It is always daunting to start research in a new location; it is perhaps more so when you are one of the first people (if not the first) from your institution to arrive there and the advice you have to go on is whatever one can glean off of a library website, if that even exists. The aim of this post is to provide information about conducting research at the National Library of the Kingdom of Morocco, from getting a researcher card and gaining access to the collection to requesting manuscripts and getting digital copies for future use as well as other information about library services.

Getting there and Gaining Access

The Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc (henceforth BNRM) is the new name for what used to be the Bibliothèque General. Founded in 1924 and renamed in 2003

Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc, the library now occupies a beautiful new building on Avenue Ibn Khaldoun in the Agdal neighborhood of Rabat, Morocco. Easily accessible by car and by the Rabat Tram (Station: Bibliothèque Nationale), it is also a 30 minute walk from the neighborhoods of L’Océan and Hassan and a 15 minute walk from the Rabat Ville Train Station.

The BNRM is open M-F 9:00-21:00 and Saturday 9:00 – 18:00, with reduced hours during the month of Ramadan (M-F 9:00 -15:00). The four main sections of the library are the Espace Grand Public, Espace cherchéres, Espace collections spécialisées, and Espaces audiovisuals et malvoyants. There is also an auditorium on the ground floor, a public lobby where artwork and various cultural installations reside, as well as a café with an outdoor terrace on the second level. At the end of the lobby on the left there is the bag check, bathroom, and the Inscription (Registration) office. Requests can be done in French or in Moroccan Arabic. For those who speak only Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) your interactions will be a bit more limited; be prepared to have staff, especially those working at the security level, to reply only in Moroccan Arabic to your MSA.

In order to gain access to the library, one needs to complete and print the Inscription form provided on the BNRM Website BNRM Website, then bring that, a copy of your passport, proof of University affiliation and/or your Letter D’Attestation (in French or Arabic) stating your research, and 150 MAD to the Inscription office. If you can’t print your Inscription form —the system does not like to work with Mac OS— bring everything else with you when you go and tell them your situation; usually people are forgiving and will print everything there. Once you have given them your paperwork and paid the fee (if they are nice, you might only get charged 100 MAD), they will print your library card. The card is valid for one year and can be renewed by completing the same process outlined above. Unlike other libraries, such as the Biblioteca Nacional de España, you do not have to register your computer or electronic devices with the BNRM.

The Library Itself

Bags, purses, folders, and laptop cases are not allowed in the BNRM; they must be checked at the bag check. However, you are allowed to bring your laptop, your phone, a small bottle of water, pens, pencils, and notebooks. Once you’ve checked your bag at the bag check, you enter the library by going through the main turnstile. Tap your library card on the card reader to pass through.

The Espace Grand Public is down the hallway on your right. A large, 2 story reading room with open stacks access to a number of books, the majority in Arabic but a sizable minority of French publications with other European languages thrown into the mix, the Espace Grand Public is a popular space for university students to study. The books are catalogued according to the Dewy Decimal System though shelving can get a bit creative within the sections themselves. At the far end of the Espace Grand Public is a copy room where you can request photocopies of books for a small fee. Usually a couple of pages costs 1 Moroccan dirham (MAD), approximately 10¢, whereas 50 pages will cost around 25 MAD (approximately $2.50). At present, there are two scanners in the Espace Grand Public but they are not operational.

NB: One cannot request an entire copy of a book; for that, best to download a scanner app to a tablet or phone and make a scan using the camera.

The Espace Cherchères is a separate area towards the back of the library on the right; to gain access to the EC, you again pass through a turnstile. If your card does not let you pass, go back to Inscriptions and report the problem. Inside the EC there are several large tables with outlets on the first and second floors, additional reference books, microfilm readers, computers for searching the library catalog, and the request desk.

Catalogs and Websites

The website for the BRNM is in French and Modern Standard Arabic but the majority of the catalog holdings are in Arabic. This can be a bit frustrating if you are working off of Latin transcriptions of Arabic titles but you can always give the title to one of the librarians and they can look it up for you. Alternatively, you can also find the item via Latin transcription on World Cat and then click on the link to the Bibliothèque Nationale to get the call number.

