well. She opts not to translate “schyre,” or “white flesh,” so as to allow her to more easily maintain alliteration in the line. This word, however, hearkens back to an important passage earlier in the poem, in which Gawain beheads the Green Knight. In this earlier passage, the word “schyire” (an alternative form of “schyre,” line 425) describes the bare neck of the Green Knight into which Gawain drives the axe. This word repetition draws a key parallel between Bertilak (the lead figure of this hunt) and the Green Knight, important foreshadowing for the later revelation that the two are the same person. “Schyre” appears once more in line 2313 of the poem in order to describe the “white flesh” of Gawain’s neck as it is struck by the Green Knight’s axe. The use of this word in all three of these contexts highlights the gaming nature of the three situations, drawing a near-comedic link between the entertainment purposes of the beheading scenes and the hunt. It also links all three events to the great test of Gawain’s character that frames the poem. By neglecting “schyre” entirely, Borroff excludes these important connections in the poem. However, her translation does faithfully carry over some of the other words shared by the three scenes, such as “sharp” (“scharp”), dividing or cutting (“schyndered,” “sunder,” “seuered”), head (“hede”), neck (“halce”), and others.

Borroff also attempts to convey the medieval background of the poem by employing intentionally archaic language. In the passage, she translates the word “wesaunt” (which means “gullet”) as “weasand” (1336), “chyne” (“backbone”) as “chine” (1354), and “corbeles fee” (“raven’s fee”) as “Corbie’s bone” (1355). The choice of “chine” is especially questionable, as Borroff could have selected “spine” and both expanded her chosen alliteration and conveyed the line’s meaning more clearly. To Borroff’s credit, however, the poem’s original terminology in these cases may have been rather archaic for medieval audiences as well. Both “chyne” and “corbeles fee” come from Old French, and while “wesaunt” comes from Old English, it exhibits a notable French influence. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, French became the language of the English aristocracy, and the use of archaic French terms in this passage hints at the elite standing and high education of the poet’s intended audience. Thus, this passage raises important questions regarding the role of the translator. Should Borroff have chosen clear, more easily understandable synonyms in her translation? Or was she correct in maintaining the original, elitist vocabulary of the original passage, entirely understandable only to those intimately familiar with hunting culture?

One area in which Borroff’s translation of this passage succeeds is in her treatment of the bob and wheel in lines 1348-1352. In Gawain, the bob and wheel form the final five lines of each stanza, obey a strict ababa rhyme scheme, and often relay the major events of the poem. These lines in the original poem are masterfully lyrical through a successful combination of end rhyme, internal rhyme, alliteration, and rhythm. Although her translation does not fully capture this lyricism, Borroff provides a relatively faithful translation of these lines and captures the rhyme scheme very well. Furthermore, she abandons the strict attention to alliteration that she displays in the rest of the passage, focusing more intently on the imagery and rhyme of the lines. This shift in focus from strictly medieval styles and language to a faithful depiction of minute details allows Borroff to accurately portray the lyrical impact of these lines in the original poem.

Although Borroff’s translation seems to make only minor alterations to the original Gawain poem, her choices reflect a difference in focus between a medieval audience and the modern reader. In particular, her translation of lines 1330-1358 attempts to convey the “feel” of medieval poetry by fixating on alliteration and archaic language. However, this sacrifices the detailed imagery of the flaying scene, an important and entertaining ritual in medieval courts. By excising these details, Borroff’s translation removes some of the thrill of the hunt for modern audiences.

Casey O’Donnell

University of Notre Dame

References

Borroff, Marie. The Gawain Poet : Complete Works : Patience, Cleanness, Pearl, Saint Erkenwald, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2011. Print.

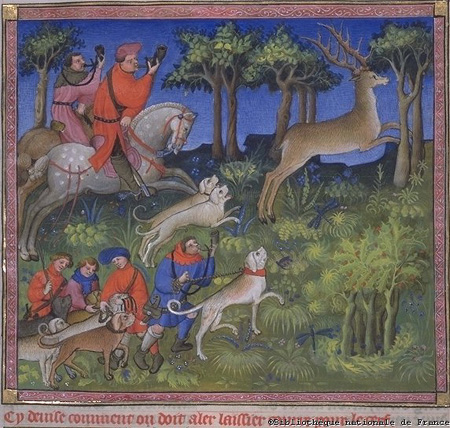

Hunting the Roebuck, Gaston Phoebus, Le Livre de la chasse, in French, France, Paris, ca. 1407, The Morgan Library & Museum; MS M.1044 (fol. 64). Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983. Image courtesy of Faksimile Verlag Luzern.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Eds. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. Oxford University Press, 1968. Print.

The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript. Eds. Malcolm Andrew and Ronald Waldron. Liverpool University Press, 2007. Print.

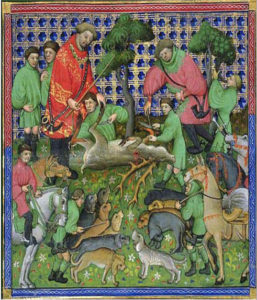

Undoing and Breaking Up a Hart, Gaston Phoebus, Le Livre de la chasse, in French, France, Paris, ca. 1407, The Morgan Library & Museum; MS M.1044 (fol. 64). Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983. Image courtesy of Faksimile Verlag Luzern.