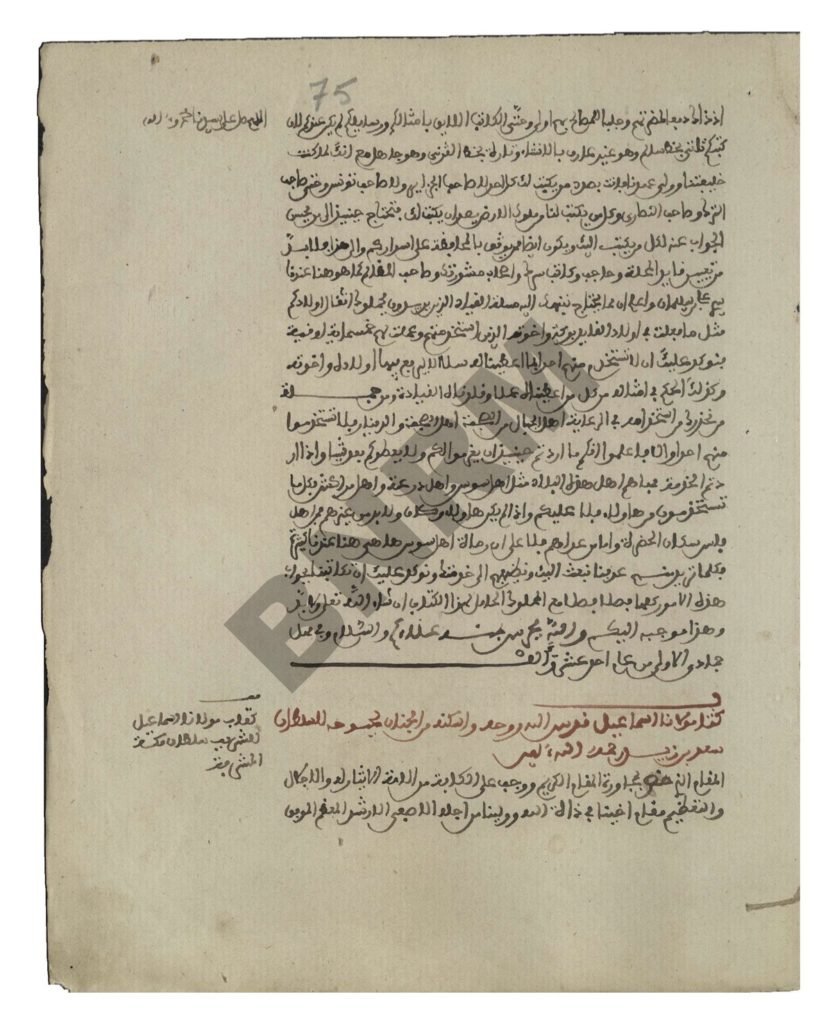

For manuscripts, one must search on the BNRM website in Arabic search on the BNRM website in Arabic or download one of the manuscript catalogs to look up the call number. The catalogs are a good place to start if you want to browse but in order to find a specific manuscript, it is best to just go directly to the online catalog.

NB: For those who are following references pre 2003, note that letters associated with manuscripts are now using the Arabic rather than the Latin alphabet. Thus MS 419 G becomes MS 419 ج , K becomes ك and N becomes ن

Requesting Manuscripts

To request a microfilm, fill out the request form at the request desk in either French and Arabic, complete with the shelf number. Once you put in your request, the librarian will fetch the microfilm and set it up on one of the viewers.

The viewers are not the greatest for actually working off of the manuscripts so it is best to find what you need within the manuscript, noting the page numbers and then put in a request for a digital copy at the request desk. In order to complete this request you will need another copy of your passport page and your Lettre d’Attestation, as well as additional money. The librarian will write out two copies of your request, then ask you for your name, contact information including email address and/or phone number, and whether or not you want the scan emailed to you or on a disk. You will also need to sign both copies of the form, then take one of them to an administrative office on the other side of the library; it is at that office where you will pay for the copy. For the record, 10 manuscript folios cost 20 MAD ($2). After paying, take your receipt back to the Request Desk in Espace Cherchères and give it to the librarian. Your digital copy will be ready in a day or two.

Final Notes

The BRNM is a popular spot for university students since they can get access at a reduced rate; expect the place to get crowded in the afternoon and into the evening come the end of term (usually January and July). Only upper level students, however, can gain access to the Espace Cherchères.

Water bottles are allowed but you must keep your water bottle on the floor by your chair, not on the table. A guard (speaking Moroccan Darija) will come by and remind you if you forget, even if the bottle is empty. Also, don’t bring water with you during Ramadan if you can help it.

There are two bathrooms, one on the ground floor and one on the upper floor, but you need to go out through the turnstile to get to them. They are very clean but notoriously lacking in toilet paper; keep a pack of tissues with you. The upstairs toilets also have places to wash for ritual prayer and to fill up your water bottle.

The cafe does breakfast lunch and dinner for about 30-50 MAD ($3-5) depending upon what you order. The coffee and tea is a bit overpriced for what you’re getting but the food is solid. It is also a popular place for students as you do not need to have a library card to enter the area. The cafe is closed during Ramadan.

There is Wi-Fi but it is slow; if you’re working off of the cloud or just trying to open your email on your laptop you will get frustrated. Consider adding internet credit to your local phone and tethering your laptop to it order to work with minimal disruptions.

Additional Resources